Authored by Michael Lebowitz via RealInvestmentAdvice.com,

Having discussed the Federal Reserve’s trolley car problem in Part One, it’s time to cross the travel abroad to see how similar issues are playing out in Japan and Europe.

Japan’s Trolley Car Problem

Kuroda Haruhiko and the Bank of Japan (BOJ)

Japan’s inflation is rising quickly; however, monthly, and annual levels are well below those in Europe or America. However, their reprieve from back-breaking inflation may not be long-lived. This is especially true if BOJ Governor Kuroda continues to employ an extremely easy monetary policy.

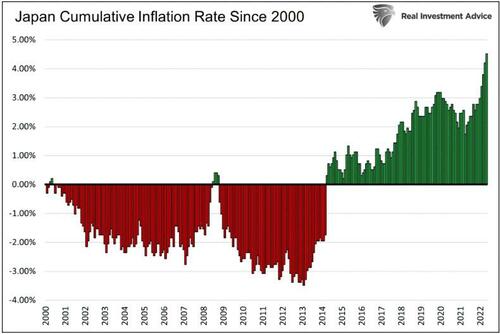

The graph below shows that cumulative inflation since 2000 was negative until 2014. Since then, it has perked up and, in the last year, has taken another leap higher.

Kuroda is taking the opposite tack as the Fed. Inflation is public enemy number one for the Fed. Despite inflation rising in Japan, albeit not as high as in the U.S., Kuroda remains committed to keeping borrowing costs down at all costs. Below are a few recent quotes from Kuroda.

-

We won’t hesitate to ease monetary policy further if necessary.

-

There is no limit to yield curve control (QE)

-

No change to the idea that yield curve control strongly supports economic recovery

-

Recent rapid yen weakening is negative for the economy.

Japan’s Rubber Band

In part one of this article, we described the rubber band theory to help better grasp burgeoning debt loads. In the case of the United States, the debt cycle rubber band is nearly fully stretched. The Japanese rubber band, in comparison, is stretched beyond what many think is possible.

For more background on Japan’s problems, Liquidity Crisis in the Making Parts One and Two detail how Japan got into its current mess and why investors worldwide should care.

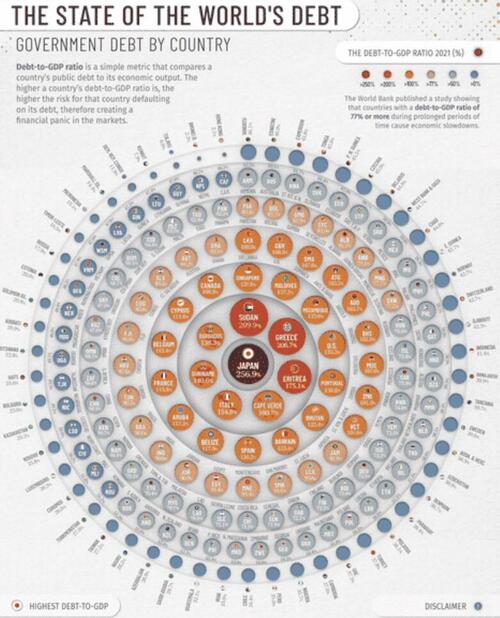

The graphic below shows Japan’s debt to GDP ratio is about 255%, almost twice that of the United States and above all Europe’s nations as well.

To allow for such debt expansion, Japan has presided over the world’s easiest monetary policies regarding interest rates and QE.

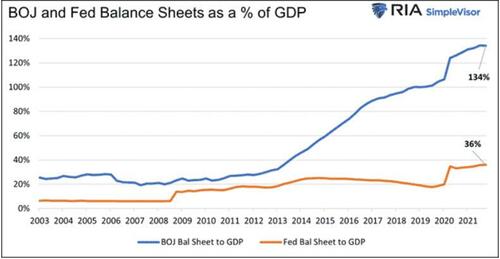

As a percentage of GDP, the BOJ balance sheet has grown to over 4x the size of the Fed’s.

