Authored by Conor Gallagher via Naked Capitalism,

The RAND Corporation, one of the more influential US think tanks that help craft US foreign policy, is out with a new paper arguing that it’s time the US use a divide and rule strategy with Beijing and Moscow in the Arctic. Years of sanctions, threats, and general belligerence from Washington helped organize the wedding of China and Russia’s complementary economies, and that’s increasingly evident in the Arctic where the two are cooperating on development, trade routes, and oil and gas projects. Here’s RAND now sounding the alarm:

What might be done to limit China-Russia cooperation in this geopolitically important region? RAND researchers consider this question in a new paper, concluding that Western policies focusing on the differences between Beijing and Moscow may be effective. To put such a strategy into action, the United States and its northern NATO allies could develop separate approaches for dealing with China and Russia when it comes to Arctic affairs.

The authors (Dr. Abbie Tingstad ,a visiting professor of Arctic research at the Center for Arctic Study and Policy, U.S. Coast Guard Academy; Stephanie Pezard, an associate research department director, Defense and Political Sciences, and a senior political scientist at RAND; and Yuliya Shokh, a U.S. Air Force intelligence analyst and technical analyst at RAND.) also note the following:

…there may be no need to drive a wedge between Russia and China in the region. That’s because one may already exist: The two countries have very different Arctic interests, influence, and postures—not to mention a difficult history together.

My first thought was that these people are crazy — or are paid to be so. You could maybe convince yourself it would be feasible if the US wasn’t doing its best to bring Moscow and Beijing together with all its sanctioning, bombing, and arming as it’s unlikely that Communist differences from decades ago are going to be a bigger factor than the immediate threat posed by an unhinged and violent US.

Yet in the aftermath of the Syria shock, maybe it’s not a bad time to doublecheck RAND’s details of the Russia-China relationship. Not only is the Moscow-Beijing “no limits” partnership one of the biggest geopolitical developments of recent years, but it is also one that the US continues to help bring about. And it looks set to continue to do so whether following a path set forth by RAND or one of even more doubling down as laid out in a December special report from the Council on Foreign Relations.

Let’s look at what RAND highlights as signs of present and potential friction between Russia and China over the Arctic and Russia’s Far East.

Is the relationship headed toward benign neglect or even divorce because China increasingly sees Russia as a destabilizing influence that counters its Arctic aspirations? A potential breakdown in Sino-Russian relations has been foretold by the still low or nonexistent numbers of Chinese vessels transiting the [Northern Sea Route], Beijing’s apparent growing apathy to Russia’s Power of Siberia 2 gas pipeline proposal, and the 2020 arrest of Russian lecturer Valery Mitko on spying charges.

Let’s look at each one of these points:

Despite the holdup on Power of Siberia 2, Russian pipeline gas exports to China are at new records. As of December 1, Gazprom increased supplies to the equivalent of 38 billion cubic meters per year. That’s roughly nine percent of China’s consumption this year.

Mitko, a researcher of the Arctic region and one of Russia’s leading hydroacoustics experts, was accused of revealing sensitive data during a 2018 academic trip to China. He denied the charges but was under house arrest from 2020 until his death in 2022. The issue never posed any serious threat to expanding ties between the two countries, although it’s feasible that continued future similar cases could cause headaches.

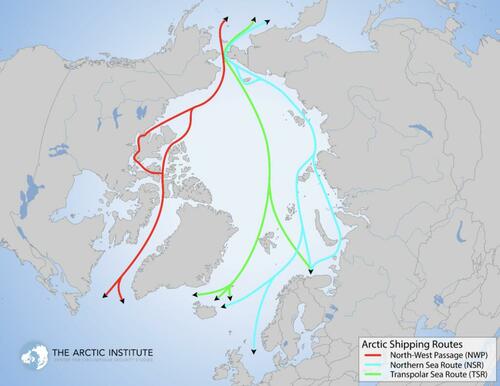

How about the lack of Chinese vessels on the Northern Sea Route (NSR)?

