We Can Defend What We Choose to Defend

In response to attacks and tragedy from terrorists and from psychos, we’ve “hardened” many potential targets, including the White House, the Capitol, federal office buildings, and airports. The French have even made the Mona Lisa a hard target. All this is fitting and proper. If something valuable is “soft” or vulnerable, then it needs to be defended.

So now, in the wake of the mass murder in Uvalde, TX, on May 24, we must do what we should have done a long time ago: harden the schools. America’s children are worth it.

Many proposals have been put forward. Here, for example, are ideas from A.W.R. Hawkins of Breitbart News, from Sen. Lindsey Graham (R-SC), and from House Republicans. Also, here’s a 2018 report from the U.S. Secret Service. The various proposals have a common thread: Effective hardening of a target involves the interplay of identifying, deterring, and neutralizing the attacker.

Even a Washington Post columnist, Kathleen Parker—a onetime conservative who has moved fashionably, if not completely, to the left–agrees with the idea of active, armed defense:

The very least we can do is make sure every school in this country is safe from predators, no matter the cost. And, yes, train and arm the teachers who are willing. No more fooling around.

Indeed, a new poll out shows that a majority of Americans favor arming teachers as an option.

Needless to say, it would be better if the police were handling school security. And yet the apparent failure of the Uvalde authorities is a sobering reminder that absent strong leadership, a deterioration of professionalism can happen to any organization. As they say in the U.S. Army, a low standard becomes the new standard.

So the coming investigation of the Uvalde tragedy will serve as an opportunity for the nation to learn about how to harden a target. For instance, beyond the mistakes made during those calamitous 78 minutes on May 24, investigators should ask: Has the vilification of the police these past few years had an effect on police morale? On cops’ willingness to take risks, knowing that they could be sued or fired?

