Retired Supreme Court Justice Stephen Breyer recently lamented the “unfortunate” leak of the decision overturning Roe v. Wade, an incident that two years ago today threatened the very core of the institution he once represented.

“You try to avoid getting angry or that — you try in the job — you try to remain as calm, reasonable, and serious as possible. I think it was unfortunate,” he said of the leak of the draft decision in the Dobbs v. Jackson Women’s Health Organization case.

Justice Clarence Thomas called the leak a type of “infidelity” that “changes the institution fundamentally.” Chief Justice John Roberts directed the court’s marshal to launch an investigation into the leak, which months later ultimately turned up inconclusive.

Even two years later, there are signs that the high court may still be reeling from the unprecedented leak decision, according to legal experts and court watchers interviewed by the Washington Examiner.

“The court’s been incredibly slow at deciding cases, it’s been slow at taking new cases, I mean it’s just been slow across the board,” Jonathan Adler, a constitutional law professor at Case Western Reserve University, told the Washington Examiner. “It’s starting to look like a new normal, but I certainly hope it’s not the case. I’m someone who thinks the court should be taking more cases than it does.”

Experts who spoke to the Washington Examiner stressed that it is difficult to gauge whether the leak is still negatively affecting the high court today. After all, the Supreme Court has gone through other recent changes, such as altering its protocols during the 2020 pandemic — it now allows oral argument audio to be streamed for each case, for example — and in recent months, the high court has taken on more thorny political issues including lawsuits against the Biden administration’s COVID-19 vaccine mandate, President Joe Biden’s sweeping student loan forgiveness plan, and cases involving former President Donald Trump, to name a few.

“I don’t know that we have the information that allows us to isolate one variable as opposed to the others,” Adler said.

So far, the high court has only agreed to hear eight cases for the fall 2024-25 term, though they will likely accept 60 to 70 total before their list for the next term is full. This time last year, the justices had only confirmed eight cases to be weighed in the current term as well. Additionally, the court last year had only released five opinions by April 28, while the court this year has already decided 18 cases by the same date.

“One symptom of the Dobbs leak last term was the slow pace early on in the term,” Adam Feldman, the founder of the Empirical SCOTUS blog, which follows statistics about high court cases, told the Washington Examiner.

Last term, it took the justices until Jan. 23, 2023, four months after justices returned to the bench in October 2022, to issue their first opinion. Typically, the justices deliver their first opinion of the term by late November or sometime in December, but the wait to release their first decision until the end of January prompted questions among court watchers and opinion trackers. Such a delay had not been observed in nearly 100 years.

“This slow start has continued this term, which might be related, but I think much has to do with the unexpected Trump cases taking up time that would otherwise be devoted to other cases,” Feldman said, referencing the current cases surrounding Trump and his broad claims of presidential immunity from prosecution, as well as the high court’s opinion earlier this term reversing the Colorado Supreme Court’s decision to rule him ineligible for office.

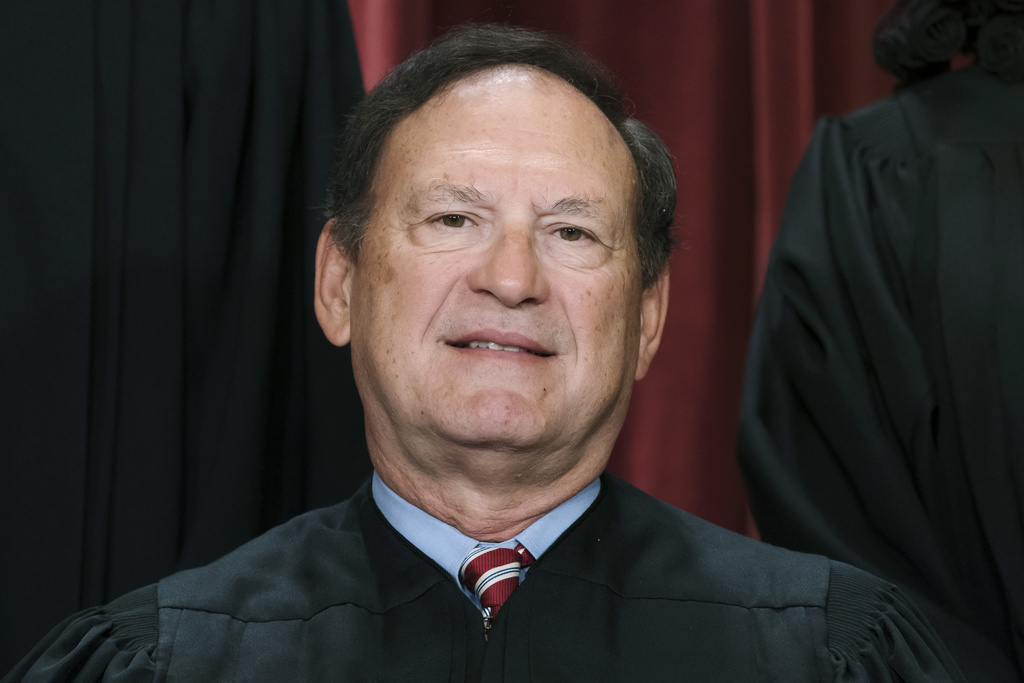

The leak of the opinion via a Politico report sparked a long and tumultuous series of protests between May 2, 2022, and the end of June that year, when the draft 6-3 opinion by Justice Samuel Alito, a staunch conservative on the bench, reversed nearly 50 years of abortion access precedent under Roe v. Wade. Alito’s words were unchanged from the leaked draft when the finalized opinion was released nearly two months later, on June 24.

Nearly two months before that, the Supreme Court on May 5 had erected metal barricades around the building in response to continued protests and threats against Republican-appointed members of the court.

