As public interest skyrockets in artificial intelligence services such as OpenAI’s ChatGPT and Google’s Bard, Washington has developed a serious case of FOMO — the fear of missing out.

But as regulatory proposals begin to take shape, a familiar problem is presenting itself: Do politicians understand the technology well enough to meddle without also risking its potential benefits?

BIDEN ADMINISTRATION TAKES STEP TOWARD REGULATING AI WITH REQUEST FOR INPUT

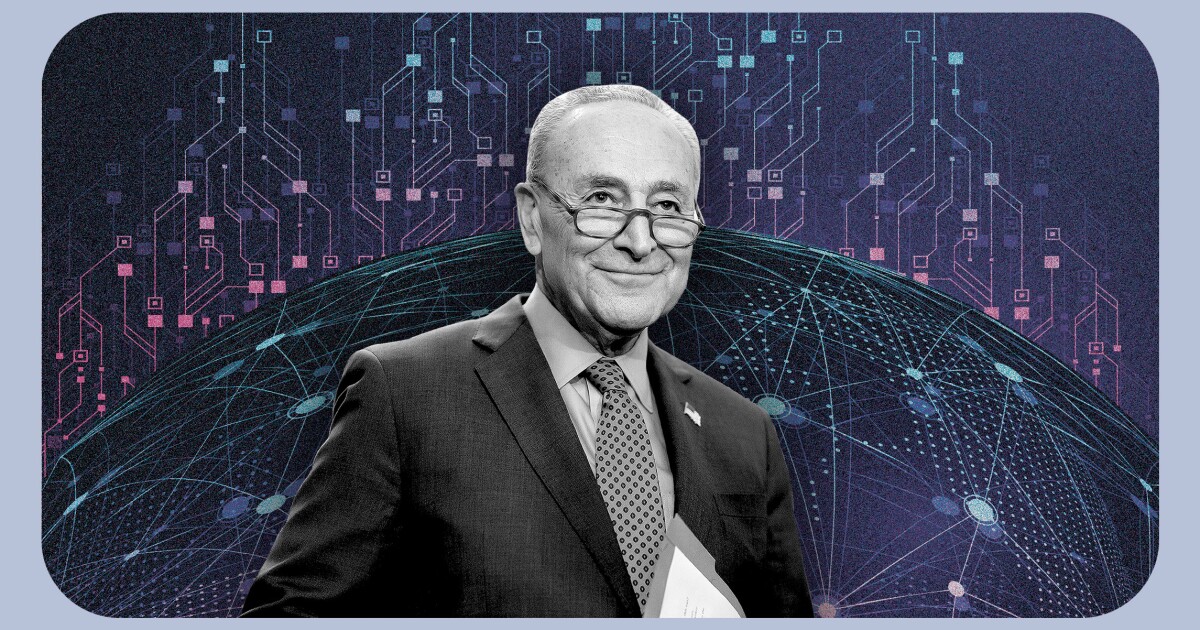

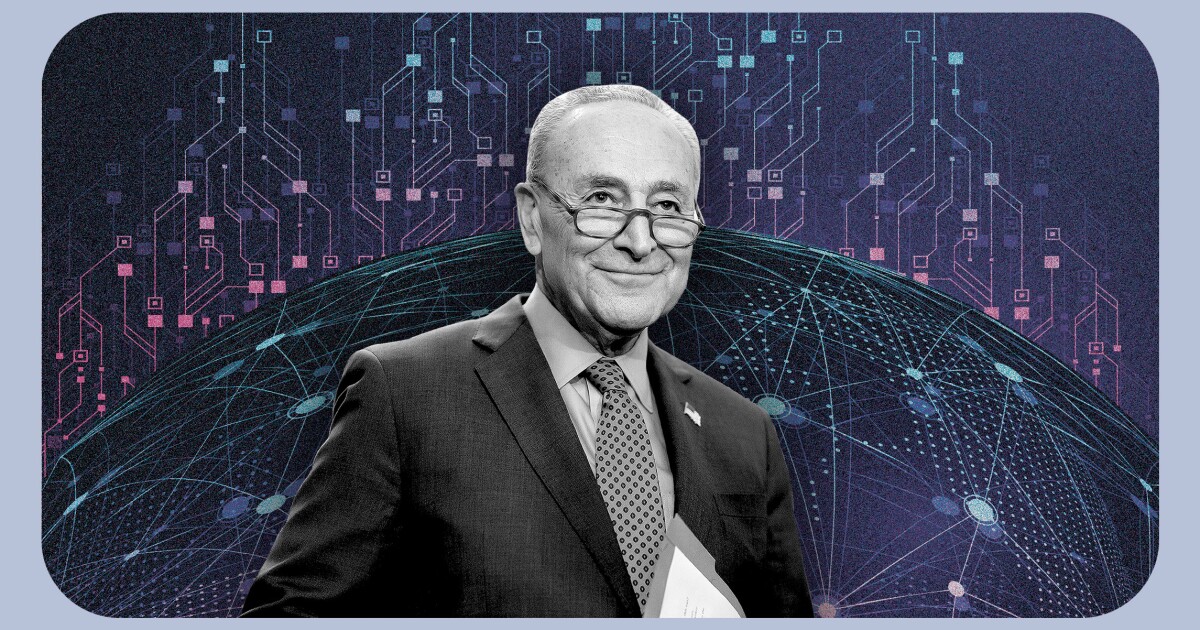

Senate Majority Leader Chuck Schumer (D-NY) is reportedly working on a legislative proposal to set federal standards for allowing American organizations to operate what’s known as generative AI. This type of artificial intelligence can generate new data by recognizing patterns in existing data — AI that learns by doing, like the popular new chatbots.

According to Axios, the Schumer plan would include four initial requirements or “guardrails” for the technology: identifying who trained the AI algorithm, the intended audience, its data sources, and response mechanisms, as well as strong, transparent ethical boundaries.

These are meant to form a broad framework for the development of future AI. And like all regulatory proposals, they are aimed at mitigating anticipated risks while also preserving the potential benefits of innovations.

But members of the Senate don’t have a good track record for being tech-savvy. In 2006, the late Alaska GOP Sen. Ted Stevens (R-AK) described the internet as “a series of tubes.” Though not wholly inaccurate, he was subjected to popular ridicule for the comment. In a 2018 hearing, the late Sen. Orrin Hatch (R-UT) asked Mark Zuckerberg how Facebook made its money. The CEO of the second-largest advertising platform on the internet replied, “Senator, we run ads.”

A lack of working knowledge may have contributed to the failure of antitrust laws aimed at Big Tech during the last legislative session of Congress. Now, the same lack of tech literacy by legislators may hinder efforts to regulate AI.

“What’s interesting is that nearly all of the ‘four guardrails’ that are steering the conversation are already being implemented by the company that is leading this charge, OpenAI,” Will Rinehart, a senior fellow at the Center for Growth and Opportunity at Utah State University, told the Washington Examiner. “And the other major company in this race, Anthropic, is competing with even more safety and protections built in.”

If the Senate is behind the regulatory curve, the House may be faring a bit better. Members have voiced concerns about AI in House floor speeches, but they’ve introduced little legislation to address those concerns.

