–>

February 2, 2023

As I recently had to prepare a lecture series on the kings of Spain, I stumbled upon a striking parallel between the United States today and Spain 300 years ago.

‘); googletag.cmd.push(function () { googletag.display(‘div-gpt-ad-1609268089992-0’); }); }

In the fifty years between 1665 and 1715, the collapse of Spain’s monarchy led to the War of the Spanish Succession. In that war, Winston Churchill’s ancestor, the Duke of Marlborough, became an unforgettable historical figure.

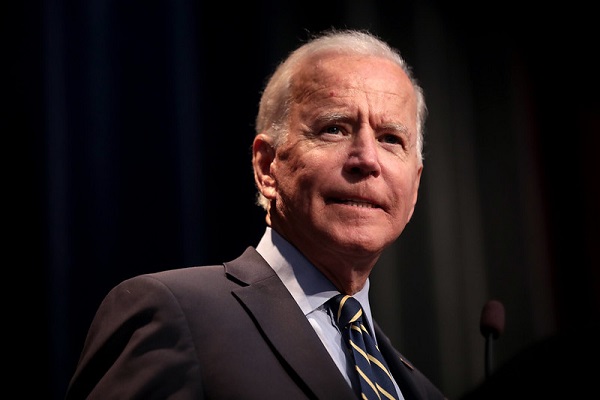

So much of what I found in studying this conflict reminds me of the United States today, especially because of the global anxiety caused by Joe Biden’s apparent fragility of mind and body. Perhaps some lessons can be learned here, or at least we can amuse ourselves by reflecting on Spain’s history and recalling the lines from Ecclesiastes: “There is nothing new under the sun.”

“El Rey Hechizado” or “The King Who Had a Hex on Him”

‘); googletag.cmd.push(function () { googletag.display(‘div-gpt-ad-1609270365559-0’); }); }

At the center of Spain’s dramatic decline was one of the most tragic monarchs in history: Carlos (or Charles) II of Spain. In 1665, his father, King Felipe IV, died. Carlos II was only four years old. His mother, Mariana of Austria, had to rule as regent. Because of the sexual escapades of Carlos’s father, he had an out-of-wedlock brother named Juan José de Austria; this person would militate against Carlos in attempts to gain power. But Carlos’s most lethal enemy was his own DNA.

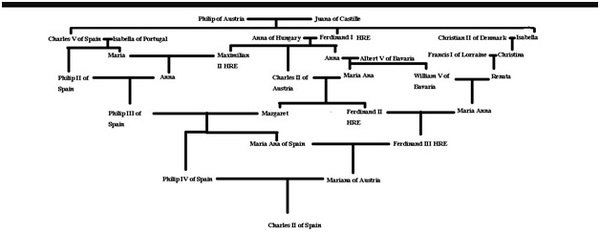

This was part of Carlos’s family tree:

Notice anything unusual?

Inbreeding and generous papal dispensations to marry cousins (as a reward for warring against the Protestants, Jews, and Muslims) had kept the vast territorial positions of this empire away from outsiders. But it denied these monarchs genetic diversity.

Since Carlos’s death in 1700, a consensus has formed among scholars that the generations of inbreeding caused his heartbreaking physical ailments. Many articles like this one in the “Vintage News” have focused on the autopsy performed by Spanish doctors after the king died:

[T]he physician who carried out the autopsy of the king’s body reportedly noted that the corpse “did not contain a single drop of blood; his heart was the size of a peppercorn; his lungs corroded; his intestines rotten and gangrenous; he had a single testicle, black as coal, and his head was full of water.”

‘); googletag.cmd.push(function () { googletag.display(‘div-gpt-ad-1609268078422-0’); }); } if (publir_show_ads) { document.write(“

Other scholars have perpetuated the centuries-old gossip about Carlos’s sexual identity, with some people claiming he may have been hermaphroditic. He could not father heirs with either of the two women he married.

