President Joe Biden isn’t on the November ballot but his administration has been working overtime to “Trump-proof” science before his exit, putting protections in place to shield government scientists from political interference should former President Donald Trump win another White House term.

“The Trump administration regularly suppressed, downplayed, or simply ignored scientific research demonstrating the need for regulation to protect public health and the environment,” Romany Webb, deputy director of the Sabin Center for Climate Change Law at Columbia Law School, wrote.

She added that the Trump administration “routinely prioritized economic interests” over health and science and encouraged a public distrust of science.

Silencing science

The Trump administration’s efforts to “undermine science” has been documented in the Silencing Science Tracker, an online database with more than 300 entries that records anti-science actions taken by local, state, and federal governments. It has been tracking complaints since November 2016. Trump was sworn into office on Jan. 20, 2017.

Jennifer Jones, director for the Center for Science and Democracy at the Union of Concerned Scientists, told the Washington Examiner that while “there is always an urgent need to defend science” there was an uptick in dissatisfied scientists during the previous administration.

“I just can’t stress enough how our daily lives depend on good, independent science, free of political interference,” she said.

Scientists and those who want to protect evidence-based policymaking have several options in play. They include establishing a scientific integrity council, codifying laws prohibiting political interference with the scientific research and federal data used to protect the public, and using collective bargaining agreements negotiated by unions to protect scientists and their work.

National Institutes of Health

Lyric Jorgenson, the associate director for science policy at the National Institutes of Health, said the plan to safeguard the agency’s independence is critical to its mission.

“Interfering and manipulating science to hit a partisan agenda is inappropriate and is what we’re working to wall against,” she told Politico.

NIH is the country’s primary federal agency for medical research. The public needs to be able to believe in its accuracy to “generate rigorous, trusted evidence to inform public health,” Jorgenson added.

The agency, which is made up of 27 different components called institutes and centers, spends more than $40 billion a year on research and has largely operated politics-free. Its roots trace back to 1887, when a one-room laboratory was created within the Marine Hospital Service, a predecessor agency to the U.S. Public Health Service.

NIH gained prominence and visibility during the Covid-19 global pandemic. And while most turned to the NIH for guidance, some did not.

As president, Trump pitched hydroxychloroquine as a possible Covid-19 treatment and repeatedly threatened to fire Dr. Anthony Fauci, the nation’s top infectious-disease expert. Their relationship publicly soured after they clashed over the White House’s response to the pandemic, which claimed more than 1.1 million American lives.

Fauci faced partisan attacks as Trump publicly entertained the idea of firing him, something he technically couldn’t do.

Schedule F

But now, there is concern by some in the scientific community that if Trump returns for a second term, he might try to re-classify career civil servants, non-partisan government scientists, and fire them at will if he doesn’t like what they have to say or feels they aren’t loyal to him.One month before the 2020 presidential election, the Trump administration issued an executive order that would have done just that. The effort, referred to as “Schedule F,” would have created a new employment category.

“Because Trump did not remain in office, it is unknown how many federal employees his administration would have swept into Schedule F, or how many would have been fired and replaced,” according to the nonprofit, Protect Democracy.org. “Experts have put the possible numbers in the tens or hundreds of thousands. The Trump official credited with the idea to create Schedule F estimated that it could apply to as many as 50,000 federal workers.”

Some Trump allies told Axios it would not be necessary to fire that many workers because firing fewer would produce the desired “behavior change.”

