Authored by Francis P. Sempa via RealClearDefense,

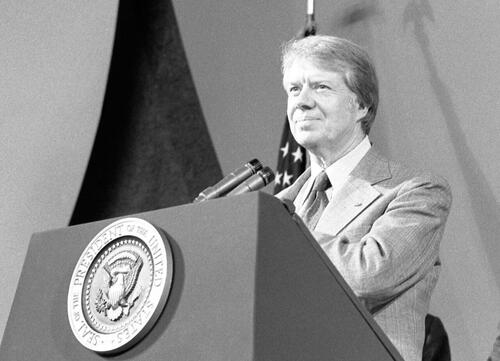

Tom Donilon, President Barack Obama’s national security adviser from 2010 to 2013, attempts to rewrite history on the Foreign Affairs website to praise Jimmy Carter as a great foreign policy president. We “learn” from Donilon that Carter left a legacy of peace in the Middle East with the Camp David Accords, enhanced U.S. security in the broader Persian Gulf region by proclaiming the Carter Doctrine, deftly managed our relationship with China by advancing the “one China” policy and ensured the ultimate downfall of the Soviet Union. One wonders why American voters overwhelmingly rejected Carter in 1980 after he accomplished so much (according to Donilon).

There was a time when Democrats had the courage to distance themselves from a failed foreign policy by a president of their own party—and that time was in the late 1970s. The list of prominent Democrats who supported GOP candidate Ronald Reagan over Carter in the 1980 election because of Carter’s failed foreign policy was long and distinguished, and included the likes of Paul Nitze, Jeane Kirkpatrick, Max Kampelman, Norman Podhoretz, Lane Kirkland, Eugene Rostow, Richard Perle, Richard Pipes, and Elliot Abrams, among others. Many of these were known then as “Scoop Jackson Democrats,” named after the long-serving Senator from the state of Washington Henry M. Jackson, a key member of the Armed Services Committee. Scoop Jackson was one of the nation’s chief critics of détente, especially as practiced by the Carter administration. Scoop Jackson was on Reagan’s transition team. Kirkpatrick, Rostow, Perle, Abrams, Pipes and Nitze all joined Reagan’s national security team.

The first major Democratic salvo against Carter’s foreign policy was fired by Jeane Kirkpatrick in an article in Commentary in 1979 titled “Dictatorships and Double Standards.” Kirkpatrick’s first sentence set the theme of the article: “The failure of the Carter administration’s foreign policy is now clear to everyone except its architects, and even they must entertain private doubts, from time to time, about a policy whose crowning achievement has been to lay the groundwork for a transfer of the Panama Canal from the United States to a swaggering Latin dictator of Castroite bent.” Kirkpatrick criticized Carter for failing to adequately respond to a massive Soviet conventional and military build-up, watching as the Soviets extended their political influence in Africa, Afghanistan, and the Caribbean Sea, and undermining long-time U.S. allies in Nicaragua and Iran to the detriment of U.S. security interests. Carter, she said, wielded the cudgel of “human rights” against America’s allies regardless of the strategic consequences.

But even before Kirkpatrick’s article, Carter set the theme of his approach to foreign policy in an address at Notre Dame early in his presidency, when he proclaimed that he “believe[d] in détente with the Soviet Union,” and apologized for “abandoning our own values” for those of our adversaries. (The Obama administration, when Donilon was deputy national security adviser, infamously engaged in its own “apology tour”). Carter then uttered a line that wins the prize for foreign policy naivete: “Being confident of our own future, we are now free of that inordinate fear of communism which once led us to embrace any dictator who joined us in that fear.” The Soviets, the Sandinistas in Nicaragua, and the mullahs in Iran, as well as our allies, were undoubtedly listening.

Carter also ordered the removal of U.S. nuclear weapons from South Korea, then announced his intention to withdraw all U.S. ground forces from South Korea. “Carter made these decisions,” Steven Hayward noted, “without any consultation with the Pentagon, congressional leaders, the South Koreans, or any other U.S. allies, most notably Japan, which was shocked by Carter’s decision.” Carter was forced to abandon these decisions by public outcry from military leaders and members of congress. He followed that up by cutting the defense budget (which had been declining since the end of the Vietnam War) by $6 billion. Later, when Carter signed the SALT II Treaty with the Soviets, leading Democratic Senators, including Scoop Jackson and Daniel Patrick Moynihan, opposed ratification, which forced Carter to withdraw the treaty from consideration.

