In a grand procession last week, Sinai militia leader Ibrahim al-Organi arrived at a ceremony to inaugurate the Arab Tribes Union, a new paramilitary entity that brings together five tribal groups from across Egypt. The celebration named President Abdel Fattah el-Sisi as the union’s "honorary president", while also announcing plans to build Sisi City on the site of al-Arjaa, a village in Rafah near the Egypt-Israel border.

The formation of this alliance comes at a critical time and place, as Israel this week launched a long-threatened ground offensive against the Palestinian city of Rafah, just a short distance from where the Egyptian ceremony was held. Around 1.4 million displaced Palestinians have been sheltering in Rafah since Israel launched its war on Gaza last October.

Israel’s assault on Rafah is likely to cause further mass displacement of Palestinians in Gaza, potentially pushing them towards Egyptian territory. At least 80,000 have already fled Rafah, according to UNRWA, the UN Palestinian refugee agency.

It was thus no coincidence that the union’s founding statement noted its aim to "adopt national issues and connect with all Arab tribes to find common ground within the framework of the state, to serve its objectives, and to support the Egyptian president who seeks to protect Egypt’s national security and its Arab nation against the displacement plans aimed at resolving the Palestinian issue at Egypt’s expense."

Since the outbreak of the Gaza war on October 7, Egyptian officials have repeatedly expressed concerns over the potential displacement of Palestinians to the Sinai. They have even threatened to freeze the country’s peace treaty with Israel.

The historical experiences of Palestinian displacement, along with Israel’s goal to empty historic Palestine of its people, prevent their return and seize their lands, are well known to the Egyptian state.

At the same time, the Palestinian people’s attachment to their land and insistence on their right of return, no matter how long it takes, has made each area of Palestinian displacement - whether in Lebanon, Syria or Jordan - a focal point for resisting the occupation, something Egypt does not want.

All options for dealing with this matter, it seems, are bitter, from the emergence of pockets of Palestinian resistance in the Sinai akin to what happened in Lebanon in the 1970s, to a confrontation of the kind that occurred in Jordan during Black September.

Yet Egypt cannot stop the Israeli military operation, nor halt its tanks from invading the tents of displaced Palestinians in Rafah. The Egyptian regime will not deviate from the US perspective in dealing with the recklessness of Israeli Prime Minister Benjamin Netanyahu, which means it will have to deal directly with the massive crowds of displaced people likely headed towards Egyptian territory.

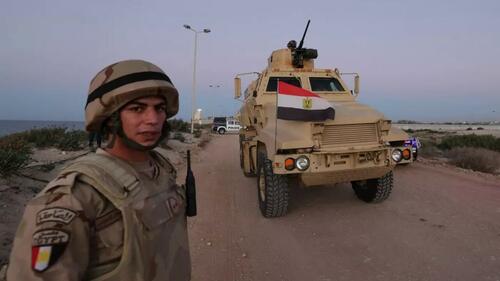

Early on, Egypt started taking precautions for this scenario, overlooking many humanitarian details. It reinforced the fences and barriers along its border with the Gaza Strip, tightened border security, and mobilised support and funding for alternative camps within Gaza itself.

In the event of a mass displacement into its territory, Egypt appears to be planning to confine displaced Palestinians in a high-security, isolated area along the border, allowing the state to maintain tight control and apply pressure to hasten their return to Gaza.

But there are a couple of issues with this plan. For one, many displaced Palestinians have family and tribal ties in the northern Sinai. The Egyptian and Palestinian cities of Rafah were once united as a single city, until Israel’s withdrawal from the Sinai and the demarcation of borders in 1982. Many tribes are still divided, with some members in Palestinian Rafah and others in Egyptian Rafah.

Horrible scenes from the Gaza-Egypt border shows Egyptian military harassing and mishandling a Palestinian boy who managed to slip through the border to escape the onslaught in Rafah. pic.twitter.com/PoaHmxoh82

— روني الدنماركي (@Aldanmarki) May 8, 2024

Tribal customs compel hospitality and reception, which will weaken the ability of the Egyptian state to contain all displaced people in a single area. This could also open the door to fresh confrontations and disputes between state agencies and Sinai tribes.

Simmering public anger

In addition, a wave of displacement would raise significant challenges for Egypt from a military and security perspective. The last thing the Egyptian regime wants is an image of an Egyptian soldier firing at displaced Palestinians, or in any way treating them improperly, amid the unprecedented tragedy in Gaza - especially considering the simmering public anger over the Sisi regime’s handling of the Gaza genocide so far.

Through the newly minted Arab Tribes Union, the regime might have found its only option for handling this situation, while avoiding the direct involvement of state soldiers.

This hypothesis is supported by the union’s founding statement, which notes that its inception "comes in response to the current stage requirements, by creating a national popular framework that includes the sons of the Arab tribes, aimed at unifying the ranks and integrating all tribal entities into a single framework in support of the national state priorities, and facing the challenges that threaten its security and stability."

Organi is a prime choice to lead this task after his previous successes in organizing the Union of Sinai Tribes, which worked alongside the Egyptian army to fight an Islamic State affiliate, and in running companies that manage the movement of people and goods between Gaza and Egypt. But Organi’s companies have also faced allegations of exploitative behavior, including charging millions of dollars from Palestinian refugees fleeing war.

