As migrants from Central America surge north in hopes of reaching the porous US border, businessmen and elected officials have turned the journey into a well-oiled, and profitable, machine - making "tens of millions" of dollars per year (or more, see below).

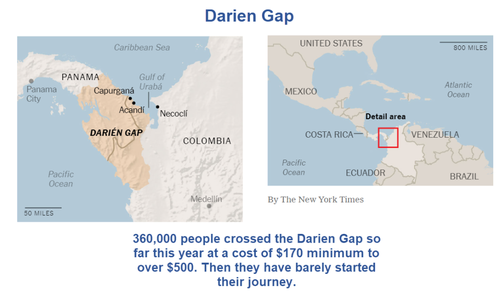

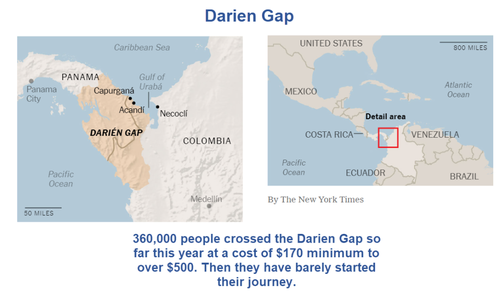

The Darién Gap, once a formidable natural barrier between North and South America, has essentially become a marketplace. Remote and beautiful, a constellation of small towns leading to the gap has been become a hub for mass migration, according to the NY Times.

The towns are riddled with poverty, and are housing a population that has long been victims of the country's internal conflicts. Their sewage, water, and electricity systems, already frail, were overwhelmed when thousands of Haitians began to show up in 2021, fleeing the chaos that spiraled after their President's assassination.

The Darién Gap has quickly morphed into one the Western Hemisphere’s most pressing political and humanitarian crises. A trickle only a few years ago has become a flood: More than 360,000 people have already crossed the jungle in 2023, according to the Panamanian government, surpassing last year’s almost unthinkable record of nearly 250,000.

In response, the United States, Colombia and Panama signed an agreement in April to “end the illicit movement of people” through the Darién Gap, a practice that “leads to death and exploitation of vulnerable people for significant profit.” -NY Times

Opportunists seize the day

"This is a beautiful economy," said Fredy Marín, a former town councilman from the municipality of Necoclí, who operates a boat company that ferries migrants on their way to the US. Marín says he moves thousands of people per month for $40 per head.

Marín is now running for mayor of Necoclí, where he's vowed to preserve the thriving migration industry, which has led to locals selling essentials like tents, snake repellent, and even toddler-sized rubber boots to migrants.

Elected community board members, like Darwin García in Acandí, Colombia, even describe the explosion of migrants as the “best thing” for their struggling communities.

"We have organized everything: the boatmen, the guides, the bag carriers," said García, who added that the flood of "migrants the best thing that could have happened" to their impoverished town. García's younger brother, Luis Fernando Martínez, is running for mayor of Acandí on this platform of sustaining the so-called 'migration economy.'

The migrants can even hire a sort of "security" service from groups like the New Light Darién Foundation, which offers a guided journey for migrants navigating the gap.

The foundation has hired more than 2,000 local guides and backpack carriers, organized in teams with numbered T-shirts of varying colors — lime green, butter yellow, sky blue — like members of an amateur soccer league.

Migrants pay for tiers of what the foundation calls “services,” including the basic $170 guide and security package to the border. Then a migration “adviser” wraps two bracelets around their wrists as proof of payment. -NY Times

The service is "Like a ticket to Disney," said Renny Montilla, 25, a construction worker from Venezuela.

Whose fault is this?

On the surface, Colombian and U.S. governments have expressed commitments to curb this illicit flow. However, actions on the ground tell a different story. Colombia’s President Gustavo Petro says the United States caused this migration crisis while showing no interest in curbing it, and says that the roots of this migration were "the product of poorly taken measures against Latin American peoples."

The New York Times has spent months here in the Darién Gap and surrounding towns, and the national government has, at best, a marginal presence.

When the national authorities can be seen at all, they are often waving migrants through, or in the case of the national police, fist-bumping the men selling expensive travel packages through the jungle.

The top police official in the region, Col. William Zubieta, said it wasn’t his job to halt the flow. Instead, he argued, the nation’s migration authorities should be exerting control.

“Unfortunately, they do not have it,” he said.

...

He [Petro] said he had no intention of sending “horses and whips” to the border to solve a problem that wasn’t of his country’s making.

In the absence of the Colombian government, local leaders have decided to handle migration themselves. -NY Times

Further complicating matters is a notorious drug-trafficking group, the Gaitanist Self-Defense Forces, whose control over northern Colombia is 'so complete that the country’s ombudsman’s office calls the group the region’s “hegemonic” armed actor," according to the report.

Are the actual profits much higher?

As Mike Shedlock of Mish Talk notes;

Biden vowed to “end the illicit movement” of people through the Darién jungle in Columbia. But the profits are too big to pass up. A record 360,000 made passage this year. That’s well above the record 250,000 for all of 2022.

The Math

- $170 * 360,000 = $61,200,000

- $500 * 360,000 = $180,000,000

The Colombian politicians and helpers have made somewhere between $61 million and $180 million this year selling services that the Biden administration vowed to end.