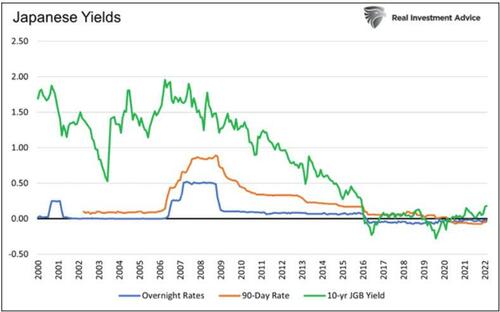

Interest rates in Japan are meager at best and have been negative for the better part of the last five years.

Such an easy monetary policy has kept Japan solvent. Japan may have delayed its day of reckoning, but it has not canceled it. This ongoing strategy makes Japan increasingly overleveraged and reliant on negative interest rates. Marginal upticks in yields are detrimental to Japan’s financial health.

Testing the BOJ’s resolve

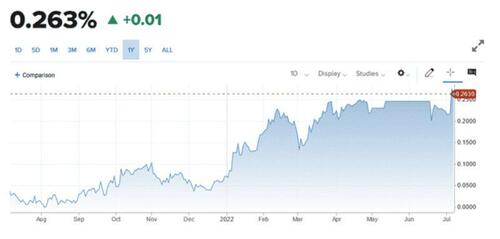

Global and local inflationary concerns recently put upward pressure on Japanese bond yields. The graph below shows the Japanese ten-year bond is bumping up against .25% after being stuck around 0% throughout 2021.

Unlike the Fed, which allows rates to increase, Japan’s uber dependency on low yields forces them to stymie rising yields.

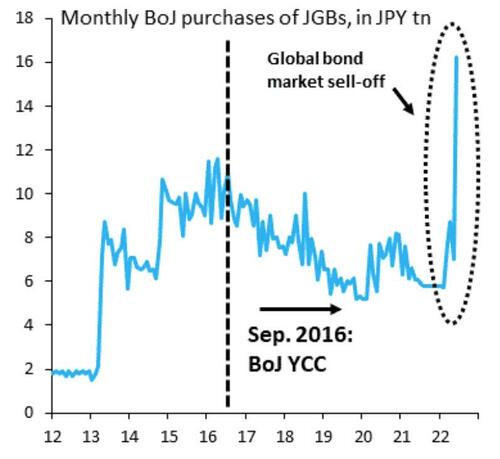

The BOJ is keeping its Fed Funds equivalent rate negative and aggressively capping the yield of its ten-year note at 0.25% with substantial QE. In June 2022, as the 10-year note hit 0.25%, they bought more bonds than any other month in the last ten years. As inflation increases and short-sellers smell opportunity, the pressure on the BOJ will increase. Its resolve will likely be tested in spades in the coming months.

Consequences of Resolve

One important consequence of the BOJ’s single-minded policy is that it is crushing its currency. A weaker yen further stokes inflationary pressures. The yen, as shown below, is now at 20-year lows, having fallen over 15% in just the last three months.

Their dilemma is summarized neatly in a piece we wrote in May 2022- Japanese Inflation Part 2.

“However, as the BOJ tries to stop rates from rising, they weaken the yen. Japan is in a trap. They can protect interest rates or the yen but not both. Further, its actions are circular. As the yen depreciates, inflation increases, and the Japanese central bank must do even more QE to keep interest rates capped.” –

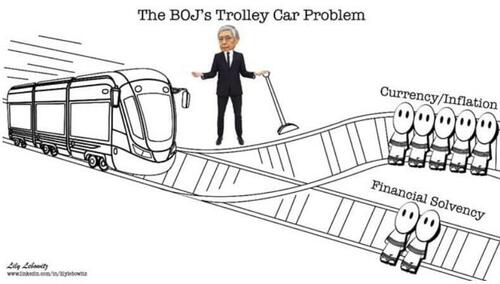

As the switchman at the BOJ trolley car track junction, Kuroda must decide between maintaining financial solvency via low-interest rates against the potential for a currency meltdown and much higher inflation rates.