While the authors are correct that traffic remains low on the shortest route between the western part of Eurasia and the Asia-Pacific region, that doesn’t mean it will remain that way, and they also omit recent milestones. Here’s one from late 2023 courtesy of Maritime Executive:

In another demonstration of the efforts to expand shipping along Russia’s Northern Sea Route, the Chinese-owned containership Newnew Polar Bear (15,950 dwt) became the first to reach the Russian port in Kaliningrad after a six-week passage. The governor of the Kaliningrad region Anton Alikhanov hailed the achievement on his Telegram account.

The vessel was acquired earlier this year by a new Chinese shipping company, Hainan Yangpu Newnew Shipping Co., and ushered in the route sailing from St. Petersburg at the beginning of July. She started the return trip from China in late August, reaching Kaliningrad on Tuesday and spending three days on dock. The ship registered in Hong Kong is 554 feet long with a capacity of 1,600 TEU.

She is part of the effort to expand trade between China and Russia and grow traffic along the Northern Sea Route. President Vladimir Putin has ordered the authorities overseeing the route to boost annual shipments to 80 million metric tons in 2024.

“Transport companies plan to make this logistics product permanent. It turns out cheaper and faster than through the Suez Canal,” writes Alikhanov touting the party line on his Telegram account.

Additionally in June Russian state nuclear agency Rosatom signed an agreement with Chinese line Hainan Yangpu New Shipping to potentially operate a year-round route. The deal also involves collaboration in the design and construction of new ice-class container ships. In a historic first, two Chinese container ships crossed paths on the route on September 11. It might not be the last time — although much work remains to be done building up infrastructure along the NSR. Yet the US is providing both Moscow and Beijing with incentives to pursue just that with its isolation efforts. While the NSR might not become a primary route for China, it does provide another option, and it also shortens shipping times with Europe by up to 50 percent compared to the Suez route, and Russia will rake in profits from transit fees.

The RAND authors continue:

Russia has been wary of the presence of non-Arctic countries in this region, especially regarding military activity. Despite the declaration of a limitless friendship with China, Russia has not provided Beijing with opportunities to conduct overt military operations directly in and around the Arctic Zone of the Russian Federation (AZRF). Compared with the growing frequency and scale of U.S. cooperation with Norway on Arctic military training and exercises, sailing a few destroyers well below the Arctic Circle pales in comparison.

I’m unsure how much a contest over military exercises tells us. Nonetheless, what’s indisputable is that China’s footprint continues to grow even if it’s not to the level of US training and exercises in Norway.

In October, for example, China’s Coast Guard entered Arctic Ocean waters for the first time as part of a joint patrol with Russia. Four vessels from the Russian Border Guard and Chinese Coast Guard were spotted by the US in the Bering Sea – the northernmost location it said it had ever observed the Chinese ships. And in July US and Canadian forces intercepted Russian and Chinese bombers flying together near Alaska for the first time.

Part of the reason for such moves is to send a message to Washington whose military activities in the South and East China Seas and arming of Taiwan are not well-received in Beijing.

Energy and the Far East

Here’s RAND on the proposed Power of Siberia 2 pipeline:

Similarly, China has not written a blank check for Russia to develop its Siberian energy reserves. To the contrary, Moscow has been unable to convince Beijing, as of the time of this publication, to fund the larger capacity Power of Siberia 2 pipeline, despite numerous meetings between these countries’ leadership. There are several potential reasons for this lack of funding: One is that China is waiting for an even better deal on energy resources; another is that Beijing could be wary of being overly dependent on Russia for energy…

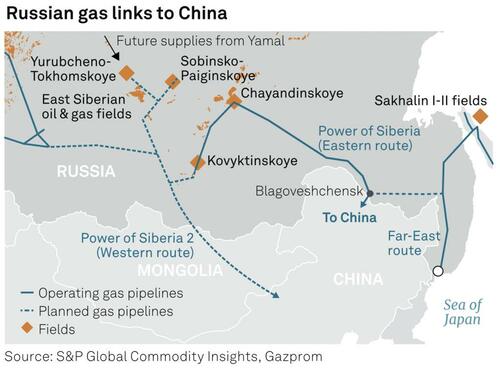

Power of Siberia 2 (PS2) is a proposed pipeline that would have the capacity to carry 50 billion cubic meters per year from Russia to China, but the two sides are struggling to come to an agreement on price.