Once Through Darien, Then What?

There is much more to the article. Importantly, once through the Darien Gap, everyone is on their own.

“On the Panamanian side, small criminal bands rove the forest, using rape as a tool to extract money and punish those who cannot pay,” notes the New York Times.

People need to cough up more money to make it through Panama to Mexico, then from Mexico to the US border, then still more money from the US border to the US.

People without adequate funds are subject to rape or torture or death.

This is what’s become of US immigration policy.

As migrants from Central America surge north in hopes of reaching the porous US border, businessmen and elected officials have turned the journey into a well-oiled, and profitable, machine – making “tens of millions” of dollars per year (or more, see below).

The Darién Gap, once a formidable natural barrier between North and South America, has essentially become a marketplace. Remote and beautiful, a constellation of small towns leading to the gap has been become a hub for mass migration, according to the NY Times.

The towns are riddled with poverty, and are housing a population that has long been victims of the country’s internal conflicts. Their sewage, water, and electricity systems, already frail, were overwhelmed when thousands of Haitians began to show up in 2021, fleeing the chaos that spiraled after their President’s assassination.

The Darién Gap has quickly morphed into one the Western Hemisphere’s most pressing political and humanitarian crises. A trickle only a few years ago has become a flood: More than 360,000 people have already crossed the jungle in 2023, according to the Panamanian government, surpassing last year’s almost unthinkable record of nearly 250,000.

In response, the United States, Colombia and Panama signed an agreement in April to “end the illicit movement of people” through the Darién Gap, a practice that “leads to death and exploitation of vulnerable people for significant profit.” -NY Times

Opportunists seize the day

“This is a beautiful economy,” said Fredy Marín, a former town councilman from the municipality of Necoclí, who operates a boat company that ferries migrants on their way to the US. Marín says he moves thousands of people per month for $40 per head.

Marín is now running for mayor of Necoclí, where he’s vowed to preserve the thriving migration industry, which has led to locals selling essentials like tents, snake repellent, and even toddler-sized rubber boots to migrants.

Elected community board members, like Darwin García in Acandí, Colombia, even describe the explosion of migrants as the “best thing” for their struggling communities.

“We have organized everything: the boatmen, the guides, the bag carriers,” said García, who added that the flood of “migrants the best thing that could have happened” to their impoverished town. García’s younger brother, Luis Fernando Martínez, is running for mayor of Acandí on this platform of sustaining the so-called ‘migration economy.’

The migrants can even hire a sort of “security” service from groups like the New Light Darién Foundation, which offers a guided journey for migrants navigating the gap.

The foundation has hired more than 2,000 local guides and backpack carriers, organized in teams with numbered T-shirts of varying colors — lime green, butter yellow, sky blue — like members of an amateur soccer league.

Migrants pay for tiers of what the foundation calls “services,” including the basic $170 guide and security package to the border. Then a migration “adviser” wraps two bracelets around their wrists as proof of payment. -NY Times

The service is “Like a ticket to Disney,” said Renny Montilla, 25, a construction worker from Venezuela.

Whose fault is this?

On the surface, Colombian and U.S. governments have expressed commitments to curb this illicit flow. However, actions on the ground tell a different story. Colombia’s President Gustavo Petro says the United States caused this migration crisis while showing no interest in curbing it, and says that the roots of this migration were “the product of poorly taken measures against Latin American peoples.”

The New York Times has spent months here in the Darién Gap and surrounding towns, and the national government has, at best, a marginal presence.

When the national authorities can be seen at all, they are often waving migrants through, or in the case of the national police, fist-bumping the men selling expensive travel packages through the jungle.

The top police official in the region, Col. William Zubieta, said it wasn’t his job to halt the flow. Instead, he argued, the nation’s migration authorities should be exerting control.

“Unfortunately, they do not have it,” he said.

…

He [Petro] said he had no intention of sending “horses and whips” to the border to solve a problem that wasn’t of his country’s making.

In the absence of the Colombian government, local leaders have decided to handle migration themselves. -NY Times

Further complicating matters is a notorious drug-trafficking group, the Gaitanist Self-Defense Forces, whose control over northern Colombia is ‘so complete that the country’s ombudsman’s office calls the group the region’s “hegemonic” armed actor,” according to the report.

Are the actual profits much higher?

As Mike Shedlock of Mish Talk notes;

Biden vowed to “end the illicit movement” of people through the Darién jungle in Columbia. But the profits are too big to pass up. A record 360,000 made passage this year. That’s well above the record 250,000 for all of 2022.

The Math

- $170 * 360,000 = $61,200,000

- $500 * 360,000 = $180,000,000

The Colombian politicians and helpers have made somewhere between $61 million and $180 million this year selling services that the Biden administration vowed to end.

Once Through Darien, Then What?

There is much more to the article. Importantly, once through the Darien Gap, everyone is on their own.

“On the Panamanian side, small criminal bands rove the forest, using rape as a tool to extract money and punish those who cannot pay,” notes the New York Times.

People need to cough up more money to make it through Panama to Mexico, then from Mexico to the US border, then still more money from the US border to the US.

People without adequate funds are subject to rape or torture or death.

This is what’s become of US immigration policy.

Loading…