Most obituaries for Ashton B. Carter prominently credited the former Pentagon chief with removing the last barriers to women serving in combat and allowing transgender troops to serve openly.

But long before he was former President Barack Obama’s last defense secretary, Carter was a Harvard- and Oxford-educated physicist whose expertise was in nuclear weapons policy and, in particular, dealing with the Soviet Union.

Carter died Oct. 24 at his home in Boston at the age of 68 after suffering “a sudden cardiac event,” according to his family.

FORMER DEFENSE SECRETARY ASH CARTER DIES AT AGE 68

By the time Carter came to helm the Pentagon in February 2015, he had a lot of firsthand experience with the Russians. It dated back to the 1980s, when he first began traveling to Moscow with various U.S. government and military delegations.

While an assistant defense secretary in the 1990s, Carter recalled sitting in on a summit with the new president of post-Soviet Russia, Boris Yeltsin. There, Carter spotted a “young Russian staff member sitting with his back to the wall, taking detailed notes of everything that was said and done.”

That “then-little-known security officer,” Carter recounted in his 2019 memoir Inside the Five-Sided Box, was “named Vladimir Putin.”

I first met Carter in 1994, three years after the fall of the Soviet Union as a reporter covering a trip to Pervomaysk, Ukraine, by Defense Secretary William Perry. The Pentagon chief, whose delegation included Carter, was there to witness the dismantling of SS-19 intercontinental ballistic missiles that had been part of the old Soviet arsenal.

Carter was then the assistant secretary of defense for international security policy, in charge of the Nunn-Lugar program that used U.S. tax dollars to pay for the removal of nuclear weapons from Ukraine, Kazakhstan, and Belarus.

Two years later, we went back to see the missile field that once targeted U.S. cities gone, replaced by sunflowers being planted by a landscaping crew.

It was a heady time when Carter thought the world was becoming a safer place.

“It was a profound moment because it demonstrated that the world could change for the better,” Carter wrote in his memoir. “Despite the deep-seated insecurities and fears felt by all people in a dangerous world, nations can willingly give up the awesome destructive power of nuclear weapons, placing their trust instead in a world order dedicated to peace and a powerful America dedicated to international partnerships.”

Two decades later, Ukraine would discover with Russia’s illegal annexation of Crimea that the security guarantees provided by the United States, Great Britain, and Russia in exchange for denuclearization were worthless.

And by the time Carter became Obama’s defense secretary in 2014, he would come to see Putin as a resentful man — one with dangerous dreams of becoming a modern-day czar ruling over a reconstituted Russian empire.

“In my view, Putin is a man consumed by three bitter beliefs: that the end of the Cold War was not a rebirth for Russia and its people but a humiliation; that the United States had made a mess of things by destabilizing countries and unhorsing their leaders, and would do the same to Russia and him if it could; and that, therefore, thwarting the United States around the world must be a central objective of Russian foreign policy,” Carter said in his memoir.