PS2 is often overblown in the Western media. While Russia has both economic and geopolitical reasons for wanting to get a deal done, it doesn’t want to give the gas away.

And China currently has other options, including pipeline gas from Central Asia and LNG suppliers such as Qatar. Its demands are currently met by existing contracts and might not need the gas from PS2 prior to the mid-2030s. It could be attractive, however, due to US efforts to control China’s rise and its energy supply and Beijing’s reluctance to rely too heavily on LNG from the likes of Australia and the US.

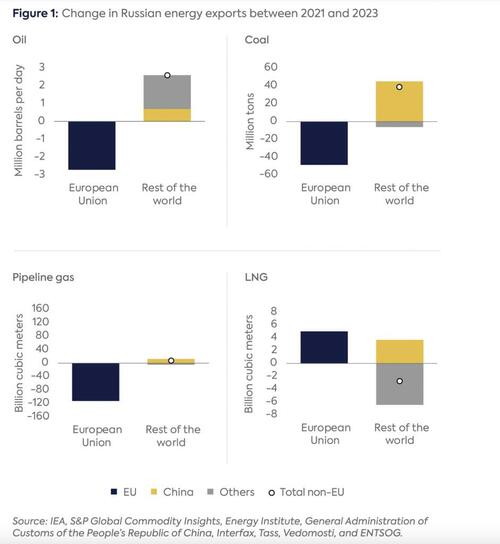

Less mentioned is that Russia also has options. It continues to increase LNG exports — largely to China — and has a goal to triple overall exports by 2030. China would play a huge real in achieving that goal, but that would make PS2 unlikely. Either way the gas is getting to China, and Russia is doing just fine with its energy exports:

The problem for the US is that further tightening sanctions on Russia makes Moscow more dependent on China, which benefits Beijing.

Any attempt to isolate China (say by cutting LNG from Australia and Middle East or pipelines from Central Asia) makes China more dependent on Russia.

Even without PS2 China is already getting 38 bcm through the original Power of Siberia. Starting in 2027, gas will also go to China via the Far Eastern route, which is set to have a capacity of some 10 Bcm/year. That’s 48 bcm per year is already a massive amount. A useful map from S&P Global:

With the heavy focus on PS2, RAND (and others) also miss all the other developments in Russia’s Far East. Let’s take a quick look.

Over the past ten years, Russia has laid more than 2,000 kilometers of railway tracks and renovated more than 5,000 kilometers on the Trans-Siberian Railway and the Baikal-Amur Mainline.

Russia’s Baikal-Amur Mainline: Great Nothern Railway marks its 50th anniversary

— Sputnik (@SputnikInt) April 23, 2024

Today one of the longest railways in the world — Russia’s Baikal-Amur Mainline (BAM) — is celebrating its half-century anniversary.

BAM now largely determines global logistics for the entire 21st… pic.twitter.com/E4XkXBSJWc

By the end of this year, the carrying capacity of these networks is expected to reach 180 million tonnes — an increase of 36 million since 2021. More than 3,100 kilometers of tracks are planned for the next eight years, as well, which will help Moscow meet international demand for resources from its East.

China and Russia are also working together to increase the capacity of resources heading to the former. In 2022, they opened the lone vehicle bridge crossing the Amur River, which forms more than 1,600 of their roughly 4,000 border kilometers. Later that year they opened the Tongjiang Bridge, currently the only railway bridge connecting the two countries. It shortens the journey between China’s Heilongjiang region and Moscow by more than 800 kilometers over previous routes, saving 10 hours of transit time. This helped rail transport between the two countries jump to 161 million tonnes in 2023, a 36 percent increase from 2022. Over the first five months of this year, it grew another 20 percent.

