Authored by Doug O'Laughlan via 'Fabricated Knowledge' substack,

One of my favorite market sayings is that “narrative follows price.” In the case of DeepSeek, this has never been truer. I’ll summarize the high-level points of DeepSeek and, importantly, discuss where we are in the vibes cycle.

DeepSeek is hilarious to me because of how it contrasts with literally one month ago.

One month ago, around the time of Neurips, the prevailing narrative was that pretraining scaling laws were slowing.

Therefore, continued investment in AI infrastructure would slow down as incremental spending on new equipment wouldn’t justify the return.

SemiAnalysis did a fantastic job explaining why that wouldn’t be the case. Ironically, Reinforcement learning and continued architectural progress were some of the main reasons. Pretraining was slowing down, and thus, GPU demand was “over.”

Now fast forward to DeepSeek, which released their reasoning model a week ago, on January 20th, 2025, and v3, their much smaller model, on December 26th, 2024. For those closely watching, I believe that X was all over the concept of “intelligence too cheap to meter,” but then the narrative took a turn for the wilder on Friday and into the weekend.

What is so startling here is how both are perceived as bad for infrastructure spending, yet the latter refutes the former. Now, algorithmic progress is so significant that we will not need to build any new infrastructure. Technology has improved, but demand is impaired. The reality, of course, is somewhere between these two extremes because they both cannot be accurate and are inadequate for GPU demand. You can’t tell me an algorithmic improvement from a Chinese company that the market was begging for last quarter is now doomed.

The reality is that this market is heated and is looking for a reason to sneeze. I hate to be cliche and call Mr. Market bipolar, but it truly is. This is just the latest wall of worry for AI companies to climb. Let’s discuss the bull and the bear debate, and then I’ll discuss where I think it’s going.

Jevons Paradox (Bull Case)

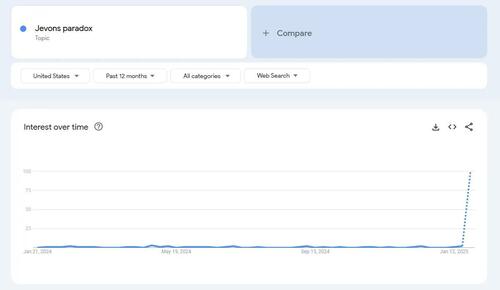

This phrase might be new to you, but I think today is the day it crosses over into the mainstream lexicon. Just look at search interest right now. I believe Cathie of Arkk Invest made it popular, but today, it’s the rallying cry of bulls.

So what is the Jevons Paradox? It’s pretty much the observation that technology does make a good cheaper; what happens is that the demand for the good paradoxically increases. There are a few notable examples, and my favorite one, of course, is transistors. Transistors got cheaper every year for 50 years, and ironically, instead of needing less every year, we used much more, even accounting for shrink. If the price of a flight dropped from 1000s to 10s of dollars, I would probably fly more.

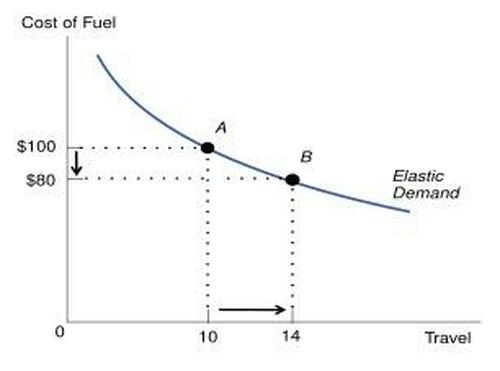

Think of it this way: if it’s cheaper, you’d use more of it, which is the definition of elastic demand and a good candidate for the Jevon Paradox.

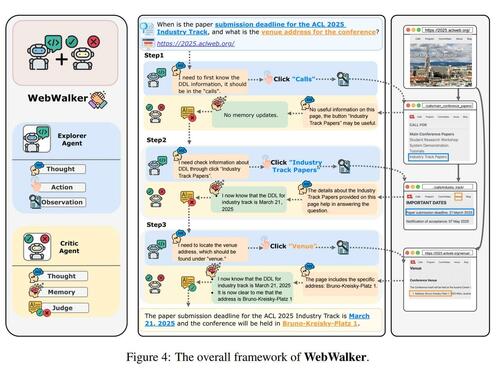

Now, let’s use the context of AI. This is WebwalkerQA (this is not even a useful paper), but I was looking at WebWalkerQA, and they gave an example of two agentic AIs that searched websites together to provide better information.

If the cost of agents was lower, why stop at two? A friend remarked that your intelligent coffee machine could have a million Einsteins working on making the best cup of coffee every day. As intelligence gets cheaper, we will throw more brute-force intelligence at every one of the world’s key problems. In a world with massively lower costs, instead of becoming more efficient, we often throw more resources at the problem.

This is the thrust of the Jevons Paradox as a bull case and what will almost assuredly happen in the long run. It took ~16,000 transistors to get a rocket on the moon. Now, ~16,000 transistors probably could run any modern application. What becomes cheaper gets used more, and ironically, demand explodes.

Supply Overshoots Demand and Timeline

There is one little problem - and one I’ve been writing about in my recent piece on capital cycles. Lead and lagging times can create kinks, producing very drastic scenarios. Maybe the Jevon paradox is correct, but the issue is not if we will use more, but a bit about timing.

