Authored by Nick Binotti and Ted Dabrowski via Wirepoints.org,

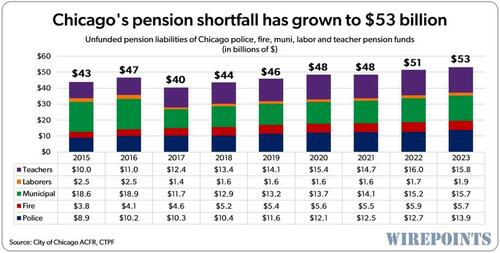

Wirepoints recently warned in a Chicago Sun-Times oped that Chicago’s pension mess was going to get worse. As Chicago’s latest annual financial report shows, that’s just what happened.

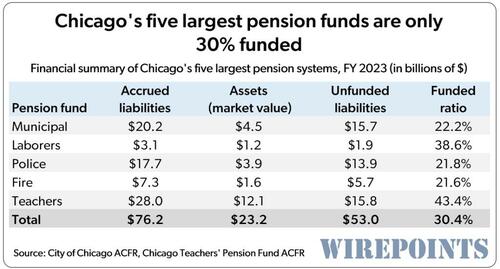

Chicago’s pension shortfall across the city’s four major retirement funds – Municipal, Laborers, Police and Fire – rose to $37.2 billion total in 2023. That’s a 5% increase from $35.4 billion reported the prior year. Most of the increase is attributed to changes in actuarial assumptions and recent legislation that sweetened the cost-of-living pension benefit for thousands of police and firefighters.

Add in the Teachers Pension Fund’s $15.8 billion shortfall and Chicagoans are on the hook for $53 billion in unfunded pension liabilities. That’s over $45,000 owed per Chicago household to be paid off over time.

The Chicago teachers and municipal pension funds have the highest unfunded liabilities with both just under $16 billion. The police pension fund is next with nearly $14 billion. The fire and laborers pension systems have unfunded liabilities of $5.7 billion and $1.9 billion, respectively.

Chicago’s five largest systems are only 30% funded collectively. Only the Chicago Teachers Pension Fund has a funding ratio above 40%. Chicago’s municipal, police and fire pension systems each have funding ratios around only 22%, among the worst in the country for major pension funds.

Chicago’s pension debt continues to increase slowly and steadily year after year. It’s what we described as a “slow-boil” where Chicagoans are increasingly burdened with higher taxes for the same or less amount of services, disparately impacting the city’s most vulnerable.

Mayor Brandon Johnson Pension Working Group has yet to come up with a plan to cool down that boil. In an open letter to Mayor Johnson and an Oped in the Chicago Tribune, Wirepoints and the Taxpayer Pension Alliance outlined a number of actions the city could take to get some control over the problem.

Here are key measures of Chicago’s crisis we provided to the mayor on January 10, 2024:

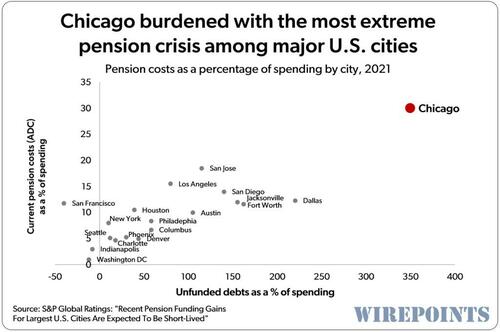

Chicago’s pension costs and its unfunded liability make the city the extreme outlier nationally when it comes to the burden it creates on its residents and its budget.

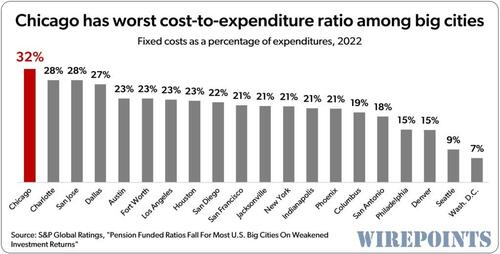

The fixed costs of Chicago’s pension and general debts makes the city uncompetitive vis-a-vis the nation’s other big cities. Those costs will continue to negatively impact taxes and services, further pressuring the city’s out-migration, home values and quality-of-life issues.

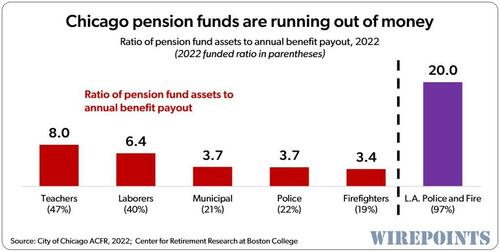

Chicago’s pension funds are running out of money and are among the worst funded in the country when measured by the ratio of assets a plan has relative to its yearly payout. Those asset-to-payout ratios have collapsed to single digits over the last two decades, reflecting the funds’ fall towards insolvency. Healthy funds have a ratio of 20 or more.

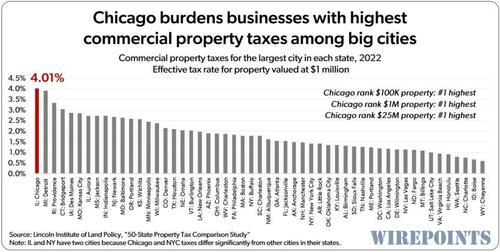

Chicago can’t increase taxes without inflicting even more damage to its economic competitiveness. Chicago commercial property taxes are already the nation’s highest among big cities.