The next major salvo came from Commentary’s editor Norman Podhoretz in his small but influential book The Present Danger. Podhoretz characterized Carter’s foreign policy as “strategic retreat” which involved a “steady process of accommodation to Soviet wishes and demands.” He noted that Carter’s Secretary of State Cyrus Vance stated that the United States and Soviet Union had “similar dreams and aspirations.” Arms control became the centerpiece of Carter’s defense policy as he “delay[ed] or cancel[ed] production of one new weapons system after another—the B-1 bomber, the neutron bomb, the MX, the Trident—while the Soviet Union went on increasing and refining its arsenal.” When Carter did nothing to prevent the fall of the Shah in Iran (despite being urged to do something by National Security Adviser Zbigniew Brzezinski), the administration characterized the non-response as “mature restraint” (and Carter’s UN Ambassador Andrew Young called Ayatollah Khomeini a “saint”) but Podhoretz more accurately called it a “culture of appeasement.” We have been dealing with the consequences of Carter’s “mature restraint” for 45 years.

When the Soviet Union invaded Afghanistan, Carter expressed surprise that the Kremlin would invade another country. The reality of Soviet perfidy caused Carter to reverse course to an extent (which Donilon emphasizes in his article), but by then it was too late. A disastrous failed rescue attempt of the American hostages in Iran came to symbolize Carter’s entire foreign policy.

Donilon is wrong in every aspect of his praise for Carter. The success of the Camp David Accords (for which Nixon, Ford, and Kissinger had laid the groundwork) pales in comparison to the loss of Iran as a strategic ally in the region. Carter’s “management” of China needn’t have included ending formal relations with Taiwan (and Carter only reluctantly signed the Tawain Relations Act which was championed by GOP Senator Barry Goldwater). Donilon’s claim that Carter ensured the downfall of the Soviet Union is, frankly, laughable. Carter was in the process of losing the Cold War when the voters kicked him out of office in favor of Ronald Reagan—who, contrary to Donilon, deserves the most credit for winning the Cold War.

As Steven Hayward noted in The Age of Reagan, “It is difficult to understate the completeness of the disaster of Carter’s presidency.” Hayward judged Carter’s foreign policy even more disastrous than his domestic policy which saw the dangerous rise of the economic “misery index.” “Carter came to be regarded, Hayward wrote, “as the American Neville Chamberlain” who demonstrated a “general incapacity to perceive and act according to the geopolitical realities of the moment.” That, not Tom Donilon’s fairy tale, is Carter’s true foreign policy legacy.

Francis P. Sempa writes on foreign policy and geopolitics. His Best Defense columns appear at the beginning of each month.

Authored by Francis P. Sempa via RealClearDefense,

Tom Donilon, President Barack Obama’s national security adviser from 2010 to 2013, attempts to rewrite history on the Foreign Affairs website to praise Jimmy Carter as a great foreign policy president. We “learn” from Donilon that Carter left a legacy of peace in the Middle East with the Camp David Accords, enhanced U.S. security in the broader Persian Gulf region by proclaiming the Carter Doctrine, deftly managed our relationship with China by advancing the “one China” policy and ensured the ultimate downfall of the Soviet Union. One wonders why American voters overwhelmingly rejected Carter in 1980 after he accomplished so much (according to Donilon).

There was a time when Democrats had the courage to distance themselves from a failed foreign policy by a president of their own party—and that time was in the late 1970s. The list of prominent Democrats who supported GOP candidate Ronald Reagan over Carter in the 1980 election because of Carter’s failed foreign policy was long and distinguished, and included the likes of Paul Nitze, Jeane Kirkpatrick, Max Kampelman, Norman Podhoretz, Lane Kirkland, Eugene Rostow, Richard Perle, Richard Pipes, and Elliot Abrams, among others. Many of these were known then as “Scoop Jackson Democrats,” named after the long-serving Senator from the state of Washington Henry M. Jackson, a key member of the Armed Services Committee. Scoop Jackson was one of the nation’s chief critics of détente, especially as practiced by the Carter administration. Scoop Jackson was on Reagan’s transition team. Kirkpatrick, Rostow, Perle, Abrams, Pipes and Nitze all joined Reagan’s national security team.