What happens if the deflator of 90% better models massively outweighs the increased usage? There’s a pertinent case study: DWDM (Dense wavelength-division multiplexing) massively increases the fiber supply. And so, while the Jevons paradox case was 100% correct in the long run, 97% of the fiber laid in 2001 was unlit. Most of that fiber is now lit today, but Jevons paradox can be long run right and in the short run the companies are entirely divorced from reality.

That is an example of a supply-and-demand overshoot that the market is quickly contemplating. The terminal value is acceptable for everyone involved, but the pesky short run escapes us.

In this case, the bear case is that yes, Jevons happens, but supply overwhelms demand so much in the short term that the rapid addition of supply overwhelms the long-term demand.

The reality is likely never as bad as feared and never as good as dreamed.

Authored by Doug O’Laughlan via ‘Fabricated Knowledge’ substack,

One of my favorite market sayings is that “narrative follows price.” In the case of DeepSeek, this has never been truer. I’ll summarize the high-level points of DeepSeek and, importantly, discuss where we are in the vibes cycle.

DeepSeek is hilarious to me because of how it contrasts with literally one month ago.

One month ago, around the time of Neurips, the prevailing narrative was that pretraining scaling laws were slowing.

Therefore, continued investment in AI infrastructure would slow down as incremental spending on new equipment wouldn’t justify the return.

SemiAnalysis did a fantastic job explaining why that wouldn’t be the case. Ironically, Reinforcement learning and continued architectural progress were some of the main reasons. Pretraining was slowing down, and thus, GPU demand was “over.”

Now fast forward to DeepSeek, which released their reasoning model a week ago, on January 20th, 2025, and v3, their much smaller model, on December 26th, 2024. For those closely watching, I believe that X was all over the concept of “intelligence too cheap to meter,” but then the narrative took a turn for the wilder on Friday and into the weekend.

What is so startling here is how both are perceived as bad for infrastructure spending, yet the latter refutes the former. Now, algorithmic progress is so significant that we will not need to build any new infrastructure. Technology has improved, but demand is impaired. The reality, of course, is somewhere between these two extremes because they both cannot be accurate and are inadequate for GPU demand. You can’t tell me an algorithmic improvement from a Chinese company that the market was begging for last quarter is now doomed.

The reality is that this market is heated and is looking for a reason to sneeze. I hate to be cliche and call Mr. Market bipolar, but it truly is. This is just the latest wall of worry for AI companies to climb. Let’s discuss the bull and the bear debate, and then I’ll discuss where I think it’s going.

Jevons Paradox (Bull Case)

This phrase might be new to you, but I think today is the day it crosses over into the mainstream lexicon. Just look at search interest right now. I believe Cathie of Arkk Invest made it popular, but today, it’s the rallying cry of bulls.

So what is the Jevons Paradox? It’s pretty much the observation that technology does make a good cheaper; what happens is that the demand for the good paradoxically increases. There are a few notable examples, and my favorite one, of course, is transistors. Transistors got cheaper every year for 50 years, and ironically, instead of needing less every year, we used much more, even accounting for shrink. If the price of a flight dropped from 1000s to 10s of dollars, I would probably fly more.

Think of it this way: if it’s cheaper, you’d use more of it, which is the definition of elastic demand and a good candidate for the Jevon Paradox.

Now, let’s use the context of AI. This is WebwalkerQA (this is not even a useful paper), but I was looking at WebWalkerQA, and they gave an example of two agentic AIs that searched websites together to provide better information.

If the cost of agents was lower, why stop at two? A friend remarked that your intelligent coffee machine could have a million Einsteins working on making the best cup of coffee every day. As intelligence gets cheaper, we will throw more brute-force intelligence at every one of the world’s key problems. In a world with massively lower costs, instead of becoming more efficient, we often throw more resources at the problem.

This is the thrust of the Jevons Paradox as a bull case and what will almost assuredly happen in the long run. It took ~16,000 transistors to get a rocket on the moon. Now, ~16,000 transistors probably could run any modern application. What becomes cheaper gets used more, and ironically, demand explodes.

Supply Overshoots Demand and Timeline

There is one little problem – and one I’ve been writing about in my recent piece on capital cycles. Lead and lagging times can create kinks, producing very drastic scenarios. Maybe the Jevon paradox is correct, but the issue is not if we will use more, but a bit about timing.

What happens if the deflator of 90% better models massively outweighs the increased usage? There’s a pertinent case study: DWDM (Dense wavelength-division multiplexing) massively increases the fiber supply. And so, while the Jevons paradox case was 100% correct in the long run, 97% of the fiber laid in 2001 was unlit. Most of that fiber is now lit today, but Jevons paradox can be long run right and in the short run the companies are entirely divorced from reality.

That is an example of a supply-and-demand overshoot that the market is quickly contemplating. The terminal value is acceptable for everyone involved, but the pesky short run escapes us.

In this case, the bear case is that yes, Jevons happens, but supply overwhelms demand so much in the short term that the rapid addition of supply overwhelms the long-term demand.

The reality is likely never as bad as feared and never as good as dreamed.

Loading…