The leak created shockwaves across the nation by signaling the high court would hand the power to impose abortion laws to individual states, and more than a dozen states immediately enacted restrictions or bans on the procedure following that decision.

“I do think the biggest impact that is absolutely ongoing that we have seen is the level of personal threat to justices,” Carrie Severino, a former clerk to Thomas and founder of the conservative JCN, told the Washington Examiner. Likewise, there have been more than 400 attacks against Catholic churches in the United States since May 2020, with numbers skyrocketing after the leaked decision in Dobbs.

The nearly two months between the leak and the final decision gave protesters and agitators ample time to react in ways that put the justices’ lives in danger. Weeks before the final decision came out, a then-26-year-old man from California traveled to the home of Justice Brett Kavanaugh on June 8, 2022, with plans to break in and kill him before he called the police on himself. That man, Nicholas Roske, is currently negotiating a plea deal with prosecutors, according to court records.

“The defense’s mitigation investigation is complete; and the parties have engaged in substantive plea negotiations,” Roske’s public defender wrote in a status report on April 29, which notes a trial is expected to take place from May 13 to June 7.

The murder attempt by Roske prompted the U.S. Marshals Service to send out officers to defend the private homes of several Republican-appointed justices. It wasn’t until an annual dinner at the American Law Institute last May that Roberts admitted the “hardest decision in 18 years” was the decision to place the metal barricades around the court.

“I had no choice but to go ahead and do it,” Roberts said at a dinner last May hosted by the American Law Institute.

But in hindsight, Severino suggested it may have been better overall if the Supreme Court had released the Dobbs decision early rather than wait until the end of the term to release the final ruling.

“I think they wanted to show that they weren’t being affected by it,” Severino said of the leak, adding, “Of course, it can’t really be business as usual” when something like that occurs.

Another concern among the commentariat at the time of the leak was whether it would affect the collegiality among the justices, especially after murmurs and rumors that the source of the leak could have been a justice, an unproven claim that Breyer recently said would leave him “amazed” if it was true.

Feldman said he currently sees the “justices posturing to seem like they get along,” pointing to Democratic-appointed Justice Sonia Sotomayor and Trump-appointed Justice Amy Coney Barrett’s recent speaking engagements with one another in February this year.

“I’m sure the seeds of distrust exist between some of the different chambers, but I think the bottom line is that there isn’t a lot of evidence on the surface that shows things have changed in a negative direction since the Dobbs leak,” Feldman said, adding, “we probably will not have anything that paints a substantially different picture until years later when a justice either releases post-mortem papers to the public or writes a tell-all book.”

Last January, Justice Brett Kavanaugh spoke out about the media’s speculation that the leak had caused any holdups of the Supreme Court’s work, saying it was merely a coincidence that the justices took longer than normal to release their first opinions. He and his colleagues have often raised the point that they eat lunch together and how the court’s relationship and closeness are similar in nature to a family.

Jessie Hill, a constitutional law professor at Case Western Reserve, noted that the intensity of the initial reaction to the Dobbs leak led some people to believe it may “have a lasting impact on the court.”

“I think it had less than it was expected to,” Hill said, noting, “On the other hand, I think the Dobbs decision itself has had more of an impact on our politics, maybe more than people foresaw at the time.”

What remains to be seen is whether the public will have a similar outcry once the justices issue decisions in two separate abortion-related cases this term or in forthcoming consequential decisions in cases involving the former president. A Marquette Law School poll from February found overall approval of the high court floating at around 40%, while 60% of respondents disapproved. That’s still slightly up in comparison to July 2022, which saw approval tank down to 38% in the wake of the Dobbs decision.

One recently argued abortion case involves the potential of limiting access to the common abortion drug, mifepristone, while another surrounds a federal law requiring hospitals to provide emergency abortion care in states with strict bans on such procedures. Both decisions are expected by the end of June.

The immediate aftermath of the leak prompted a flurry of outrage from all sides of the political spectrum, from the left-leaning commentariat who were upset over the sweeping shift of precedent in the Dobbs decision itself to the right-leaning observers who decried the leak as a form of infidelity and institutional sabotage.

In reality, nobody will likely understand the motive or who was behind the leak anytime soon after an internal investigation prompted by Roberts came back inconclusive.

“I suspect maybe one day we’ll find out in some memoir written 50 years from now,” Hill said, adding that for all intents and purposes “this inquiry itself is done.”

Alito, the author of Dobbs, is the only current member of the court who has suggested he has a “pretty good idea” as to who was behind the leak and what may have motivated the breach of the institution. However, the justice has indicated as recently as this spring that it would not be fair to divulge his suspicions publicly without proper evidence. He has, however, poured cold water on the theory that a conservative leaked the decision in some apparent effort to lock in the final vote of the court, arguing it “made us the targets of assassination.”

“Would I do that to myself? Would the five of us have done that to ourselves? It’s quite implausible,” Alito said last April.

For Breyer, an 85-year-old Clinton appointee who retired in 2022, the leak was the end of a fleeting effort to convince his Republican-appointed colleagues to change their position from Alito’s majority opinion despite the only potential holdout being Roberts. Breyer admitted during an interview with NBC News that he was eyeing a “compromise” on a 15-week abortion ban.

The chief justice was the only Republican-appointed justice who did not agree with striking down Roe, but because he ultimately wouldn’t have ruled against Mississippi’s desire to craft its own abortion legislation, he could not bring himself to side with Breyer and the other two Democratic-appointed justices in the minority.

CLICK HERE TO READ MORE FROM THE WASHINGTON EXAMINER

“I always think it’s possible,” Breyer said of the court coming to a compromise. “I always think it’s possible, usually up until the last minute.”

The Washington Examiner contacted the Supreme Court for comment.