The king’s infertility featured on a long list of deficiencies. According to the scholars who collaborated on this excellent miniseries, he did not walk until about age seven or speak until about age ten. Other history buffs point out that he never learned to read or write and “was totally dependent on those around him.” He could not eat most foods because his lower jaw protruded so far that he could not chew. Ministers manipulated him just as his mother and wives dominated him. Some records indicate that reforms under Carlos II were actually popular with the people, which explains why his reign ended with his death rather than by an overthrow. But this is due, ironically, to the fact that his weaknesses left a space for various reformers to make changes that appeased a populace traumatized by centuries of war, disease, and a turbulent economy.

The most lasting legacy of Carlos II was failed succession. Even if some changes in Spain alleviated popular discontent in the short run, his failure to produce an heir meant that the whole system on which Spain had depended broke down. He left conflicting wills before his death. In 1698, he had left a will naming a Hapsburg as his heir, but in 1700, one month before his death, he named a Bourbon. With no clear way to decide between the Austrian Hapsburgs and the French Bourbons, neither of whom was actually Spanish, the only way to settle the matter was war.

This was exactly what happened. The War of the Spanish Succession occasioned the legendary heroism of the Duke of Marlborough but rivals other wars for its absurdity and senselessness. According to author James Falkner:

After a period of military success, with Spanish armies within striking distance of the walls of Paris at one early point, Spain had lapsed from being a world power, despite its vast empire, and her ruling classes had sunk into commercial and intellectual indolence induced by the steady flow of treasure, unearned and therefore taken for granted, from the New World. (223)

Who Are We to Judge These People?

As I went down the rabbit hole studying the War of the Spanish Succession, I often had to remind myself that these events took place over 300 years ago. So many parallels to our own day emerge when you think of “had lapsed from being a world power, despite its vast empire … and her ruling classes had sunk into commercial and intellectual indolence induced by the steady flow of treasure, unearned and therefore taken for granted[.]”

Joe Biden stands befuddled and confused at a microphone, propped up by his peroxide blonde wife, muttering something unintelligible when asked why his son was making millions of dollars from companies whose directors were promised meetings with the vice president. Frail, fading, and often absent from the public eye, he is the aging version of Carlos II, a nerve-racking and incompetent figure who everyone knows isn’t running the country.

Who is running the country? In Spain, the Inquisition had functioned as the original Deep State for hundreds of years. By the dawn of the eighteenth century, people had become exhausted by pious religion. The prayerful enthusiasm for Isabel la Católica, mother of Carlos’s ancestress Juana la Loca, had long since passed. The Thirty Years’ War, which left Spain the worse for wear, had seemingly shocked the religious fanaticism out of people everywhere, including in Spain. There’s a haunting similarity to our own situation, as people no longer observe the taboos against “conspiracy theories” largely because conspiracies are too often real. One finds a weakening of the old pieties that compelled Americans to trust the FBI, CIA, and DOJ because communism and fascism were worse.

Instead of inbreeding and incest, we have massive gender confusion and an upper class so detached and self-enclosed that Ronna McDaniel, easily the most unlikable Republican in America, can get elected as RNC chair in a landslide after overseeing several cycles of electoral failure.

Like Spain, we are in massive debt and find our currency unable to stay dominant in the global economy of an encroaching century of change. Like Spain, we slowly grapple with the reality that it has been an enormously long time since we have actually won a serious war. Just as Spain had to face the humiliating reality that she could get the daylights beaten out of her by a flooded hamlet of Calvinist merchants like Holland, we can no longer deny that Taliban thugs were too much for the American empire to handle. “World power,” indeed.