A second railway bridge over the Amur is coming soon and will provide Russia’s resource-rich Sakha Republic with direct access to China. The new route will be 2,000 kilometers shorter than the current one which involves the use of sea ports. Beijing is investing in this railway construction in the Sakha Republic as part of a new international corridor in the Russian Far East: the Mohe-Magadan railway line.

RAND wraps up its rundown of China-Russia trouble in paradise with hypotheticals that, while possible, start to sound a little desperate:

The Arctic relationship between Russia and China could be damaged by a hypothetical diplomatic clash - for instance, if China were to precipitate a major safety or environmental incident in the vicinity of the Russian Arctic or somehow publicly embarrass Moscow by undermining the perception that Russia exerts full control over its Arctic region. More broadly, some serious indications that China might represent a direct and immediate military threat to Russia in the Arctic could lead to a backlash from Moscow.

How is the US supposed to exploit these points of contention? RAND argues the following:

Western policies that focus on differences between Russia and China may ultimately be more successful in shaping the Arctic’s future than those that emphasize their similarities or their relationship itself as the primary driver of regional outcomes….

Chinese growing interest in Arctic resources does not necessarily translate to a stronger dependence on Russia alone…China’s relationship with the United States is a big influence on this scenario’s probability; six of the seven other Arctic countries (except Russia) are allies, militarily and otherwise, of the United States. This scenario would assume a reversal of these countries’ existing preference to watch closely—and deny more often than not—China’s efforts to invest in such sectors as real estate and critical technologies. This scenario also offers a reminder that although the Sino-Russian relationship is important, the mere existence of their relationship is not the only determinant to how China can potentially extend its influence in the region…

One key policy decision by the United States and its northern NATO allies could be to develop separate strategies for dealing with Moscow and Beijing when it comes to Arctic affairs.

What does that look like? Conveniently, more of the same, which means the US doesn’t have to do much of anything other than stay the course and wait:

The Western Arctic countries yield strong potential to realize their interests and diminish the power of the Sino-Russian relationship by developing policies that (1) recognize Russia as an aggressive, risk-taking, but ultimately legitimate Arctic state and (2) recognize that China has no innate influence in the Arctic and pursues a vested interest in maintaining good economic and scientific relationships with all Arctic nations. There may be no need to drive a wedge between Russia and China in the Arctic because it already exists through their differences as Arctic actors and difficult history together.

RAND, to its credit, does admit is that much of the Russian-Chinese cooperation is mutually beneficial:

…the Sino-Russian relationship is driven by Russia’s need for funding and technology to develop its Arctic region, especially because its pool of investors waned with the invasion of Ukraine and sanctions, and by China’s desire to gain a foothold in the region and tap into Russia’s hydrocarbon resources and access to the NSR for Arctic navigation.

Furthermore:

Russia and China have forged a cooperative relationship that has (at least to some measure) helped Russia to further develop its northern economy and afforded China tangible opportunities to establish itself as a recognized stakeholder in the region. The most prominent example is the investment of Chinese companies in two liquid natural gas (LNG) projects in the Yamalo- Nenets Autonomous Okrug in northern Siberia and the Power of Siberia 1 pipeline.27 Overall, China has invested billions of dollars in energy and mining projects in Russia’s Arctic, although the bulk of its investment in Russia (and across the Arctic writ large) is in Yamal LNG, which is a massive undertaking.28 In addition, the Chinese transportation company COSCO SHIPPING Lines Co., Ltd., has been exploring the use of the NSR running along Russia’s Arctic coastline as an option for future global logistics.

RAND does not, however, consider one the driving forces behind the increased cooperation: the current policy of the US and its vassals. And when you add that factor to the mix, it shows why a Moscow-Beijing split is unlikely. Even if the US and its Arctic allies try to develop separate policies for Beijing and Moscow, the latter two would still have the incentive to work together. Indeed, what makes the NSR more attractive isn’t just how short a route it is between Europe and Asia; it’s that its 5,600 kilometers are controlled by just one country (Russia), which means it faces less potential chokepoints than others.