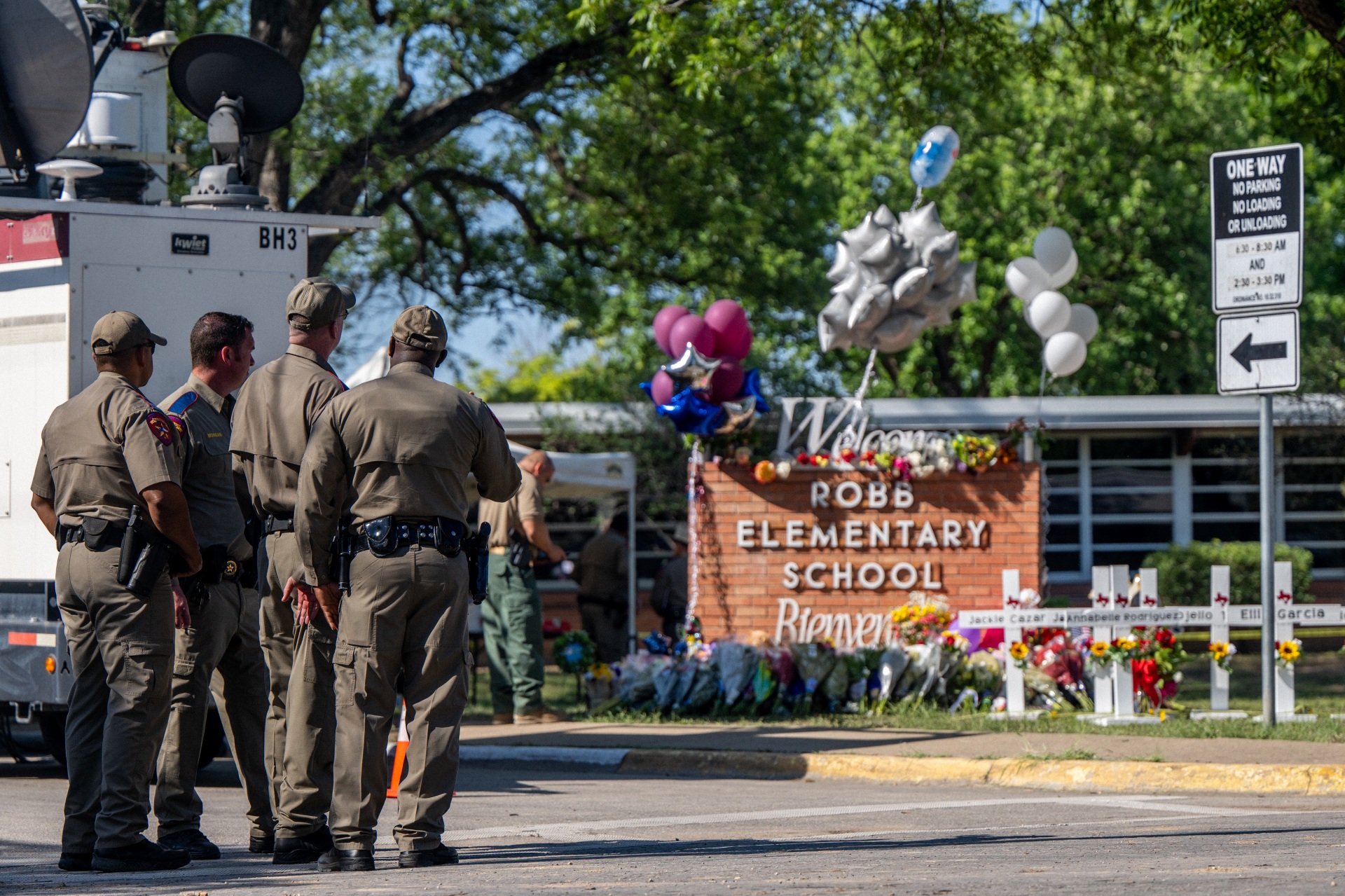

Law enforcement officers stand looking at a memorial following a mass shooting at Robb Elementary School on May 26, 2022 in Uvalde, Texas. (Brandon Bell/Getty Images)

Have procedures for dealing with troublesome students and others made it easier for them to become menaces to society? We can observe that the American Civil Liberties Union and other liberal-left leniency groups have often intervened in a school’s “discipline matrix”—and such outside intervention was a major factor in the 2018 massacre at Marjory Stoneman Douglas High School in Parkland, Florida.

Authorities should also ponder what technological solutions might be possible. A May 27 Breitbart News report outlined some of the challenges the cops faced in Ulvalde:

Officers could not see into the classrooms to determine where the shooter was and what tactical advantages he might have. The shooter had the tactical advantage the entire time.

We can pick through these details and begin to see what combination of cameras, drones (including micro-drones that could fly through windows or vents), and robots (the kind that could potentially batter down a door or a wall) might prove to be helpful for the next emergency.

Because the one thing we know is that the problem can be solved. For instance, Israel suffered a surge in suicide bombing attacks during the so-called “second intifada” at the beginning of this century. In 2000, the Jewish state suffered just four suicide bombings; the following year, that number jumped to 35, and year after that, the number of attacks spiked to 53. Thousands of Israelis were killed or injured, and the remainder of the population was terrorized.

And yet Israeli homeland security officials developed better strategies—everything from detection-tech to human profiling to counter-intelligence—and beat back the problem. By the end of the decade of the aughts, the number of “successful” suicide bombings had fallen to zero.

Interestingly, many Democrats have come out against hardening school targets. That was the message from Sen. Charles Schumer (D-NY) on May 26: “Hardening schools would’ve done nothing to prevent this shooting . . . More guns won’t protect our children.” That’s a strange thing to say, since it was literally a good guy with a gun that killed the bad guy with a gun. (That authorities grossly mishandled the situation doesn’t change the fact that the good guy–apparently ignoring orders to stand down–used his gun to kill the killer.) That same day, May 26, Schumer used his power as senate majority leader to block a Republican school-safety proposal.

Monique Rodriguez (R), mother of Audrey and Aubrey Ramirez, lay flowers at a makeshift memorial outside the Uvalde County Courthouse in Uvalde, Texas on May 27, 2022. (CHANDAN KHANNA/AFP via Getty Images)

Why this opposition to hardening the targets? One reason is that many on the left just simply don’t believe in policing. Perhaps, too, progressives fear that a hardened-target plan would work, thereby draining away energy from their favored solution, gun control—or even Constitution-trampling gun confiscation.

