“In a short time, man will be able to see what is happening anywhere in the world without leaving his own house,” the gypsy chief Melquiades prophesies to the settlers of Macondo on Page 2 of One Hundred Years of Solitude by Gabriel Garcia Marquez. Fast-forward 415 pages, and we learn that Melquiades’s chronicle of the life and death of the Buendia clan “concentrated a century of daily episodes in such a way that they coexisted in one instant.” Rewind 399 pages, and Macondo, the future lost utopia, appears in Jose Arcadio Buendia’s dreams as “a noisy city with houses having mirror walls.”

If Marquez anticipated a reality-spanning system like the internet — a total collapse of distance, a new simultaneity of everything, and a world of noise and infinite mirrors — he also didn’t think the noblest dreams of spatial, temporal, and psychic convergence could fully overcome the broken state of human affairs. We know from the family tree at the very beginning of the novel that the Buendias will die out, that their paradise will fail, and that Arcadio will not get a second opportunity on Earth.

Netflix is a Macondoesque enterprise, a promised land of infinite cultural riches that became a ruin of algorithmic middlebrow dreck. Thus, a 16-hour Netflix-produced adaptation of One Hundred Years of Solitude can only result from a farcical misunderstanding. Marquez’s masterpiece is a book about the beautiful futility of the deepest dreams of humankind, and the 1967 novel comments on the failures of the 21st-century internet in a characteristically counter-linear fashion.

Marquez understood the dangers of any adaptation of One Hundred Years of Solitude in any form and never sold the book’s film rights. Sadly, in 2014, the 87-year-old Nobelist repeated the Buendias’ mistake and died. His surviving family agreed to a Netflix series on the condition that it be shot in Spanish in Marquez’s native Colombia, with no constraint on length. The first eight episodes premiered in early December.

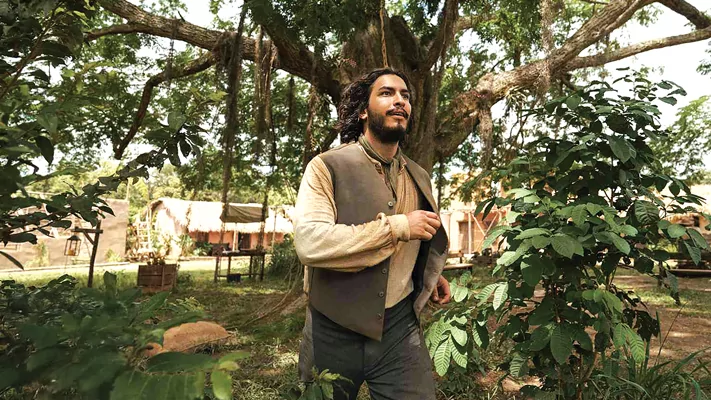

Two very different filmmakers helmed the project. The Colombian Laura Mora is best known for the 2021 film The Kings of the World, an unnerving visual poem about five Medellin street children who embark on a self-annihilating jungle quest. In contrast, the Argentinian Alex Garcia Lopez has worked on various Marvel-related television products and directed five episodes of Netflix’s widely lambasted live-action remake of Cowboy Bebop. Perhaps they are not so mismatched. Marquez was both a Mora-like mystic and a Lopezian popular storyteller. Solitude is maybe the least pretentious and referential of the great novels, and for all Marquez’s reluctance to have it filmed, it can read like a series of hyperspecific stage directions: “In the swampy streets there were the remains of furniture, animal skeletons covered with red lilies,” goes one typically vivid piece instruction to a future adapter.

Maybe Lopez and Mora were as doomed to failure as the Buendias. Great books almost never make for great films: Moby Dick, War and Peace, Middlemarch, and Don Quixote haven’t inspired anything nearly as good as The Godfather, which is based on what’s essentially a pulp novel. The Netflix Solitude’s key virtue and weakness is its dutiful following of orders, leading to a bear-hugging loyalty to the text. Lopez and Mora deserve credit for giving us a world of blood, fire, insects, and excrement. They don’t excise the novel’s perversions — amazingly, they don’t even bump Remedios Moscote’s age up to 15 — and none of Macondo’s various wars, massacres, suicides, murders, and descents into madness are expurgated for the sake of modern-day sensitives or narrative convenience. In their Macondo, the whores speak in sacred riddles, well-endowed sailors raffle off their bodies, and funeral bands oompah through drifts of raining yellow flowers. Flying carpets soar in the background but are gone after the first hour, once the disenchantment of the world gets underway.

Marquez had a talent for melodrama, and the filmmakers grasped how the novelist used an often hysterical emotional register to direct titillated readers toward his higher themes. Claudio Catano is a perfectly tortured Colonel Aureliano Buendia, constantly unsure of whether it’s impotence or injustice he’s really battling against, while Marleyda Soto embodies the doubt and resolve churning within the elderly Ursula, the book’s increasingly isolated pillar of matronly authority. The intimacy and sheer length of television allow us to see how love becomes both a prison and an escape hatch for generation after generation of Buendias. At its best, the show has the propulsion of a good anime or a Bollywood film, or perhaps a telenovela, and for about five of the eight episodes, the narrative line stays remarkably taut. For many long and satisfying stretches, there is something portentous or shocking or important happening to one of the show’s dozens of characters in seemingly every scene.

But Lopez and Mora have a reverence for Marquez that occasionally borders on fear. The constant voice-over reading entire paragraphs from the novel hints at their panic and at a secret lack of confidence that streaming television is up to the task at hand. Do we really need to hear about the “rocks like prehistoric eggs” in the Macondo riverbed when we’ve already seen them five minutes earlier? And why be told about the Arab traders with slippers on their feet and rings in their ears when it is possible to just show them? A better and more daring adaptation would have had no voice-over at all. Marquez’s text becomes a crutch for the filmmakers, a way of avoiding the difficulties of manifesting the novel’s deepest, most elusive qualities.

Creatively paralyzed with the dread of desecrating its source material, the show follows an unfortunately strict adherence to the linear chronology of events in a decidedly nonlinear novel — “The world was so recent that many things lacked names,” begins the biblical third sentence of Solitude, which on Netflix isn’t read to us via voice-over until 95 minutes in. The show eats runtime with extraneous battle scenes, slow-motion shots, and longer-than-necessary treatments of minor characters, though fans of the arch-bureaucrat Apolinar Moscote and the left-wing terrorist Dr. Noguera will not be disappointed.

CLICK HERE TO READ MORE FROM THE WASHINGTON EXAMINER

Solitude is the greatest novel of the postwar period because it is simultaneously the story of a family, the nation of Colombia, the book of Genesis, and the entire human race. It is unforgettable because it makes its readers feel the weight and wonder of passing time and all that it contains. Much of the pleasure and sadness of the book emerges from the tension between its vast scope and its brisk pace, but events that flash by in a paragraph drag for 20 minutes onscreen. The Netflix Solitude is weighty more often than wondrous.

The last eight hours of the Netflix series haven’t been released yet — by my count, we’re only up to page 150 or so out of 417 — and while its first half is frequently excellent, I imagine a lot of viewers will finish the series not with tears in their eyes, but with relief.

Armin Rosen is a New York-based reporter at large for Tablet.