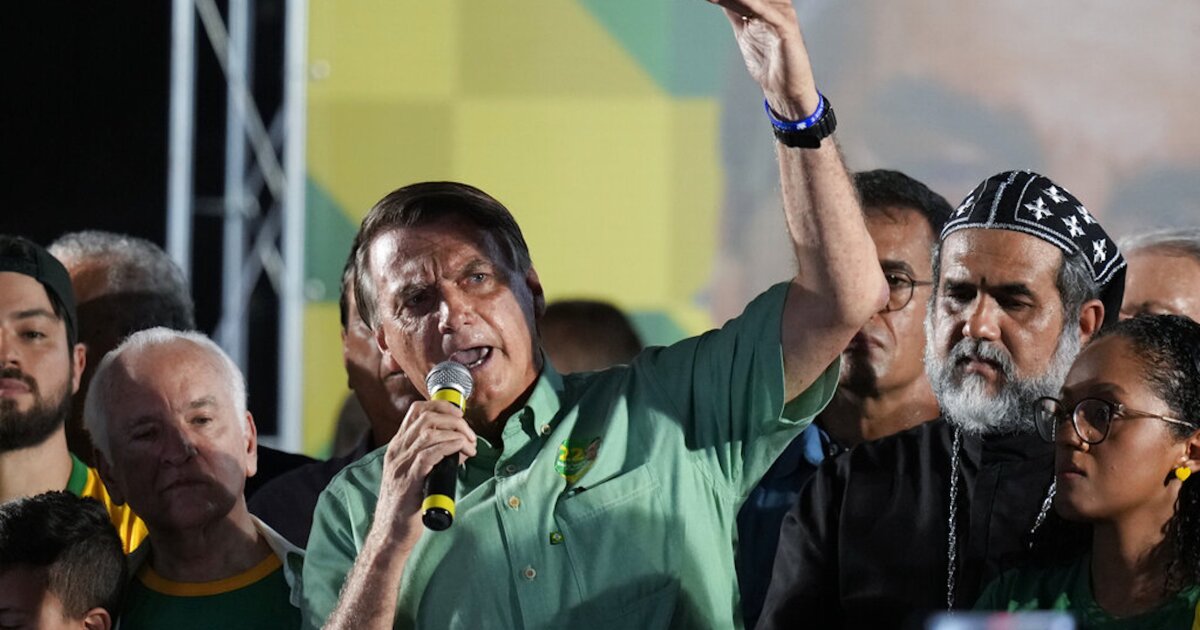

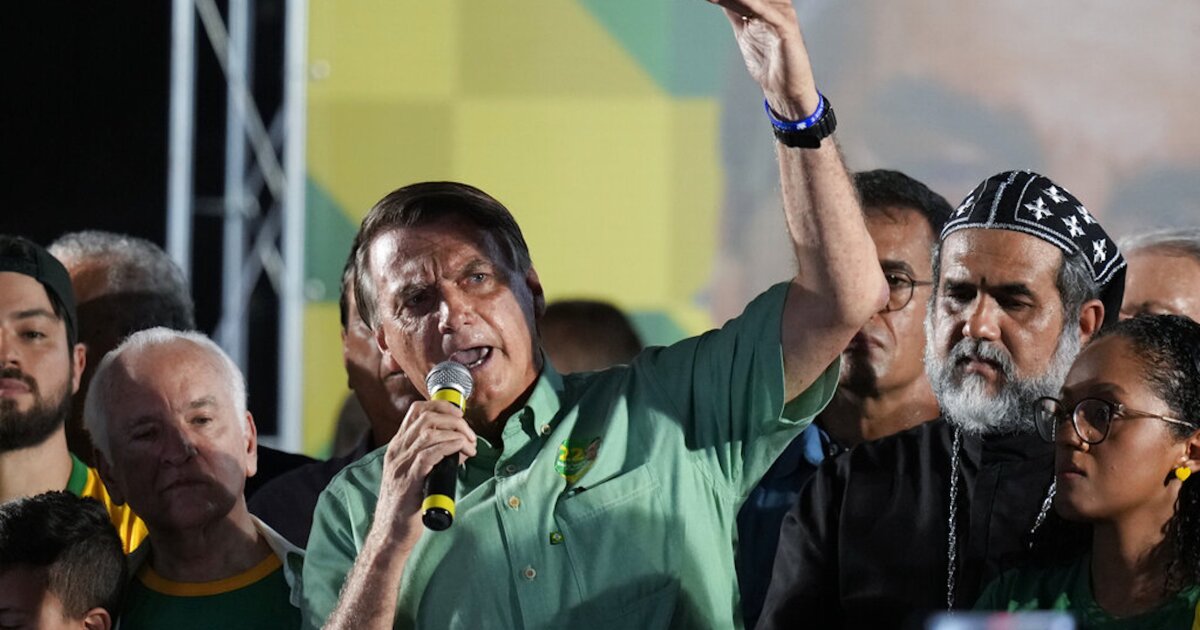

Brazilian President Jair Bolsonaro’s ability to contest the results of his country‘s presidential election has been limited by a series of warnings from key institutions and leaders of his own political coalition.