And there are significant risks that under difficult humanitarian conditions, his forces could become involved in smuggling operations, financial extortion, or other types of corruption - not to mention the inherent dangers of forming armed militias, which can prove disastrous to the security and stability of states, sometimes even playing a role in their disintegration.

In a grand procession last week, Sinai militia leader Ibrahim al-Organi arrived at a ceremony to inaugurate the Arab Tribes Union, a new paramilitary entity that brings together five tribal groups from across Egypt. The celebration named President Abdel Fattah el-Sisi as the union’s “honorary president”, while also announcing plans to build Sisi City on the site of al-Arjaa, a village in Rafah near the Egypt-Israel border.

The formation of this alliance comes at a critical time and place, as Israel this week launched a long-threatened ground offensive against the Palestinian city of Rafah, just a short distance from where the Egyptian ceremony was held. Around 1.4 million displaced Palestinians have been sheltering in Rafah since Israel launched its war on Gaza last October.

Israel’s assault on Rafah is likely to cause further mass displacement of Palestinians in Gaza, potentially pushing them towards Egyptian territory. At least 80,000 have already fled Rafah, according to UNRWA, the UN Palestinian refugee agency.

It was thus no coincidence that the union’s founding statement noted its aim to “adopt national issues and connect with all Arab tribes to find common ground within the framework of the state, to serve its objectives, and to support the Egyptian president who seeks to protect Egypt’s national security and its Arab nation against the displacement plans aimed at resolving the Palestinian issue at Egypt’s expense.”

Since the outbreak of the Gaza war on October 7, Egyptian officials have repeatedly expressed concerns over the potential displacement of Palestinians to the Sinai. They have even threatened to freeze the country’s peace treaty with Israel.

The historical experiences of Palestinian displacement, along with Israel’s goal to empty historic Palestine of its people, prevent their return and seize their lands, are well known to the Egyptian state.

At the same time, the Palestinian people’s attachment to their land and insistence on their right of return, no matter how long it takes, has made each area of Palestinian displacement – whether in Lebanon, Syria or Jordan – a focal point for resisting the occupation, something Egypt does not want.

All options for dealing with this matter, it seems, are bitter, from the emergence of pockets of Palestinian resistance in the Sinai akin to what happened in Lebanon in the 1970s, to a confrontation of the kind that occurred in Jordan during Black September.

Yet Egypt cannot stop the Israeli military operation, nor halt its tanks from invading the tents of displaced Palestinians in Rafah. The Egyptian regime will not deviate from the US perspective in dealing with the recklessness of Israeli Prime Minister Benjamin Netanyahu, which means it will have to deal directly with the massive crowds of displaced people likely headed towards Egyptian territory.

Early on, Egypt started taking precautions for this scenario, overlooking many humanitarian details. It reinforced the fences and barriers along its border with the Gaza Strip, tightened border security, and mobilised support and funding for alternative camps within Gaza itself.

In the event of a mass displacement into its territory, Egypt appears to be planning to confine displaced Palestinians in a high-security, isolated area along the border, allowing the state to maintain tight control and apply pressure to hasten their return to Gaza.

But there are a couple of issues with this plan. For one, many displaced Palestinians have family and tribal ties in the northern Sinai. The Egyptian and Palestinian cities of Rafah were once united as a single city, until Israel’s withdrawal from the Sinai and the demarcation of borders in 1982. Many tribes are still divided, with some members in Palestinian Rafah and others in Egyptian Rafah.

Horrible scenes from the Gaza-Egypt border shows Egyptian military harassing and mishandling a Palestinian boy who managed to slip through the border to escape the onslaught in Rafah. pic.twitter.com/PoaHmxoh82

— روني الدنماركي (@Aldanmarki) May 8, 2024

Tribal customs compel hospitality and reception, which will weaken the ability of the Egyptian state to contain all displaced people in a single area. This could also open the door to fresh confrontations and disputes between state agencies and Sinai tribes.

Simmering public anger

In addition, a wave of displacement would raise significant challenges for Egypt from a military and security perspective. The last thing the Egyptian regime wants is an image of an Egyptian soldier firing at displaced Palestinians, or in any way treating them improperly, amid the unprecedented tragedy in Gaza – especially considering the simmering public anger over the Sisi regime’s handling of the Gaza genocide so far.

Through the newly minted Arab Tribes Union, the regime might have found its only option for handling this situation, while avoiding the direct involvement of state soldiers.

This hypothesis is supported by the union’s founding statement, which notes that its inception “comes in response to the current stage requirements, by creating a national popular framework that includes the sons of the Arab tribes, aimed at unifying the ranks and integrating all tribal entities into a single framework in support of the national state priorities, and facing the challenges that threaten its security and stability.”

Organi is a prime choice to lead this task after his previous successes in organizing the Union of Sinai Tribes, which worked alongside the Egyptian army to fight an Islamic State affiliate, and in running companies that manage the movement of people and goods between Gaza and Egypt. But Organi’s companies have also faced allegations of exploitative behavior, including charging millions of dollars from Palestinian refugees fleeing war.

And there are significant risks that under difficult humanitarian conditions, his forces could become involved in smuggling operations, financial extortion, or other types of corruption – not to mention the inherent dangers of forming armed militias, which can prove disastrous to the security and stability of states, sometimes even playing a role in their disintegration.

Loading…