This progressive stance makes for some strange arguments. Here, for example, is some tweet-wisdom from Chasten Buttigieg—husband of transportation secretary Pete Buttigieg—reacting operatically to suggestions about hardening entrances to schools:

A door is good at keeping the kids in and rain out. It doesn’t stand a chance against a weapon designed to obliterate organs and render tiny bodies unrecognizable in the blink of an eye. If you’re focusing on doors right now, you’ve already given up. You have failed our kids.

A door is good at keeping the kids in and rain out. It doesn’t stand a chance against a weapon designed to obliterate organs and render tiny bodies unrecognizable in the blink of an eye. If you’re focusing on doors right now, you’ve already given up. You have failed our kids.

— Chasten Buttigieg (@Chasten) May 26, 2022

Buttigieg’s dim assessment of doors would be news, of course, to anyone who ever built or made use of a lock or gate. (As an aside, over the last six years, this author has written much about the value of “passive defenses,” here, here, here, and here.)

Buttigieg continued, warning against the dreaded “they”:

Let me be clear: this is precisely what they want. They want to debate the merits of doors, windows, locks, cameras, badges, and armed teachers because they’d hate to be faced with yet another policy issue they are against the majority of Americans on.

In point of fact, it’s not obvious what an actual majority of Americans want. Yes, polls, but as The New York Times reluctantly conceded on June 3, survey polls don’t predict the judgments Americans make at actual voting polls.

Moreover, someone might wish to tell Mr. Buttigieg that the other Mr. Buttigieg, the one in Joe Biden’s cabinet, is exactly protected by “doors, windows, locks, cameras, badges,” as well as, of course, armed guards.

Speaking of arms, Americans not entitled to 24/7 security are arming up.

The Philadelphia Inquirer reports that in Pennsylvania:

gun sales surged in 2020 by 49% over the prior year, with a total of 1,141,413 firearms reported as either lawfully purchased or privately transferred, according to data from the Pennsylvania State Police. Licensed firearm dealers accounted for the vast majority of those transactions.

