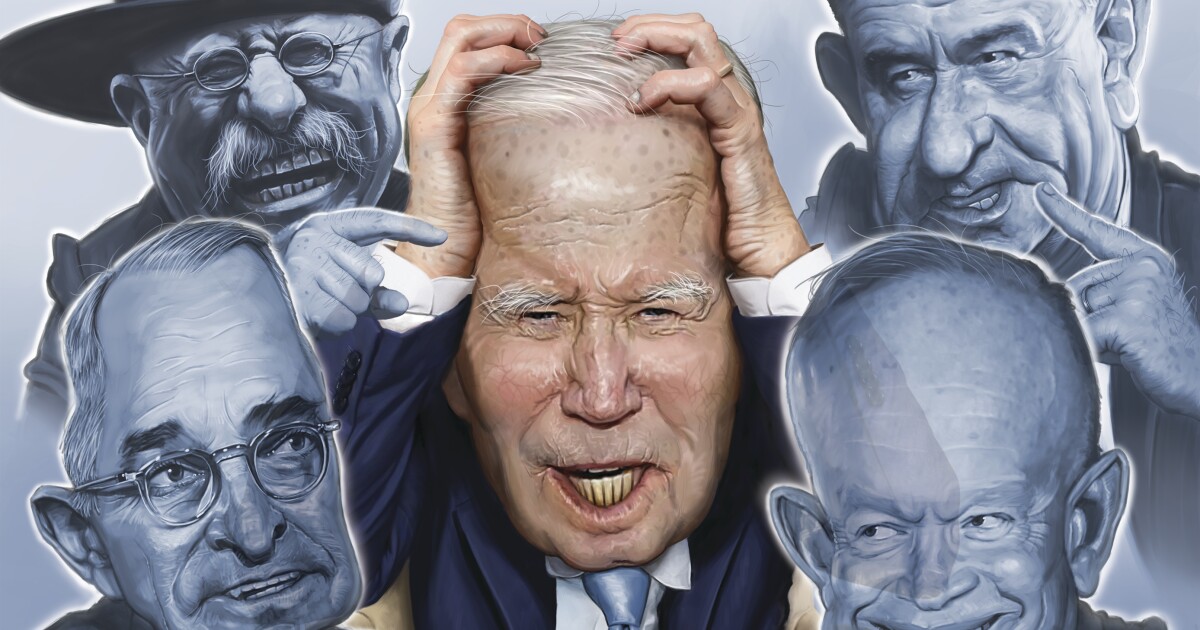

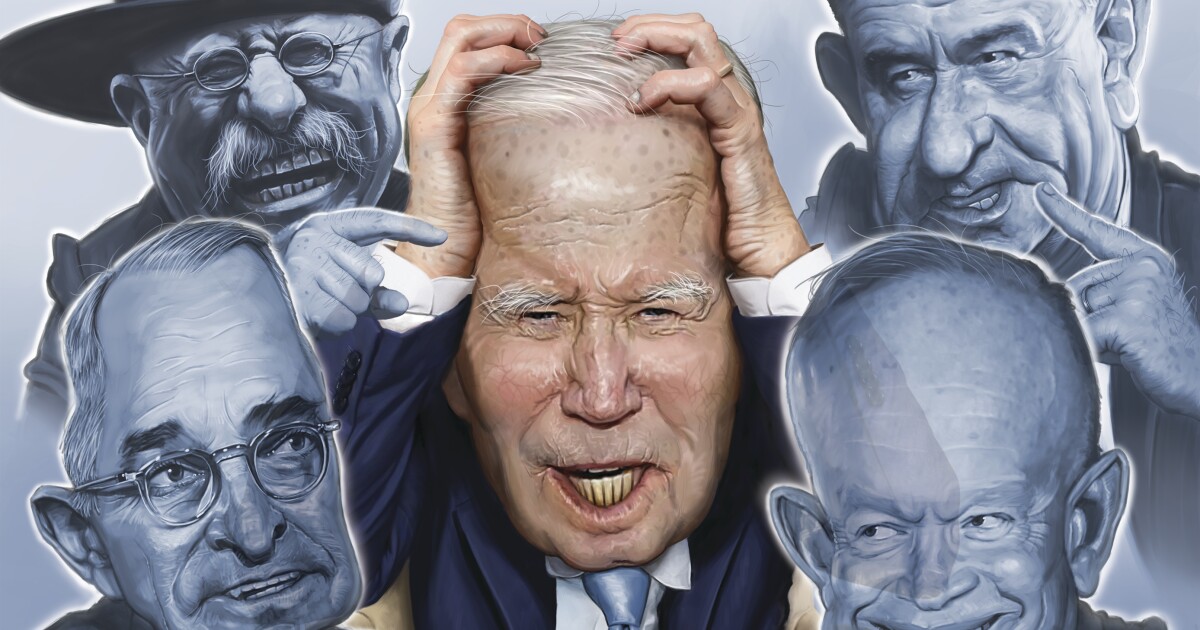

Democrats are anxious over a recent poll showing that nearly two-thirds of Democrats do not want President Joe Biden to run again. Worse still, from their perspective, is the survey’s finding that Biden is trailing in a head-to-head matchup against his likely Republican opponent. The feeling is bipartisan: 70% of voters don’t think Biden should run for reelection.

Yet Biden remains undeterred. And if the president is simply trying to wait out the doubters until his candidacy becomes inevitable, he might need a new strategy: History shows that many past presidents have both mulled and even chosen to drop out of the race later in the cycle than we are now.

WHY RALPH NADER IS BACKING BIDEN OVER ALTERNATIVE CANDIDATES IN 2024 RACE

In 1904, Teddy Roosevelt was serving as president after replacing the assassinated William McKinley. At the time, succeeding vice presidents did not have a record of winning the presidency on their own: Chester A. Arthur, Andrew Johnson, and John Tyler all had failed to secure the presidency on their own after stepping in as replacements. Roosevelt ran again and won, breaking the streak of unsuccessful succeeding vice presidents. In doing so, though, he did something that tied his hands for 1908. After the election victory, Roosevelt announced that “the wise custom which limits the President to two terms regards the substance and not the form. Under no circumstances will I be a candidate for or accept another nomination.”