Like the United States, once upon a time, Spain was the leader in human rights. The Burgos Laws of 1512 and the “New Laws” of 1542 had extended the crown’s legal protection to the native people of lands that Spain claimed to rule. For the sixteenth century, this was an incredibly important development, sometimes touted by Hispanophiles as the first time since Rome that an empire extended the legal rights of the homeland to acquired territories. But like Spain, the United States now finds itself in an impossible dilemma when it comes to ethnic diversity. The United States has invited the whole world to come to the U.S. to enjoy constitutional rights, in a sense accomplishing the inverse of what Spanish kings did.

Ethnic diversity is part blessing and part quagmire. In the time of Carlos II, the unity of an empire was crumbling as revolts from territories ranging from Italy to Catalonia to Flanders broke out. Meanwhile, Portugal, having been part of Spain only 100 years earlier, remained an irritant to the country’s west.

Back in the twenty-first century, a debt-laden America has announced “the largest aid package yet” sent to Ukraine, a land only dimly understood by people here. Antiwar Americans deserve some grace for finding themselves bewildered by how many overseas conflicts our country is entangled in.

Like Spain, our military is depleted. Like Spain, the sexual bedlam of our ruling elite is wreaking havoc on family structures in the country as a whole.

And yet the single most salient parallel is succession. Spaniards in 1700 had lived for hundreds of years with the assurance that monarchy worked, God favored it, and there would always be an heir. One can imagine the chaos they felt when Carlos II died childless, a doddering wretch even more shaky than Biden, and there was no heir. It is no coincidence that the Americans and the French rejected monarchy entirely in the century following. Spain’s catastrophe in 1700 had delivered an unforgettable lesson. Whatever arguments people might propose in favor of monarchy, it simply didn’t work.

And now we hear more about the January 6 Committee. There is nothing new under the sun.

For hundreds of years, like Spaniards, we Americans have lived with the assurances that our system was the best one. We never doubted that periodic elections would work, and there would always be a way to transfer power from one leader to another legitimate leader. And yet, like the people shocked that a king could die without a prince to survive him, we are slowly facing the reality that elections might not work anymore. There are too many reasons to cheat and too few ways to stop cheating. Is it possible — dare I even say it? — that the Constitution just won’t work in a country this big, with this many loopholes, and this many people who don’t believe election returns anymore?

All the grand ideals of liberal democracy depend on counting 160,000,000 ballots without cheating. It turns out that’s just as risky a presumption as assuming there will always be an heir apparent.

Perhaps 2020 was our version of Spain’s 1700. By December 2020, there was no heir. Biden’s our leader but not our president, for a whole host of reasons. He’s obviously too feeble to be running the country. Nobody can claim with 100% certainty that he won the election. If he isn’t in charge, someone is, and it isn’t anyone we elected, nor anyone we trust, so there is no president, because we don’t have a Constitution.

Where do we go from here? Studying the last days of Carlos II scares me because that’s a question that Spanish history cannot answer. A war that lasted until 1714 decided who would be the next Spanish king (the Bourbons won). But I don’t think we can even decide America’s future with a war. The vast holdings of America’s empire are indeed up for grabs, just as Spain’s were, but it seems more likely that a wild propaganda maelstrom and corporate raiding will decide who gets the riches and who is stuck with famine, sickness, and penury. After monarchy, there was an Enlightenment and liberal democracy to take the lead. After liberal democracy, what is there?

Your guess is as good as mine.

WORKS CITED

James Falkner, War of the Spanish Succession 1701–1714, Pen & Sword Books, South Yorkshire: 2015. Kindle Edition.

Image: Gage Skidmore via Flickr, CC BY-SA 2.0.

<!– if(page_width_onload <= 479) { document.write("

“); googletag.cmd.push(function() { googletag.display(‘div-gpt-ad-1345489840937-4’); }); } –> If you experience technical problems, please write to [email protected]

FOLLOW US ON

<!–

–>

<!– _qoptions={ qacct:”p-9bKF-NgTuSFM6″ }; ![]() –> <!—-> <!– var addthis_share = { email_template: “new_template” } –>

–> <!—-> <!– var addthis_share = { email_template: “new_template” } –>