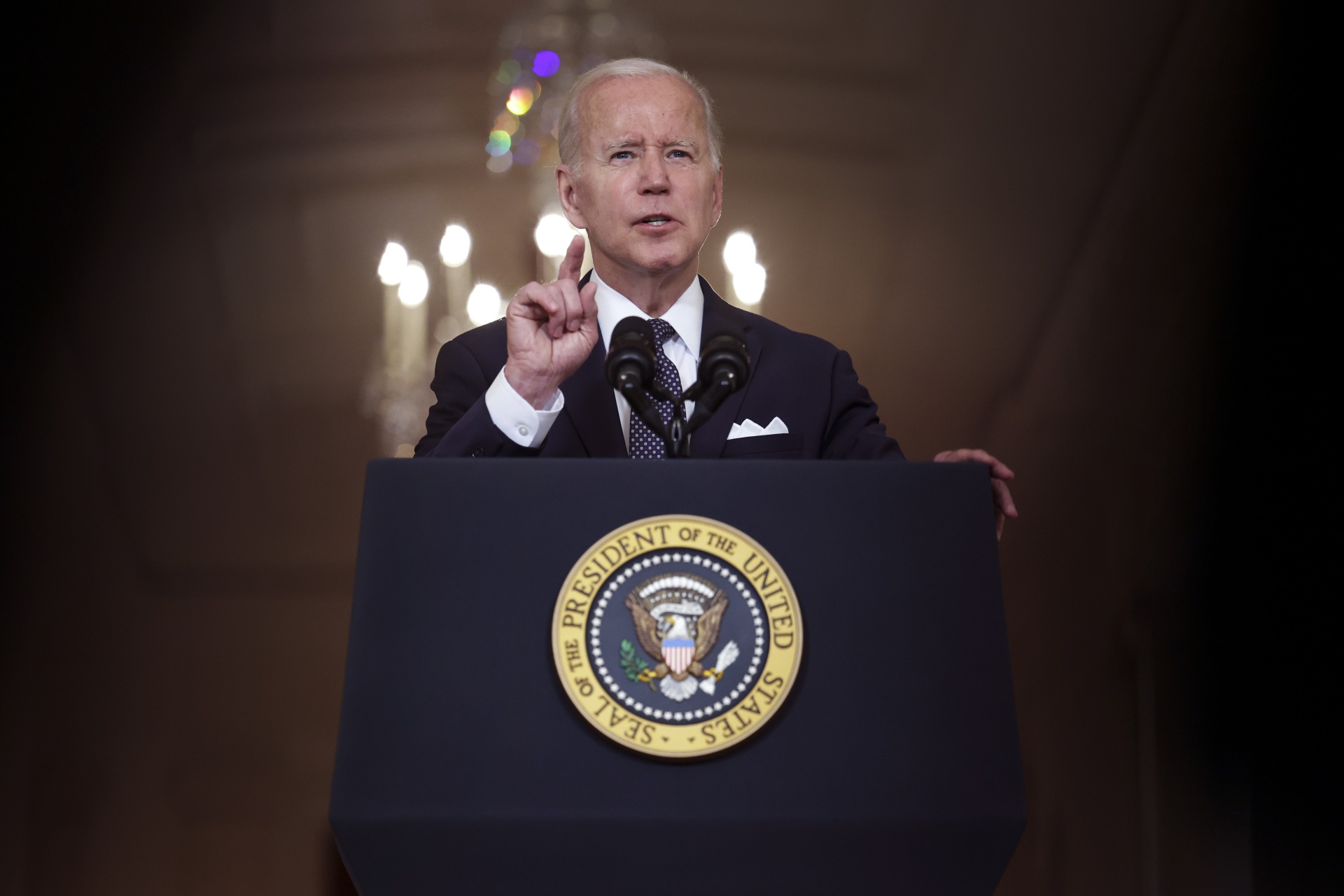

That’s 1.1 million guns, in a single year in a single state. Gun controllers—including President Biden, who delivered a prime-time speech on June 2—can talk about gun control all they want (notably, Biden did not mention hardening) and might score a success here or there, but the practical reality is that America’s gun culture is here to stay.

After all, few events these past few years have made Americans think that they don’t need to be able to protect themselves. Oops! Did I say “few events”? I meant, no events! In this crazy world, where the cops sometimes mill around even as children are getting shot, the last line of defense for you and yours is…yourself.

President Joe Biden delivers remarks on the recent mass shootings from the White House on June 2, 2022 in Washington, DC. (Kevin Dietsch/Getty Images)

Not Gun Control, Evil Control

Off the top of your head, would you say it’s possible that shoot ‘em up videogames are a contributing factor in the deranged thinking of young male school shooters? Yeah, that’s what I think, too.

Studies indicate that some 90 percent of American kids play video games—and for boys, the percentage could be as high as 99. And when we say “play,” we mean hours on end. Most of these games, of course, are first-person shooters, which means that the average player “kills” thousands, maybe even millions, of pixelated targets.

And let’s not forget another content-provider for screens; as Richard Rushfield writes:

Where is the biggest, highest production values celebration of gun culture on Earth happening? It’s not at an NRA rally; its right on your screen, put there by your good progressive friends in Hollywood.

For an impressionable crazy few, is such on-screen shooting a kind of target practice for real life? We can answer that question with another question: What is there, appearing on a screen, that someone, somewhere, has not wished to imitate?

Now of course, the chances of banning violent videogames are about the same as banning guns. If so, then we just have to get used to the fact that a tiny minority of videogame players, just as gun possessors, are going to be a danger. And maybe that’s one challenge of living in a free society. Yet at the same time, we can agree with Joe Rogan: ”This country has a mental health problem disguised as a gun problem.”

So if we wish to improve mental health, we might take some lessons from the experts. Fortunately, such expertise goes way back. Two of the greatest political thinkers in history, Aristotle and Confucius, agreed on one thing: statecraft is soulcraft. That is, if you want to have a good society, you have to make arrangements for a good population, and that means moral and ethical instruction, especially for the young. As a contemporary political observer, Thomas Sowell, tells us, “Each new generation born is in effect an invasion of civilization by little barbarians, who must be civilized before it is too late.”