Europe’s Trolley Car Problem

Christine Lagarde -European Central Bank (ECB)

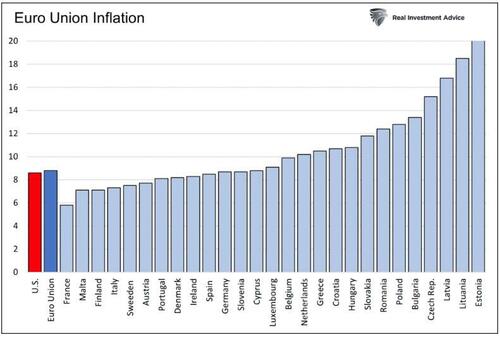

Europe’s trolley car problem is a hybrid of the U.S. and Japan’s issues. Like the U.S., the ECB fully acknowledges it has an inflation problem. However, like Japan, Europe is desperate to maintain low-interest rates to maintain some paltry level of economic growth and keep its nations solvent. Also, like Japan, the euro is plummeting versus the dollar, which further fuels inflationary pressures.

Thus far, the ECB seems to be following the Fed’s hawkish footsteps, but at a snail’s pace. The following quotes come from a Wall Street Journal article detailing ECB President Christine Lagarde’s latest speech.

-

Ms. Lagarde said Europe’s inflation problem was deepening but warned that the region also faced weaker growth prospects related to the war in Ukraine.

-

She said the ECB would increase its key rate by 0.25 percentage point next month, to minus 0.25%, and possibly by a larger amount in September.

-

The ECB’s gradualism, as Ms. Lagarde described its approach, reflects the larger economic blow that the war in Ukraine has dealt to Europe, which relies on Russian energy imports, and concerns about how higher borrowing costs will pressure fragile and highly indebted southern European economies such as Italy and Spain.

One Monetary Policy for All

The ECB is unique compared to the U.S. and Japan. They are not managing the needs of one country but many countries with individual economies and varying economic factors. As we have seen from the ECB, monetary policy tends to serve weaker nations rather than stronger ones.

In 2012, ECB President Mario Draghi famously said, “we will do whatever it takes to save the Euro and believe me it will be enough.”

Greece and Portugal faced crippling bond yields and high debt levels at the time. Bankruptcy was inevitable unless the ECB calmed investor fears.

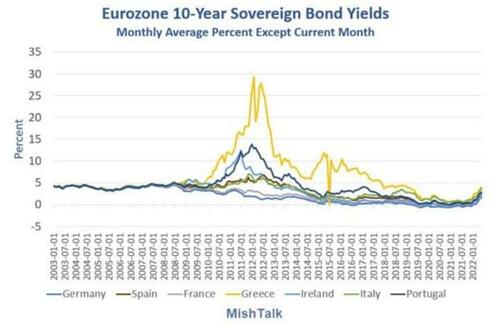

Draghi’s comment was a powerful message that the ECB would ensure that countries like Greece and Portugal do not fall victim to higher interest rates. As shown in the graph below from Mish Shedlock, the spreads or yield differentials between various Euro nations were extremely wide and tightened after his comments. Over the last few years, they have primarily traded in line. Investors no longer differentiate much between countries like Germany with solid financial backing and others with less-than-ideal financial strength.

Greece Again

Currently, yield spreads between countries with weaker economies and stronger ones are widening. For instance, Greece’s 10-year bond yield is now 220 bps greater than Germany’s. A year ago, the spread was under 100 bps. While the spread is not close to the harrowing levels in 2012, it is becoming a problem.