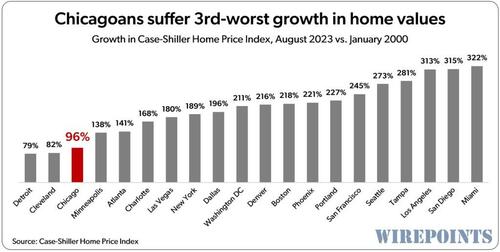

The city’s lack of competitiveness across fiscal and quality-of-life issues, including crime and education, has had a dramatic impact on Chicagoans’ home values. The expectation of higher taxes and cuts in services will continue to put pressure on Chicago home values.

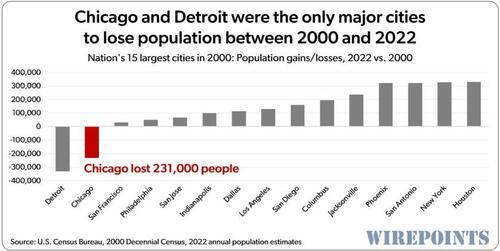

The catch-all impact of the burdens and quality-of-life issues Chicagoans face is reflected by the city’s long-term population decline. When compared to the turn of the millennium, Chicago and Detroit are the only major cities to suffer a loss of people.

Chicago has the worst credit rating in the country among big cities with the exception of Detroit. Chicago was able to shed its junk rating only because of the billions in federal public and private aid during covid. The city’s pension crisis will reemerge as those federal funds dry up.

* * *

Chicago’s pension crisis will not be solved via more reamortizations, pension obligation bonds or tax hikes. Such “fixes” will only prolong and further exacerbate the city’s housing, migration and quality-of-life issues. Instead, a comprehensive, long-term solution, based on actuarial best practices, is essential to restoring confidence and competitiveness to Chicago.

Authored by Nick Binotti and Ted Dabrowski via Wirepoints.org,

Wirepoints recently warned in a Chicago Sun-Times oped that Chicago’s pension mess was going to get worse. As Chicago’s latest annual financial report shows, that’s just what happened.

Chicago’s pension shortfall across the city’s four major retirement funds – Municipal, Laborers, Police and Fire – rose to $37.2 billion total in 2023. That’s a 5% increase from $35.4 billion reported the prior year. Most of the increase is attributed to changes in actuarial assumptions and recent legislation that sweetened the cost-of-living pension benefit for thousands of police and firefighters.

Add in the Teachers Pension Fund’s $15.8 billion shortfall and Chicagoans are on the hook for $53 billion in unfunded pension liabilities. That’s over $45,000 owed per Chicago household to be paid off over time.

The Chicago teachers and municipal pension funds have the highest unfunded liabilities with both just under $16 billion. The police pension fund is next with nearly $14 billion. The fire and laborers pension systems have unfunded liabilities of $5.7 billion and $1.9 billion, respectively.

Chicago’s five largest systems are only 30% funded collectively. Only the Chicago Teachers Pension Fund has a funding ratio above 40%. Chicago’s municipal, police and fire pension systems each have funding ratios around only 22%, among the worst in the country for major pension funds.

Chicago’s pension debt continues to increase slowly and steadily year after year. It’s what we described as a “slow-boil” where Chicagoans are increasingly burdened with higher taxes for the same or less amount of services, disparately impacting the city’s most vulnerable.

Mayor Brandon Johnson Pension Working Group has yet to come up with a plan to cool down that boil. In an open letter to Mayor Johnson and an Oped in the Chicago Tribune, Wirepoints and the Taxpayer Pension Alliance outlined a number of actions the city could take to get some control over the problem.

Here are key measures of Chicago’s crisis we provided to the mayor on January 10, 2024:

Chicago’s pension costs and its unfunded liability make the city the extreme outlier nationally when it comes to the burden it creates on its residents and its budget.

The fixed costs of Chicago’s pension and general debts makes the city uncompetitive vis-a-vis the nation’s other big cities. Those costs will continue to negatively impact taxes and services, further pressuring the city’s out-migration, home values and quality-of-life issues.

Chicago’s pension funds are running out of money and are among the worst funded in the country when measured by the ratio of assets a plan has relative to its yearly payout. Those asset-to-payout ratios have collapsed to single digits over the last two decades, reflecting the funds’ fall towards insolvency. Healthy funds have a ratio of 20 or more.

Chicago can’t increase taxes without inflicting even more damage to its economic competitiveness. Chicago commercial property taxes are already the nation’s highest among big cities.

The city’s lack of competitiveness across fiscal and quality-of-life issues, including crime and education, has had a dramatic impact on Chicagoans’ home values. The expectation of higher taxes and cuts in services will continue to put pressure on Chicago home values.

The catch-all impact of the burdens and quality-of-life issues Chicagoans face is reflected by the city’s long-term population decline. When compared to the turn of the millennium, Chicago and Detroit are the only major cities to suffer a loss of people.

Chicago has the worst credit rating in the country among big cities with the exception of Detroit. Chicago was able to shed its junk rating only because of the billions in federal public and private aid during covid. The city’s pension crisis will reemerge as those federal funds dry up.

* * *

Chicago’s pension crisis will not be solved via more reamortizations, pension obligation bonds or tax hikes. Such “fixes” will only prolong and further exacerbate the city’s housing, migration and quality-of-life issues. Instead, a comprehensive, long-term solution, based on actuarial best practices, is essential to restoring confidence and competitiveness to Chicago.

Loading…