Across history, civilizations have adopted various strategies for teaching people to be good. In old churches and cathedrals, for instance, scenes of sinners burning in hell were a common feature of the surroundings. Such visuals, we can say, were the video screens of five hundred or a thousand years ago.

The Massachusetts Puritan John Winthrop emphasized another aspect of generating goodness: strong community. As he said in his famed “City on a Hill” sermon of 1630:

Wee must delight in eache other; make other’s conditions our oune . . . as members of the same body. Soe shall wee keepe the unitie of the spirit in the bond of peace.

The song “America the Beautiful,” written in 1895, emphasizes another key point of good behavior: personal responsibility. A key lyric: “confirm thy soul in self control.”

So now we can look around today and ask: To get the message of personal virtue across, are we still hitting on all these societal cylinders? Answer: obviously not.

Reacting to an earlier school shooting, former Los Angeles police officer J. Warner Wallace identified four driving causes: “an increase in social media use”; “an increased dependency on prescription medicine”; “an increase in single parent households”; and “a decrease in traditional Christian values,” including, we can add, the belief that bad people go to hell where they are tormented forever. It’s too bad that the idea of hell, just as the notion of evil, has been mostly banished by our secular culture.

So now maybe we should ask: Will the metaverse, as championed by Mark Zuckerberg and other Tech Lords, feature any kind of worthwhile moral instruction? Or will it be all fantasy feel-good with, maybe, woke relativism? Or will it be more of the deadly nihilism we see in many video games?

In light of the current crisis, it seems necessary to start getting into these soulcraft mechanisms, starting with the media. One who makes this point well is Elliot Ackerman, who served eight years in the Marines, including multiple tours in Iraqi and Afghan combat zones. He began a recent article by citing academic studies showing that over-the-top media coverage does, indeed, inspire copycats. And after further considering the power of media narratives to excite the worst among us, Ackerman concludes:

A sickness is sweeping our land; one of its symptoms is these shootings. A certain subset of young men is trying to bring meaning to their lives through gun violence. Stories are where people have always gone to find meaning. We need to tell a different story; the current one is killing us.

In the meantime, some are, in fact, telling better stories—stories of kindness to one another, and of mutual support. To name one, there’s the Foundation for a Better Life, airing inspirational TV spots urging, “pass it on.” That is, pass on the goodness.

To name a second, we might consider the welcoming message from the little town of Bluefield, WV:

Moving to Bluefield means becoming part of a unique community of 10,500 friends and neighbors in which everybody takes care of each other and makes his contribution to a safe and lovely haven to settle down.

We can immediately observe that Bluefield is hardly alone in its communitarian pitch; thousands of towns and locales have the same appeal. To be sure, not everyone can live in a friendly little town, but everyone, everywhere, can be friendlier, seeking to live by the golden rule.

And perhaps it’s even possible that the Internet could help, for a change.

For instance, what if everyone who wanted to be good took a pledge to be good, and recorded it on the Internet? On a website? What if, maybe, a golden thread were to connect pledge-takers, virtually?

There’d be nothing mandatory about this, it could just be a voluntary pledge—and a badge of honor. Needless to say, some would laugh at any display of piety. Yet still, as in the 1951 Norman Rockwell painting, “Saying Grace,” a quiet display of devotion can make an impression, even on the graceless—and it can receive a high valuation.

It’s worth recalling that faith groups have been willing to step forward and identify themselves as believers and adherents, perhaps through an article of clothing, perhaps just by holding themselves to a higher standard.

Indeed, in the past, many communities have even called themselves “saints,” not because they thought they were perfect, but because they were mindful of the perfect—and that, in turn, helped regulate their earthly behavior. To this day, the official and proper name for the Mormons is the Church of Jesus Christ of Latter-Day Saints (LDS). And Utah, so much shaped by LDS, has benefited from a private, voluntary, non-governmental social and cultural structure that emphasizes and reinforces positive values. No wonder Utah is nice place to live.

We can, and should, harden all the soft targets in our society. But we should keep in mind: The ultimate hard target is the human soul. If we can make that sturdy, resilient, honorable, and gentle, we will be fine. But if we can’t, then all is lost.