A big part of that is because of how the West bailed on Russian Arctic projects.

Much of Russia’s plans for the extraction and delivery of its Arctic resources previously involved the West, but that, of course, is no longer the case. European shipping companies mostly cut ties with Russian operators in 2022. As part of the economic war against Russia, Western partners abandoned Northern Sea energy projects. At first, traffic fell off a cliff, but it has since rebounded and now looks set to grow exponentially into the future with both Beijing and Moscow being the biggest winners. According to Silk Road Briefing, “a central hub for building large-capacity offshore structures to produce liquefied natural gas (LNG) on a very large scale is underway based in Murmansk. Russia is active in boosting the production of sea-borne super-cooled gas as its pipeline gas exports to Europe, once a key source of revenue for Moscow, have plummeted amid the Western sanctions imposed over the conflict in Ukraine. Those resources are now being directed East, where consumer demand is far greater.”

And yet the RAND authors propose the US keep up the very policies that are driving Moscow and Beijing together in a bid to drive a wedge between them.

Authored by Conor Gallagher via Naked Capitalism,

The RAND Corporation, one of the more influential US think tanks that help craft US foreign policy, is out with a new paper arguing that it’s time the US use a divide and rule strategy with Beijing and Moscow in the Arctic. Years of sanctions, threats, and general belligerence from Washington helped organize the wedding of China and Russia’s complementary economies, and that’s increasingly evident in the Arctic where the two are cooperating on development, trade routes, and oil and gas projects. Here’s RAND now sounding the alarm:

What might be done to limit China-Russia cooperation in this geopolitically important region? RAND researchers consider this question in a new paper, concluding that Western policies focusing on the differences between Beijing and Moscow may be effective. To put such a strategy into action, the United States and its northern NATO allies could develop separate approaches for dealing with China and Russia when it comes to Arctic affairs.

The authors (Dr. Abbie Tingstad ,a visiting professor of Arctic research at the Center for Arctic Study and Policy, U.S. Coast Guard Academy; Stephanie Pezard, an associate research department director, Defense and Political Sciences, and a senior political scientist at RAND; and Yuliya Shokh, a U.S. Air Force intelligence analyst and technical analyst at RAND.) also note the following:

…there may be no need to drive a wedge between Russia and China in the region. That’s because one may already exist: The two countries have very different Arctic interests, influence, and postures—not to mention a difficult history together.

My first thought was that these people are crazy — or are paid to be so. You could maybe convince yourself it would be feasible if the US wasn’t doing its best to bring Moscow and Beijing together with all its sanctioning, bombing, and arming as it’s unlikely that Communist differences from decades ago are going to be a bigger factor than the immediate threat posed by an unhinged and violent US.

Yet in the aftermath of the Syria shock, maybe it’s not a bad time to doublecheck RAND’s details of the Russia-China relationship. Not only is the Moscow-Beijing “no limits” partnership one of the biggest geopolitical developments of recent years, but it is also one that the US continues to help bring about. And it looks set to continue to do so whether following a path set forth by RAND or one of even more doubling down as laid out in a December special report from the Council on Foreign Relations.

Let’s look at what RAND highlights as signs of present and potential friction between Russia and China over the Arctic and Russia’s Far East.

Is the relationship headed toward benign neglect or even divorce because China increasingly sees Russia as a destabilizing influence that counters its Arctic aspirations? A potential breakdown in Sino-Russian relations has been foretold by the still low or nonexistent numbers of Chinese vessels transiting the [Northern Sea Route], Beijing’s apparent growing apathy to Russia’s Power of Siberia 2 gas pipeline proposal, and the 2020 arrest of Russian lecturer Valery Mitko on spying charges.

Let’s look at each one of these points:

Despite the holdup on Power of Siberia 2, Russian pipeline gas exports to China are at new records. As of December 1, Gazprom increased supplies to the equivalent of 38 billion cubic meters per year. That’s roughly nine percent of China’s consumption this year.