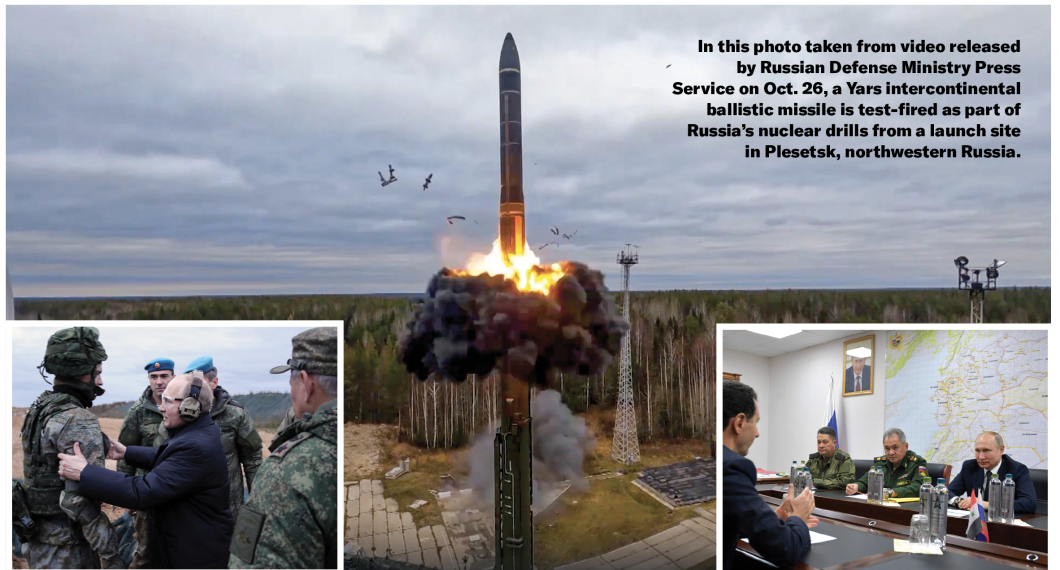

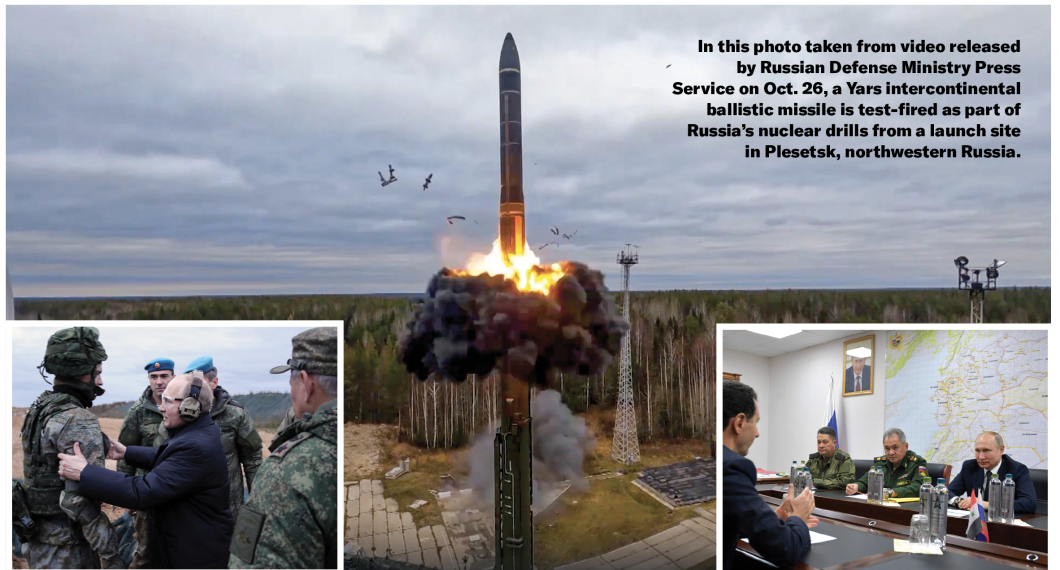

Carter warned presciently that Putin’s intimidation tactics (staging snap war games aimed at striking strike fear into Sweden, Finland, and the Baltic states, along with the aggressive overhaul of his nuclear arsenal) posed “a serious political and military threat to the democracies of the West.”

Carter wanted all new war plans drawn up to prepare for a Russian invasion or a cyberattack on NATO’s “expanded and exposed eastern flank,” particularly in the Baltics.

“Not everyone in the White House shared my concerns about Russia,” he wrote. “There were some in the Obama administration, as there had been in the Bush administration, who didn’t want to bear the political burden of developing these new war plans for Europe. Doing so required us to admit that the relationship with Russia had become largely antagonistic rather than cooperative.”

Carter said when he met one-on-one with Obama (who in 2014, after Russia annexed Crimea, dismissed Russia as a “regional power”), the president shared his concerns about Putin.

But when, in 2015, the White House drew up a strategy that specifically said Russia was “not an existential threat” to the U.S., that was something Carter said he missed in his haste to review the document.

“This was factually nonsensical: How could a country with many thousands of nuclear weapons trained on the United States not be an existential threat?” Carter wrote.

“The president supported all the increases in spending and deployment I called for. But I was the only senior member of the administration actually describing the policy the president’s actions reflected and its strategic rationale.”

Carter writes that the Obama administration’s “less-than-wholehearted pushback against Russian aggression” almost led to disaster in Syria.

His book is particularly critical of then-Secretary of State John Kerry, who also downplayed the threat from Russia and who was given the task by Obama of trying to cut a deal with Moscow to ease Syrian dictator Bashar Assad out of power and then secure a ceasefire.

Carter was highly skeptical about any prospect of working with Russia on Syria.

CLICK HERE TO READ MORE FROM THE WASHINGTON EXAMINER

“When the crafty Russian Foreign Minister Sergei Lavrov began talking to John Kerry about the possibility of ‘cooperating’ with Russia militarily in Syria, I smelled a trap,” he wrote.

“I had some sharp debates on this issue with John Kerry,” Carter wrote. “I admired his efforts to get Russia on a more constructive path, but I believed his diplomatic effort to forge a Syria cooperation pact was doomed from the start.”

Turns out he was right.