A resolution “expressing the sense of the House of Representatives that the United States should negotiate strong, inclusive, and forward-looking rules on digital trade and the digital economy” and a bill ensuring the military can employ AI reflect an acknowledgment that this technology is a genie that can’t be put back in its bottle.

Perhaps that’s because the House boasts a few tech-focused members. Rep. Ted Lieu (D-CA) introduced the first-ever piece of federal legislation written by AI. The resolution states that AI “has the potential to greatly improve the lives of Americans and people around the world, by increasing productivity, improving health care, and helping to solve some of the world’s most pressing problems.”

Rep. Jay Obernolte (R-CA) is a computer engineer and video game developer who graduated from the California Institute of Technology. Obernolte also is the only member of Congress with a master’s degree in AI, from UCLA. He has been outspoken about a lack of tech knowledge among his fellow representatives.

“You’d be surprised how much time I spend explaining to my colleagues that the chief dangers of AI will not come from evil robots with red lasers coming out of their eyes,” Obernolte recently told reporters.

But nascent regulatory efforts in Washington aren’t confined to Capitol Hill.

This month, the Commerce Department’s National Telecommunications and Information Administration asked for public comment on shaping rules for AI development. The agency could go on to mandate audits as part of procuring government contracts to guard against biases in algorithms AI technologies use. The public will have 60 days to weigh in before administrators issue a report with specific policy proposals.

Last fall, the White House struck a more pessimistic tone when it issued its own best-practices recommendations for what should be built into AI technologies. A senior official in the Biden administration warned on a call with reporters that these AI “technologies are causing real harms in the lives of Americans” during the rollout of the White House’s Blueprint for an AI Bill of Rights.

The principles are not binding law, but the administration hopes to put pressure on technologists to build in certain protections. Specifically, the suggestions include that AI should be safe, be free from algorithmic discrimination, keep users in control of their data, be transparent, and allow users to opt out of the AI and opt in for a human interaction instead. The European Union issued AI guidelines in 2019, and the Vatican weighed in with its AI concerns in 2020.

CLICK HERE TO READ MORE FROM THE WASHINGTON EXAMINER

But the long struggle for a comprehensive way to regulate the rapidly changing field of artificial intelligence may prove too complicated a race for politicians to win.

“To me, the effort to regulate AI seems misplaced,” Rinehart said. “Congress has for years failed to pass privacy legislation, which would do a lot to accomplish the goals Sen. Schumer has laid out. What’s needed isn’t another grand vision.”