Mitko, a researcher of the Arctic region and one of Russia’s leading hydroacoustics experts, was accused of revealing sensitive data during a 2018 academic trip to China. He denied the charges but was under house arrest from 2020 until his death in 2022. The issue never posed any serious threat to expanding ties between the two countries, although it’s feasible that continued future similar cases could cause headaches.

How about the lack of Chinese vessels on the Northern Sea Route (NSR)?

While the authors are correct that traffic remains low on the shortest route between the western part of Eurasia and the Asia-Pacific region, that doesn’t mean it will remain that way, and they also omit recent milestones. Here’s one from late 2023 courtesy of Maritime Executive:

In another demonstration of the efforts to expand shipping along Russia’s Northern Sea Route, the Chinese-owned containership Newnew Polar Bear (15,950 dwt) became the first to reach the Russian port in Kaliningrad after a six-week passage. The governor of the Kaliningrad region Anton Alikhanov hailed the achievement on his Telegram account.

The vessel was acquired earlier this year by a new Chinese shipping company, Hainan Yangpu Newnew Shipping Co., and ushered in the route sailing from St. Petersburg at the beginning of July. She started the return trip from China in late August, reaching Kaliningrad on Tuesday and spending three days on dock. The ship registered in Hong Kong is 554 feet long with a capacity of 1,600 TEU.

She is part of the effort to expand trade between China and Russia and grow traffic along the Northern Sea Route. President Vladimir Putin has ordered the authorities overseeing the route to boost annual shipments to 80 million metric tons in 2024.

“Transport companies plan to make this logistics product permanent. It turns out cheaper and faster than through the Suez Canal,” writes Alikhanov touting the party line on his Telegram account.

Additionally in June Russian state nuclear agency Rosatom signed an agreement with Chinese line Hainan Yangpu New Shipping to potentially operate a year-round route. The deal also involves collaboration in the design and construction of new ice-class container ships. In a historic first, two Chinese container ships crossed paths on the route on September 11. It might not be the last time — although much work remains to be done building up infrastructure along the NSR. Yet the US is providing both Moscow and Beijing with incentives to pursue just that with its isolation efforts. While the NSR might not become a primary route for China, it does provide another option, and it also shortens shipping times with Europe by up to 50 percent compared to the Suez route, and Russia will rake in profits from transit fees.

The RAND authors continue:

Russia has been wary of the presence of non-Arctic countries in this region, especially regarding military activity. Despite the declaration of a limitless friendship with China, Russia has not provided Beijing with opportunities to conduct overt military operations directly in and around the Arctic Zone of the Russian Federation (AZRF). Compared with the growing frequency and scale of U.S. cooperation with Norway on Arctic military training and exercises, sailing a few destroyers well below the Arctic Circle pales in comparison.

I’m unsure how much a contest over military exercises tells us. Nonetheless, what’s indisputable is that China’s footprint continues to grow even if it’s not to the level of US training and exercises in Norway.

In October, for example, China’s Coast Guard entered Arctic Ocean waters for the first time as part of a joint patrol with Russia. Four vessels from the Russian Border Guard and Chinese Coast Guard were spotted by the US in the Bering Sea – the northernmost location it said it had ever observed the Chinese ships. And in July US and Canadian forces intercepted Russian and Chinese bombers flying together near Alaska for the first time.

Part of the reason for such moves is to send a message to Washington whose military activities in the South and East China Seas and arming of Taiwan are not well-received in Beijing.

Energy and the Far East

Here’s RAND on the proposed Power of Siberia 2 pipeline:

Similarly, China has not written a blank check for Russia to develop its Siberian energy reserves. To the contrary, Moscow has been unable to convince Beijing, as of the time of this publication, to fund the larger capacity Power of Siberia 2 pipeline, despite numerous meetings between these countries’ leadership. There are several potential reasons for this lack of funding: One is that China is waiting for an even better deal on energy resources; another is that Beijing could be wary of being overly dependent on Russia for energy…

Power of Siberia 2 (PS2) is a proposed pipeline that would have the capacity to carry 50 billion cubic meters per year from Russia to China, but the two sides are struggling to come to an agreement on price.

