The first time we went hiking in Wyoming’s Grand Teton National Park, we were advised to sing our way through the woods and across the mountain streams. The point was to communicate to the bears that you were approaching since there a few things less pleasant than surprising a bear in the wild.

Jerome Powell likely arrived this week in Jackson Hole, Wyoming, where the Kansas City Fed has held an annual economic symposium since 1982, worried that he may not have been singing quite loud enough. The market seems to not really appreciate the gravity of the Fed’s task despite repeated statements from Powell and leaders of the central bank. Will surprised bears attack when Powell appears on stage Friday?

Powell has supposedly been making hawkish speeches on interest rates and inflation since late last year, when he belatedly came around to the view that inflation was not transitory and that the deflationary forces he cited in his 2021 speech at Jackson Hole had quietly sneaked off into the netherworld. And the Fed has followed his words up with real actions, including two 75-basis point interest rate hikes and the launch of quantitative tightening.

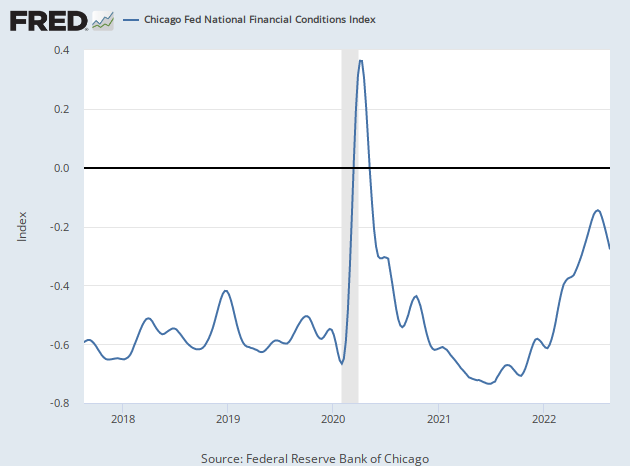

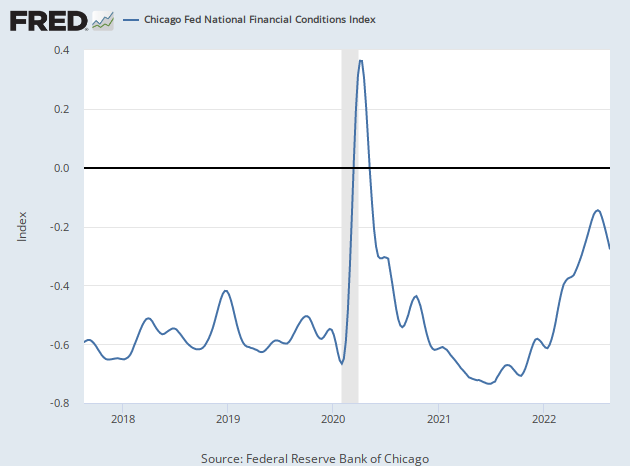

Yet the market remains decidedly unconvinced. The Chicago Fed’s National Financial Conditions Index—which looks at financial conditions in money markets, debt and equity markets, and the traditional and “shadow” banking systems—has been loosening every week since the first of July. The index remains in negative territory, which is historically associated with looser-than-average financial conditions. That is not consistent with inflation declining or the labor market cooling off.

Does the market have reason to be skeptical of the Fed’s dedication to the proposition that inflation must be brought down to two percent? We think it does. In the first place, it has been a great many years since Fed officials have seriously confronted a wave of inflation as persistent, widespread, and deep as this one. Inflation is everywhere you look in the economy and even after the Consumer Price Index (CPI) held steady in July, on year-0ver-year basis consumer prices were up 8.5 percent—the most in over 40 years.

None of the current leadership of the Fed has any experience fighting inflation. They have history books about inflation and a sort of folk memory of what it took back in the days when Paul Volcker was smoking cigars in Congressional hearings and speaking like a mysterious oracle in an ancient Attic temple. Powell has insisted that the Fed’s tools are adequate to the task of taming inflation, but the tools are largely untested. Quite literally, the “tools”—basically, communication, interest rate targeting, and shrinking the balance sheet—are untested. Volcker targeted monetary aggregates, letting interest rates rise to where the market saw fit given the supply of money the Fed was willing to supply. He did not release projections every other meeting, and the theory that expectations controlled actual inflation was still in its infancy. Quantitative easing was undreamed of, so there was no question of quantitative tightening.

Federal Reserve Chairman Paul Volcker speaking at a Congressional Domestic Policy Subcommittee on Capitol Hill on November 1, 1980. (Diana Walker/Getty Images)

They also have never had to raise rates into a recession and rising unemployment, as the Fed will almost certainly find itself having to do some time over the next year. Many investors think that Fed will not be willing to continue to turn the screws on the economy while millions are tossed out of their jobs and the mild economic contraction we saw in the first half of this year becomes a full-blown and undisputed recession. That is largely why so many investors still think the Fed will pivot to rate cuts at some point next year—even though multiple Fed officials have said they regard it as unlikely that they would flip from hiking to cutting rates. Investors do not think the Fed is play-acting: they just do not think that Fed officials know what’s coming.

A big part of Powell’s task in Jackson Hole on Friday will be to convince the market not only that he has the resolve but that he properly understands what that will cost the economy. If he continues to insist that the economy has anything but the slimmest chance of avoiding a recession, that will be taken as a dovish stance. The talk of soft-landing should be banished to wherever they sent the word transitory. He would be well-advised to remind the market that he is aware that “stop and go” stabilization policy in the 1950s and early 1960s triggered a period of instability, with the economy oscillating between recession and growth above six percent—a topic he talked about in his 2019 Jackson Hole speech.

Federal Reserve Board Chairman Jerome Powell speaks at news conference after a Federal Open Market Committee meeting on January 29, 2020, in Washington, DC. (Samuel Corum/Getty Images)

If Powell really wants to shift the market’s impression he could indicate a familiarity with the argument of Agustín Carstens, general manager of the Bank for International Settlements, that the era of weak inflation is over. “We may be on the cusp of a new inflationary era. The forces behind high inflation could persist for some time. New pressures are emerging, not least from labor markets, as workers look to make up for inflation-induced reductions in real income,” Carstens said in a speech back in April. More recently, at a gathering of central bankers in Portugal, European Central Bank President Christine Lagarde said, “I don’t think that we are going to go back to that environment of low inflation.” Powell could acknowledge the return of strong inflationary forces while reiterating his conviction that he can bring inflation down to two percent.

When you are hiking around Jackson Hole, it is not just advisable to sing but to be prepared for a confrontation with bear spray, just in case. Powell needs to show the market that he is carrying spray—or something stronger—and is not afraid of the bears.