“Conservative allies of Bolsonaro and key congressional allies from other parties have either come out and recognized the results — including pro-Bolsonaro gubernatorial candidates — or seem to be pressuring him in that direction,” the Heritage Foundation’s Mateo Haydar said. “Because they did well overall.”

Bolsonaro laid the groundwork to challenge the results by alleging prior to the election that the voting machines are “completely vulnerable” to fraud — a preemptive rhetorical strike widely perceived as an imitation of former President Donald Trump’s attempt to stay in office after President Joe Biden’s victory in the 2020 presidential election. Bolsonaro’s party backed the maneuver prior to the election, but key power brokers have broken ranks in the hours since Brazilian election authorities declared that former president Luiz Inacio Lula da Silva won the election with 50.9% of the vote.

“The will of the majority, expressed at the polls, should never be challenged,” Brazil’s house speaker, Arthur Lira, a Bolsonaro ally, said Monday.

BIDEN CONGRATULATES LULA ON BEING ELECTED BRAZIL’S PRESIDENT

That statement reinforced a public message from Senate President Rodrigo Pacheco, who has spoken on behalf of a group of lawmakers and officials who coordinated throughout the election to affirm the Brazilian judiciary’s credibility as an overseer of the elections. Their voices helped fill the silence left by Bolsonaro, who made no public statement on election night and left his country in suspense through Monday.

“It was very important the speeches that were given by the heads of the Senate and the [lower house of] Congress because they were also very institutional,” a senior international organization official following the Brazilian elections told the Washington Examiner. “So that reduces the possibility of him doing anything other than conceding — if not conceding, then at least not contesting.”

Their statements presented a contrast with the preelection tactics of Bolsonaro and his party, who argued in various ways that it would be “easy to rig” the electronic ballots — and do so “without leaving a trace,” as his party insisted in a preelection report. That course of action, from a president long known as the “Trump of the tropics,” ensured that the controversy around the U.S. elections in 2020 would reverberate in the background of the Brazilian campaign season.

“There’s a little bit of that,” the international organization official said, referring to perceptions within Brazil and abroad that Bolsonaro imitated Trump’s team. “To be questioning this like now, it sounds to me to be copying things from Trump.”

Brazil has a reputation for operating “a thriving electronic voting system,” as international observers have described it — one implemented in part to mitigate the risk of fraud or bad-faith machinations after the votes are cast.

“In the 1994 national elections, for example, vote tabulation required about 170,000 people. Because of the scale of the task, vote counting could take weeks, and the post-election period was a time of great uncertainty and tension,” as the National Democratic Institute put it. “Most importantly, the lengthy tabulation period increased the opportunity for vote counters allied with candidates to manipulate the vote count.”

The acceleration of the vote counting has eliminated some of the uncertainty in Brazil that was a necessary condition of the disputes about the U.S. elections, in which protracted hand counts of paper ballots meant that the results of key races could not be known for days after the election.

“Obviously there are historical and good small-r republican reasons to have states [operate elections] … but there is tremendous benefit when it comes to the tremendous speed at which Brazil counts its votes,” Center for Strategic Institute and International Studies senior fellow Lauri Tahtinen said.

And the results showed a strong performance for Brazil’s conservatives. That makes for “a very similar dynamic in that sense to 2020,” as Haydar put it, when congressional Republicans in key battlegrounds such as Wisconsin received more votes against their Democratic opponents than Trump did against Biden.

“You are seeing internally among his allies within his party but also more broadly the coalition that he’s governed with … voices that have come out and have constrained his options already from the get-go,” the Heritage Foundation analyst said. “There are plenty of people sitting there thinking, ‘They did well.’”

One of Bolsonaro’s close allies, Tarcisio de Freitas, won the race to be governor of the state of Sao Paulo, the home of Brazil’s largest city.

“I don’t know if he’ll speak tonight or tomorrow. … He was sad. He expected a different result. But he will accept the results,” de Freitas told local media Monday. “The ballot boxes are sovereign.”

Such public statements from within Bolsonaro’s coalition might be bad for their defeated leader but good for Brazil’s system of governance.

CLICK HERE TO READ MORE FROM THE WASHINGTON EXAMINER

“It is a sign of a healthy democracy when the leaders of the institutions come out and say, ‘Let’s respect the results of the elections,’” the senior international organization official said.