PS2 is often overblown in the Western media. While Russia has both economic and geopolitical reasons for wanting to get a deal done, it doesn’t want to give the gas away.

And China currently has other options, including pipeline gas from Central Asia and LNG suppliers such as Qatar. Its demands are currently met by existing contracts and might not need the gas from PS2 prior to the mid-2030s. It could be attractive, however, due to US efforts to control China’s rise and its energy supply and Beijing’s reluctance to rely too heavily on LNG from the likes of Australia and the US.

Less mentioned is that Russia also has options. It continues to increase LNG exports — largely to China — and has a goal to triple overall exports by 2030. China would play a huge real in achieving that goal, but that would make PS2 unlikely. Either way the gas is getting to China, and Russia is doing just fine with its energy exports:

The problem for the US is that further tightening sanctions on Russia makes Moscow more dependent on China, which benefits Beijing.

Any attempt to isolate China (say by cutting LNG from Australia and Middle East or pipelines from Central Asia) makes China more dependent on Russia.

Even without PS2 China is already getting 38 bcm through the original Power of Siberia. Starting in 2027, gas will also go to China via the Far Eastern route, which is set to have a capacity of some 10 Bcm/year. That’s 48 bcm per year is already a massive amount. A useful map from S&P Global:

With the heavy focus on PS2, RAND (and others) also miss all the other developments in Russia’s Far East. Let’s take a quick look.

Over the past ten years, Russia has laid more than 2,000 kilometers of railway tracks and renovated more than 5,000 kilometers on the Trans-Siberian Railway and the Baikal-Amur Mainline.

Russia’s Baikal-Amur Mainline: Great Nothern Railway marks its 50th anniversary

Today one of the longest railways in the world — Russia’s Baikal-Amur Mainline (BAM) — is celebrating its half-century anniversary.

BAM now largely determines global logistics for the entire 21st… pic.twitter.com/E4XkXBSJWc

— Sputnik (@SputnikInt) April 23, 2024

By the end of this year, the carrying capacity of these networks is expected to reach 180 million tonnes — an increase of 36 million since 2021. More than 3,100 kilometers of tracks are planned for the next eight years, as well, which will help Moscow meet international demand for resources from its East.

China and Russia are also working together to increase the capacity of resources heading to the former. In 2022, they opened the lone vehicle bridge crossing the Amur River, which forms more than 1,600 of their roughly 4,000 border kilometers. Later that year they opened the Tongjiang Bridge, currently the only railway bridge connecting the two countries. It shortens the journey between China’s Heilongjiang region and Moscow by more than 800 kilometers over previous routes, saving 10 hours of transit time. This helped rail transport between the two countries jump to 161 million tonnes in 2023, a 36 percent increase from 2022. Over the first five months of this year, it grew another 20 percent.

A second railway bridge over the Amur is coming soon and will provide Russia’s resource-rich Sakha Republic with direct access to China. The new route will be 2,000 kilometers shorter than the current one which involves the use of sea ports. Beijing is investing in this railway construction in the Sakha Republic as part of a new international corridor in the Russian Far East: the Mohe-Magadan railway line.

RAND wraps up its rundown of China-Russia trouble in paradise with hypotheticals that, while possible, start to sound a little desperate:

The Arctic relationship between Russia and China could be damaged by a hypothetical diplomatic clash – for instance, if China were to precipitate a major safety or environmental incident in the vicinity of the Russian Arctic or somehow publicly embarrass Moscow by undermining the perception that Russia exerts full control over its Arctic region. More broadly, some serious indications that China might represent a direct and immediate military threat to Russia in the Arctic could lead to a backlash from Moscow.

How is the US supposed to exploit these points of contention? RAND argues the following:

Western policies that focus on differences between Russia and China may ultimately be more successful in shaping the Arctic’s future than those that emphasize their similarities or their relationship itself as the primary driver of regional outcomes….