National Weather Service

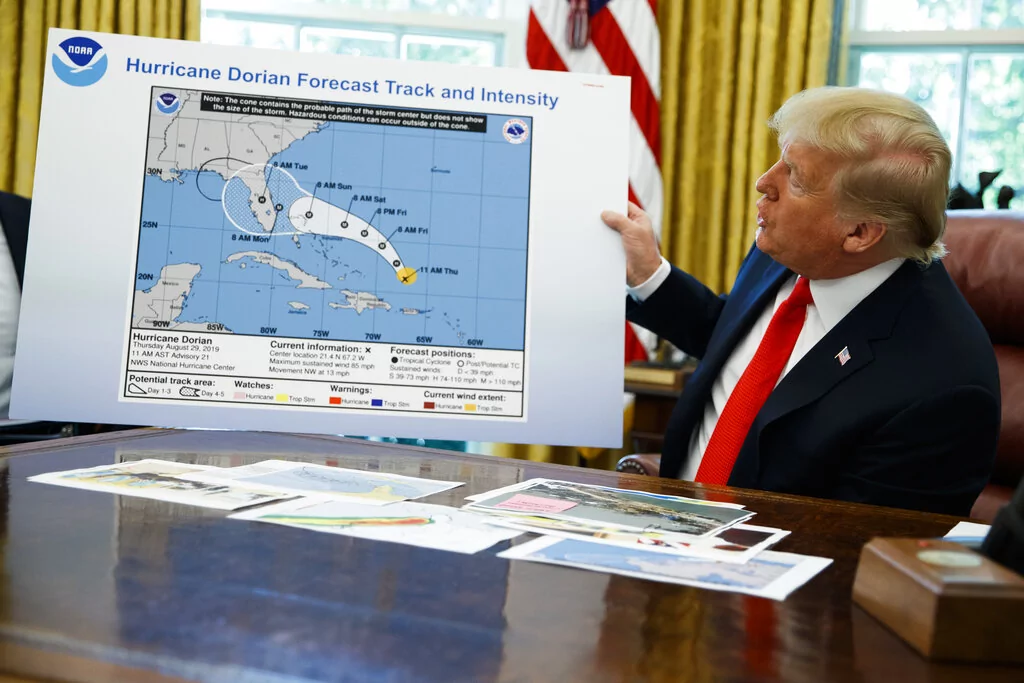

Trump also came under scrutiny for “Sharpie-gate.”

In September 2019, he displayed a National Weather Service map in the Oval Office showing Hurricane Dorian’s cone of uncertainty, which identifies the probable paths of the storm’s center. Trump had insisted on Twitter that Dorian was going to hit Alabama “harder than anticipated.” The problem was that it wasn’t and that the map had been altered with a Sharpie to indicate that it was.

The Birmingham office of the National Weather Service had to issue a statement emphasizing that Alabama would not actually be affected. That statement, directly contradicting the president, led to threats by the administration to fire top employees.

The threat of unemployment led to an unsigned statement by the National Oceanic and Atmospheric Administration disavowing the National Weather Service’s position that Alabama was not at immediate risk. The move caused anger and accusations from the scientific community that NOAA had bent to political pressure from the president.

“We come at this work with the understanding that all of our lives are dependent on federal agencies using the best available science whether it’s tracking a dangerous storm, analyzing the impacts of air pollution, or protecting us from infectious diseases like Covid-19,” Jones said. “We want to make sure that policy, rule making, and laws are informed by the best available science and that that science is communicated to the public.”

Scientific integrity policies

One way Jones told the Washington Examiner is for federal agencies to adopt interim scientific integrity policies.

“If you look across the federal government, you’ll see different federal agencies are in different stages of having adopted an interim scientific integrity policy,” she said. “Some of them have produced policies that they’ve put up on the federal register and sent out for comment. The EPA [Environmental Protection Agency] falls in that bucket. They posted their most recent version in February. You are going to see a number of agencies produce their final scientific integrity policies by the end of the year.”

Unions

Another path forward for scientists are collective bargaining agreements negotiated by their unions.

Nicole Cantello, a legislative and political coordinator for the union that represents more than half of the Environmental Protection Agency’s 15,000-plus workforce, told Nature that the Trump administration’s heavy handed approach to science came as a surprise.

“We really were not prepared to defend the agency the first time around,” she said, calling the administration’s dismissal of science unprecedented. “People don’t want to experience that again and are gearing up for a fight.”

Provisions that protect government workers who stand up for scientific integrity were also included in union contracts for U.S. Department of Agriculture workers. Negotiators for the union representing 5,000 early-career scientists at the NIH are also pushing for protections.

Congress

In Congress, a group of bipartisan lawmakers have thrown their weight behind the Scientific Integrity Act.

Rep. Paul Tonko (D-NY) introduced the legislation that would set “clear, enforceable standards for federal agencies and federally-funded research to keep public science independent from political and special interest meddling.”

“Public science must be about the pursuit of truth – not about serving political objectives,” Tonko said in a statement. “As one of only a few engineers in Congress, I’ve worked for many years to ensure that scientific standards are upheld regardless of who sits in the White House.”

While Trump has been getting the lion’s share of the blame, Jones told the Washington Examiner that almost every single administration – Republican and Democrat- has injected politics into science.

CLICK HERE TO READ MORE FROM THE WASHINGTON EXAMINER

“For years we have been pushing for policies across administrations because the need to protect science and scientists is of utmost importance,” Jones said. “We always watch every election very carefully. We know that our elected officials play a big role in shaping the use of science and the culture of science that any agency might adopt.”

Emails to Trump’s campaign seeking comment were not returned.