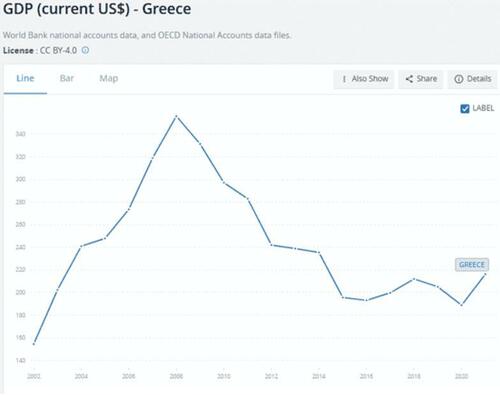

Greece is a zombie nation. They spot a Federal Debt to GDP ratio of over 200. Its economic growth is paltry at best. As shown below, its GDP is the same today as in 2014. Since 2017, its debt has grown by 12% and is expected to grow further in the coming years. How can a nation expand its debt while its ability to pay for it declines or stays flat? It can, but only with enormous monetary support from its central bank.

Euro in Freefall

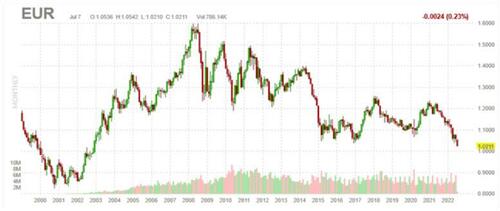

Making fighting inflation harder for the ECB, the euro is approaching 20-year lows. As in Japan’s case, a weaker euro is inflationary. Like Japan, the euro is weakening because currency traders think the ECB is not doing enough to arrest inflation. At the same time, the Fed is aggressively trying to stop inflation. Stock, bond, and currency traders fear inflation will worsen in the euro region, potentially resulting in higher interest rates, more inflation, and financial hardship for some nations.

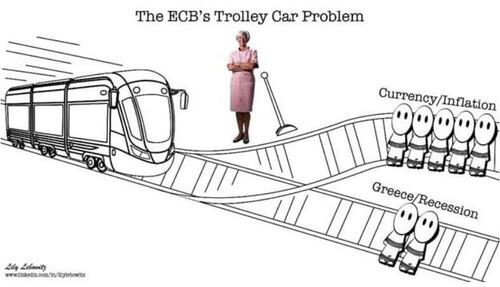

Lagarde’s Trolley Car Problem

As the switchman at the ECB trolley car track junction, Lagarde is choosing between high inflation and a currency meltdown versus the solvency of some of its nations and a recession.

Summary

While the situations in the U.S., Europe, and Japan are different, all three areas are paying the price for years of fiscal and monetary tomfoolery. Using monetary policy to ensure low-interest rates encouraged unproductive debt growth. As liabilities grew faster than GDP, their ability to service debt became harder without continually having to administer lower interest rates and more QE.

The U.S., Japan, and Europe bought time but only made their problems worse. It was just a matter of time before the consequences would rear their ugly head.

Inflation is the bugaboo that upset the game. Inflation and higher bond yields wreak havoc on countries overly dependent on debt.

The Fed understands the predicament best and aggressively fights inflation with higher rates and QT. Recent comments allude that they are willing to sacrifice jobs and a recession to lower inflation.

The ECB is dragging its feet. They are not only concerned with inflation but must also consider how tighter monetary policy affects the finances of its zombie nations.

The BOJ is not worried about inflation or its weakening currency. It is still forging ahead with an extremely easy monetary policy. If inflation rises to similar levels as the U.S. and Europe, the BOJ will pay dearly for its laissez-faire stance.

The risks for all three regions are clear and present. How it plays out has yet to be seen.

Authored by Michael Lebowitz via RealInvestmentAdvice.com,

Having discussed the Federal Reserve’s trolley car problem in Part One, it’s time to cross the travel abroad to see how similar issues are playing out in Japan and Europe.

Japan’s Trolley Car Problem

Kuroda Haruhiko and the Bank of Japan (BOJ)

Japan’s inflation is rising quickly; however, monthly, and annual levels are well below those in Europe or America. However, their reprieve from back-breaking inflation may not be long-lived. This is especially true if BOJ Governor Kuroda continues to employ an extremely easy monetary policy.

