(function(d, s, id) { var js, fjs = d.getElementsByTagName(s)[0]; if (d.getElementById(id)) return; js = d.createElement(s); js.id = id; js.src = “https://connect.facebook.net/en_US/sdk.js#xfbml=1&version=v3.0”; fjs.parentNode.insertBefore(js, fjs); }(document, ‘script’, ‘facebook-jssdk’)); –>

–>

August 3, 2023

Just two days apart, I watched the movie Oppenheimer and read the most recent indictment of Donald Trump by the “United States of America.” In watching the film, even before reading the indictment, I sensed parallels in the hounding of both Oppenheimer and Trump.

‘); googletag.cmd.push(function () { googletag.display(‘div-gpt-ad-1609268089992-0’); }); document.write(”); googletag.cmd.push(function() { googletag.pubads().addEventListener(‘slotRenderEnded’, function(event) { if (event.slot.getSlotElementId() == “div-hre-Americanthinker—New-3028”) { googletag.display(“div-hre-Americanthinker—New-3028”); } }); }); }

The indictment suggests that the two men were persecuted for the same offense — free speech. “The defendant had a right, like every American, to speak publicly about the election,” insists prosecutor Jack Smith. Similarly, no one denied Oppenheimer his right to lobby for one-world government and international cooperation.

The problem in each case is that the speaker had too big a platform and too loud a voice. That said, the motives for shutting down Oppenheimer were far more substantial than they are for Trump. The penalties imposed on Oppenheimer, however, were far less. He lost his security clearance. That’s pretty much it.

Great American Movies (GAM) come along rarely, more rarely, it seems, with each passing year. Oppenheimer ends a 10-year drought since Steven Spielberg’s Lincoln. To qualify as a GAM, in my humble estimation, a movie should tell a big story, tell it exceedingly well, and tell it fairly. Oppenheimer, I believe, does all the above.

‘); googletag.cmd.push(function () { googletag.display(‘div-gpt-ad-1609270365559-0’); }); document.write(”); googletag.cmd.push(function() { googletag.pubads().addEventListener(‘slotRenderEnded’, function(event) { if (event.slot.getSlotElementId() == “div-hre-Americanthinker—New-3035”) { googletag.display(“div-hre-Americanthinker—New-3035”); } }); }); }

In a story this complex and nuanced — Robert Oppenheimer (Cillian Murphy) is no Abe Lincoln — there a thousand ways to go wrong. British-American writer/director Christopher Nolan avoids at least 990 of them. The one major ideological snare that Nolan sidesteps is the whitewashing of America’s Reds. The people hovering in Oppenheimer’s orbit — his wife, his brother, his mistress — are not merely persecuted liberals, as Hollywood usually depicts its commies, but card-carrying members of Josef Stalin’s Communist Party.

At least a few of the communists are seen plotting to betray the United States by giving America’s atomic secrets to the Soviets. One of them, the German-born Klaus Fuchs (Christopher Denham) who worked under Oppenheimer at Los Alamos, was eventually arrested and imprisoned for espionage.

Although Fuchs’s arrest is an important plot point, Nolan gives this subplot no more than two minutes of screen time. If a viewer misses the point, the fault is not Nolan’s, but the state of public education. To appreciate the movie, it would help viewers to acquaint themselves beforehand with the cast and characters.

Although Fuchs’s arrest is an important plot point, Nolan gives this subplot no more than two minutes of screen time. If a viewer misses the point, the fault is not Nolan’s, but the state of public education. To appreciate the movie, it would help viewers to acquaint themselves beforehand with the cast and characters.

A more developed subplot involves Oppenheimer’s close friend Haakon Chevalier (Jefferson Hall), a Berkeley colleague Oppenheimer knows to be a communist. When Chevalier tries to enlist Oppenheimer in a scheme to share secrets with the Soviets, Oppenheimer fails to report the overture to his superiors. Then, when found out, he lies to protect Chevalier. Knowing this, viewers understand the reasons why authorities might have wanted to rescind Oppenheimer’s security clearance after the war.

Nolan also avoids the red herring that Oppenheimer, a secularized Jew, was a victim of anti-Semitism. As the movie makes clear, German anti-Semitism proved to be America’s greatest asset in developing the atomic bomb. Several of the most prominently scientists involved in the Manhattan Project, directly or otherwise, were Jewish refugees. Those seen in the film include Einstein, Leo Szilard, and, most critical to the plot, Edward Teller (Benny Safdie).