The first major Democratic salvo against Carter’s foreign policy was fired by Jeane Kirkpatrick in an article in Commentary in 1979 titled “Dictatorships and Double Standards.” Kirkpatrick’s first sentence set the theme of the article: “The failure of the Carter administration’s foreign policy is now clear to everyone except its architects, and even they must entertain private doubts, from time to time, about a policy whose crowning achievement has been to lay the groundwork for a transfer of the Panama Canal from the United States to a swaggering Latin dictator of Castroite bent.” Kirkpatrick criticized Carter for failing to adequately respond to a massive Soviet conventional and military build-up, watching as the Soviets extended their political influence in Africa, Afghanistan, and the Caribbean Sea, and undermining long-time U.S. allies in Nicaragua and Iran to the detriment of U.S. security interests. Carter, she said, wielded the cudgel of “human rights” against America’s allies regardless of the strategic consequences.

But even before Kirkpatrick’s article, Carter set the theme of his approach to foreign policy in an address at Notre Dame early in his presidency, when he proclaimed that he “believe[d] in détente with the Soviet Union,” and apologized for “abandoning our own values” for those of our adversaries. (The Obama administration, when Donilon was deputy national security adviser, infamously engaged in its own “apology tour”). Carter then uttered a line that wins the prize for foreign policy naivete: “Being confident of our own future, we are now free of that inordinate fear of communism which once led us to embrace any dictator who joined us in that fear.” The Soviets, the Sandinistas in Nicaragua, and the mullahs in Iran, as well as our allies, were undoubtedly listening.

Carter also ordered the removal of U.S. nuclear weapons from South Korea, then announced his intention to withdraw all U.S. ground forces from South Korea. “Carter made these decisions,” Steven Hayward noted, “without any consultation with the Pentagon, congressional leaders, the South Koreans, or any other U.S. allies, most notably Japan, which was shocked by Carter’s decision.” Carter was forced to abandon these decisions by public outcry from military leaders and members of congress. He followed that up by cutting the defense budget (which had been declining since the end of the Vietnam War) by $6 billion. Later, when Carter signed the SALT II Treaty with the Soviets, leading Democratic Senators, including Scoop Jackson and Daniel Patrick Moynihan, opposed ratification, which forced Carter to withdraw the treaty from consideration.

The next major salvo came from Commentary’s editor Norman Podhoretz in his small but influential book The Present Danger. Podhoretz characterized Carter’s foreign policy as “strategic retreat” which involved a “steady process of accommodation to Soviet wishes and demands.” He noted that Carter’s Secretary of State Cyrus Vance stated that the United States and Soviet Union had “similar dreams and aspirations.” Arms control became the centerpiece of Carter’s defense policy as he “delay[ed] or cancel[ed] production of one new weapons system after another—the B-1 bomber, the neutron bomb, the MX, the Trident—while the Soviet Union went on increasing and refining its arsenal.” When Carter did nothing to prevent the fall of the Shah in Iran (despite being urged to do something by National Security Adviser Zbigniew Brzezinski), the administration characterized the non-response as “mature restraint” (and Carter’s UN Ambassador Andrew Young called Ayatollah Khomeini a “saint”) but Podhoretz more accurately called it a “culture of appeasement.” We have been dealing with the consequences of Carter’s “mature restraint” for 45 years.

When the Soviet Union invaded Afghanistan, Carter expressed surprise that the Kremlin would invade another country. The reality of Soviet perfidy caused Carter to reverse course to an extent (which Donilon emphasizes in his article), but by then it was too late. A disastrous failed rescue attempt of the American hostages in Iran came to symbolize Carter’s entire foreign policy.

Donilon is wrong in every aspect of his praise for Carter. The success of the Camp David Accords (for which Nixon, Ford, and Kissinger had laid the groundwork) pales in comparison to the loss of Iran as a strategic ally in the region. Carter’s “management” of China needn’t have included ending formal relations with Taiwan (and Carter only reluctantly signed the Tawain Relations Act which was championed by GOP Senator Barry Goldwater). Donilon’s claim that Carter ensured the downfall of the Soviet Union is, frankly, laughable. Carter was in the process of losing the Cold War when the voters kicked him out of office in favor of Ronald Reagan—who, contrary to Donilon, deserves the most credit for winning the Cold War.

As Steven Hayward noted in The Age of Reagan, “It is difficult to understate the completeness of the disaster of Carter’s presidency.” Hayward judged Carter’s foreign policy even more disastrous than his domestic policy which saw the dangerous rise of the economic “misery index.” “Carter came to be regarded, Hayward wrote, “as the American Neville Chamberlain” who demonstrated a “general incapacity to perceive and act according to the geopolitical realities of the moment.” That, not Tom Donilon’s fairy tale, is Carter’s true foreign policy legacy.

Francis P. Sempa writes on foreign policy and geopolitics. His Best Defense columns appear at the beginning of each month.

Loading…