The graph below shows that cumulative inflation since 2000 was negative until 2014. Since then, it has perked up and, in the last year, has taken another leap higher.

Kuroda is taking the opposite tack as the Fed. Inflation is public enemy number one for the Fed. Despite inflation rising in Japan, albeit not as high as in the U.S., Kuroda remains committed to keeping borrowing costs down at all costs. Below are a few recent quotes from Kuroda.

-

We won’t hesitate to ease monetary policy further if necessary.

-

There is no limit to yield curve control (QE)

-

No change to the idea that yield curve control strongly supports economic recovery

-

Recent rapid yen weakening is negative for the economy.

Japan’s Rubber Band

In part one of this article, we described the rubber band theory to help better grasp burgeoning debt loads. In the case of the United States, the debt cycle rubber band is nearly fully stretched. The Japanese rubber band, in comparison, is stretched beyond what many think is possible.

For more background on Japan’s problems, Liquidity Crisis in the Making Parts One and Two detail how Japan got into its current mess and why investors worldwide should care.

The graphic below shows Japan’s debt to GDP ratio is about 255%, almost twice that of the United States and above all Europe’s nations as well.

To allow for such debt expansion, Japan has presided over the world’s easiest monetary policies regarding interest rates and QE.

As a percentage of GDP, the BOJ balance sheet has grown to over 4x the size of the Fed’s.

Interest rates in Japan are meager at best and have been negative for the better part of the last five years.

Such an easy monetary policy has kept Japan solvent. Japan may have delayed its day of reckoning, but it has not canceled it. This ongoing strategy makes Japan increasingly overleveraged and reliant on negative interest rates. Marginal upticks in yields are detrimental to Japan’s financial health.

Testing the BOJ’s resolve

Global and local inflationary concerns recently put upward pressure on Japanese bond yields. The graph below shows the Japanese ten-year bond is bumping up against .25% after being stuck around 0% throughout 2021.

Unlike the Fed, which allows rates to increase, Japan’s uber dependency on low yields forces them to stymie rising yields.

The BOJ is keeping its Fed Funds equivalent rate negative and aggressively capping the yield of its ten-year note at 0.25% with substantial QE. In June 2022, as the 10-year note hit 0.25%, they bought more bonds than any other month in the last ten years. As inflation increases and short-sellers smell opportunity, the pressure on the BOJ will increase. Its resolve will likely be tested in spades in the coming months.

Consequences of Resolve

One important consequence of the BOJ’s single-minded policy is that it is crushing its currency. A weaker yen further stokes inflationary pressures. The yen, as shown below, is now at 20-year lows, having fallen over 15% in just the last three months.

Their dilemma is summarized neatly in a piece we wrote in May 2022- Japanese Inflation Part 2.

“However, as the BOJ tries to stop rates from rising, they weaken the yen. Japan is in a trap. They can protect interest rates or the yen but not both. Further, its actions are circular. As the yen depreciates, inflation increases, and the Japanese central bank must do even more QE to keep interest rates capped.” –

As the switchman at the BOJ trolley car track junction, Kuroda must decide between maintaining financial solvency via low-interest rates against the potential for a currency meltdown and much higher inflation rates.

Europe’s Trolley Car Problem

Christine Lagarde -European Central Bank (ECB)

Europe’s trolley car problem is a hybrid of the U.S. and Japan’s issues. Like the U.S., the ECB fully acknowledges it has an inflation problem. However, like Japan, Europe is desperate to maintain low-interest rates to maintain some paltry level of economic growth and keep its nations solvent. Also, like Japan, the euro is plummeting versus the dollar, which further fuels inflationary pressures.

Thus far, the ECB seems to be following the Fed’s hawkish footsteps, but at a snail’s pace. The following quotes come from a Wall Street Journal article detailing ECB President Christine Lagarde’s latest speech.