One major plot line pits the Hungarian-born Teller against the American Oppenheimer in shaping America’s nuclear future. Nolan lets Safdie play Teller as something of a heavy with no larger goal than to build a “super,” a hydrogen bomb capable of blowing up the word. The unknowing audience member instinctively sympathizes with the peace-loving Oppenheimer who restrains Teller’s ambitions.

‘); googletag.cmd.push(function () { googletag.display(‘div-gpt-ad-1609268078422-0’); }); document.write(”); googletag.cmd.push(function() { googletag.pubads().addEventListener(‘slotRenderEnded’, function(event) { if (event.slot.getSlotElementId() == “div-hre-Americanthinker—New-3027”) { googletag.display(“div-hre-Americanthinker—New-3027”); } }); }); } if (publir_show_ads) { document.write(“

Savvy viewers, however, know that Teller was right. Only the threat of nuclear annihilation kept the Soviets at bay for the 40 years they had the power to attack western Europe or the United States. A cradle globalist, Oppenheimer wanted to share our secrets with the world. In the four years after Hiroshima, before they developed their own bomb, the Soviets had the same goal in mind.

In the movie, Nolan lets Teller make his case and lets others reinforce it. There is no evidence that Oppenheimer, in preaching the gospel of international cooperation, was working for the Soviets. But from the perspective of the nuclear realists like Truman and Teller, it almost didn’t matter.

Politically, of course, Trump and Oppenheimer are worlds apart. Trump is a nationalist and Oppenheimer a textbook internationalist. On a personal level, however, they have much in common. Both are New Yorkers born to money. Each has more than a touch of hubris. Neither was particularly faithful to his spouses, and each, ironically, was accused of colluding with Russians.

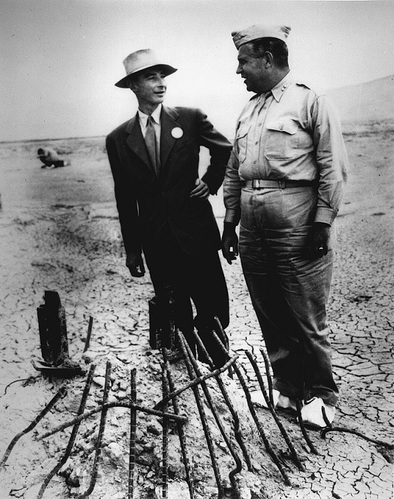

Above all, both were builders. Few others could have pulled Los Alamos together the way Oppenheimer did. Knowing this, Gen. Leslie Groves — played with bravura by Matt Damon — took a chance on Oppenheimer despite his communist sympathies and relationships.

Successful builders do not suffer fools gladly. Trump has made any number of enemies out of one-time allies, and Oppenheimer did the same. His public humiliation of his patron, businessman Lewis Strauss (Robert Downey Jr.), turned the vengeful Strauss against him and led eventually to the loss of his security clearance.

Despite his Marxist sympathies, Oppenheimer could not conceal his class bias against Strauss, an insecure Jewish “shoe salesman.” By contrast, the anti-Marxist Trump has few, if any, airs. Despite his wealth, he has done an unprecedented job of rallying the working classes to his cause.

As Strauss tells Oppenheimer in the film, he did him a favor by making him a martyr. He was right. The world’s liberal elite admire no one more than a victim of the bogeyman they call “McCarthyism.” They have forgiven Oppenheimer for building the atom bomb and have even chosen to forget that he “named names,” the one sin Hollywood still presumes to recognize.

Nolan blasts through those liberal pieties. He shows Oppenheimer for the brilliant but self-destructive man he was. Having conservative actor James Woods serve as the film’s executive producer had to help keep the train on the track.

Hollywood, of course, will inevitably make movies about Trump. The odds that the films will be as fair as Oppenheimer are no better than the odds that the Japanese would have soon surrendered had we not shared with them Oppenheimer’s “gadget.”

Jack Cashill’s new book, Untenable: The True Story of White Ethnic Flight from America’s Cities, is now available in all formats.

Image: Dept. of Energy

<!–

–>

<!– if(page_width_onload <= 479) { document.write("

“); googletag.cmd.push(function() { googletag.display(‘div-gpt-ad-1345489840937-4’); }); } –> If you experience technical problems, please write to [email protected]

FOLLOW US ON

<!–

–>

<!– _qoptions={ qacct:”p-9bKF-NgTuSFM6″ }; ![]() –> <!—-> <!– var addthis_share = { email_template: “new_template” } –>

–> <!—-> <!– var addthis_share = { email_template: “new_template” } –>