Chinese growing interest in Arctic resources does not necessarily translate to a stronger dependence on Russia alone…China’s relationship with the United States is a big influence on this scenario’s probability; six of the seven other Arctic countries (except Russia) are allies, militarily and otherwise, of the United States. This scenario would assume a reversal of these countries’ existing preference to watch closely—and deny more often than not—China’s efforts to invest in such sectors as real estate and critical technologies. This scenario also offers a reminder that although the Sino-Russian relationship is important, the mere existence of their relationship is not the only determinant to how China can potentially extend its influence in the region…

One key policy decision by the United States and its northern NATO allies could be to develop separate strategies for dealing with Moscow and Beijing when it comes to Arctic affairs.

What does that look like? Conveniently, more of the same, which means the US doesn’t have to do much of anything other than stay the course and wait:

The Western Arctic countries yield strong potential to realize their interests and diminish the power of the Sino-Russian relationship by developing policies that (1) recognize Russia as an aggressive, risk-taking, but ultimately legitimate Arctic state and (2) recognize that China has no innate influence in the Arctic and pursues a vested interest in maintaining good economic and scientific relationships with all Arctic nations. There may be no need to drive a wedge between Russia and China in the Arctic because it already exists through their differences as Arctic actors and difficult history together.

RAND, to its credit, does admit is that much of the Russian-Chinese cooperation is mutually beneficial:

…the Sino-Russian relationship is driven by Russia’s need for funding and technology to develop its Arctic region, especially because its pool of investors waned with the invasion of Ukraine and sanctions, and by China’s desire to gain a foothold in the region and tap into Russia’s hydrocarbon resources and access to the NSR for Arctic navigation.

Furthermore:

Russia and China have forged a cooperative relationship that has (at least to some measure) helped Russia to further develop its northern economy and afforded China tangible opportunities to establish itself as a recognized stakeholder in the region. The most prominent example is the investment of Chinese companies in two liquid natural gas (LNG) projects in the Yamalo- Nenets Autonomous Okrug in northern Siberia and the Power of Siberia 1 pipeline.27 Overall, China has invested billions of dollars in energy and mining projects in Russia’s Arctic, although the bulk of its investment in Russia (and across the Arctic writ large) is in Yamal LNG, which is a massive undertaking.28 In addition, the Chinese transportation company COSCO SHIPPING Lines Co., Ltd., has been exploring the use of the NSR running along Russia’s Arctic coastline as an option for future global logistics.

RAND does not, however, consider one the driving forces behind the increased cooperation: the current policy of the US and its vassals. And when you add that factor to the mix, it shows why a Moscow-Beijing split is unlikely. Even if the US and its Arctic allies try to develop separate policies for Beijing and Moscow, the latter two would still have the incentive to work together. Indeed, what makes the NSR more attractive isn’t just how short a route it is between Europe and Asia; it’s that its 5,600 kilometers are controlled by just one country (Russia), which means it faces less potential chokepoints than others.

A big part of that is because of how the West bailed on Russian Arctic projects.

Much of Russia’s plans for the extraction and delivery of its Arctic resources previously involved the West, but that, of course, is no longer the case. European shipping companies mostly cut ties with Russian operators in 2022. As part of the economic war against Russia, Western partners abandoned Northern Sea energy projects. At first, traffic fell off a cliff, but it has since rebounded and now looks set to grow exponentially into the future with both Beijing and Moscow being the biggest winners. According to Silk Road Briefing, “a central hub for building large-capacity offshore structures to produce liquefied natural gas (LNG) on a very large scale is underway based in Murmansk. Russia is active in boosting the production of sea-borne super-cooled gas as its pipeline gas exports to Europe, once a key source of revenue for Moscow, have plummeted amid the Western sanctions imposed over the conflict in Ukraine. Those resources are now being directed East, where consumer demand is far greater.”

And yet the RAND authors propose the US keep up the very policies that are driving Moscow and Beijing together in a bid to drive a wedge between them.

Loading…