-

Ms. Lagarde said Europe’s inflation problem was deepening but warned that the region also faced weaker growth prospects related to the war in Ukraine.

-

She said the ECB would increase its key rate by 0.25 percentage point next month, to minus 0.25%, and possibly by a larger amount in September.

-

The ECB’s gradualism, as Ms. Lagarde described its approach, reflects the larger economic blow that the war in Ukraine has dealt to Europe, which relies on Russian energy imports, and concerns about how higher borrowing costs will pressure fragile and highly indebted southern European economies such as Italy and Spain.

One Monetary Policy for All

The ECB is unique compared to the U.S. and Japan. They are not managing the needs of one country but many countries with individual economies and varying economic factors. As we have seen from the ECB, monetary policy tends to serve weaker nations rather than stronger ones.

In 2012, ECB President Mario Draghi famously said, “we will do whatever it takes to save the Euro and believe me it will be enough.”

Greece and Portugal faced crippling bond yields and high debt levels at the time. Bankruptcy was inevitable unless the ECB calmed investor fears.

Draghi’s comment was a powerful message that the ECB would ensure that countries like Greece and Portugal do not fall victim to higher interest rates. As shown in the graph below from Mish Shedlock, the spreads or yield differentials between various Euro nations were extremely wide and tightened after his comments. Over the last few years, they have primarily traded in line. Investors no longer differentiate much between countries like Germany with solid financial backing and others with less-than-ideal financial strength.

Greece Again

Currently, yield spreads between countries with weaker economies and stronger ones are widening. For instance, Greece’s 10-year bond yield is now 220 bps greater than Germany’s. A year ago, the spread was under 100 bps. While the spread is not close to the harrowing levels in 2012, it is becoming a problem.

Greece is a zombie nation. They spot a Federal Debt to GDP ratio of over 200. Its economic growth is paltry at best. As shown below, its GDP is the same today as in 2014. Since 2017, its debt has grown by 12% and is expected to grow further in the coming years. How can a nation expand its debt while its ability to pay for it declines or stays flat? It can, but only with enormous monetary support from its central bank.

Euro in Freefall

Making fighting inflation harder for the ECB, the euro is approaching 20-year lows. As in Japan’s case, a weaker euro is inflationary. Like Japan, the euro is weakening because currency traders think the ECB is not doing enough to arrest inflation. At the same time, the Fed is aggressively trying to stop inflation. Stock, bond, and currency traders fear inflation will worsen in the euro region, potentially resulting in higher interest rates, more inflation, and financial hardship for some nations.

Lagarde’s Trolley Car Problem

As the switchman at the ECB trolley car track junction, Lagarde is choosing between high inflation and a currency meltdown versus the solvency of some of its nations and a recession.

Summary

While the situations in the U.S., Europe, and Japan are different, all three areas are paying the price for years of fiscal and monetary tomfoolery. Using monetary policy to ensure low-interest rates encouraged unproductive debt growth. As liabilities grew faster than GDP, their ability to service debt became harder without continually having to administer lower interest rates and more QE.

The U.S., Japan, and Europe bought time but only made their problems worse. It was just a matter of time before the consequences would rear their ugly head.

Inflation is the bugaboo that upset the game. Inflation and higher bond yields wreak havoc on countries overly dependent on debt.

The Fed understands the predicament best and aggressively fights inflation with higher rates and QT. Recent comments allude that they are willing to sacrifice jobs and a recession to lower inflation.

The ECB is dragging its feet. They are not only concerned with inflation but must also consider how tighter monetary policy affects the finances of its zombie nations.

The BOJ is not worried about inflation or its weakening currency. It is still forging ahead with an extremely easy monetary policy. If inflation rises to similar levels as the U.S. and Europe, the BOJ will pay dearly for its laissez-faire stance.

The risks for all three regions are clear and present. How it plays out has yet to be seen.