Roosevelt later regretted his announcement. At one point, he even said, “I would cut my hand off right there if I could recall that written statement.” Making a commitment is one thing, though. Sticking to it was another. Throughout his second term, he was looking for a successor but was not making his intentions sufficiently clear. He discussed the possibility of his friend and Secretary of War William Howard Taft taking over in a March 9, 1906, Cabinet meeting. The Cabinet went along, but Roosevelt still did not announce publicly for Taft, telling his son Kermit of his desire that the GOP “shall be able to nominate Taft for president. Of course, this is to be kept strictly quiet as I cannot, as president, take any part in getting him the nomination.” He did tell Taft, sort of, inviting him and his wife, Nellie, to dinner at the White House. Even here, he was vague, telling them, “I am the seventh son of a seventh daughter. I have clairvoyant powers. I see a man before me weighing 350 pounds. There is something hanging over his head. I cannot make out what it is. It is hanging by a slender thread. At one time, it looks like the presidency — then again, it looks like the chief justiceship.” Nellie said, “Make it the presidency!” Taft, who long harbored other aspirations, said, “Make it the chief justiceship.” (Taft would later become chief justice in 1921, after his presidency.)

Roosevelt remained publicly quiet about his decision until late 1907. His aide William Loeb told Roosevelt to make an announcement or voters would assume he was running again. Even at this late date, Roosevelt considered other possible candidates before telling Loeb, “We had better turn to Taft. … See Taft … and tell him … so that he will know my mind.” When Taft came to see Roosevelt and thank him for making it official, Roosevelt patted him on the back and said, “Yes, Will, it’s the thing to do.”

On Nov. 19, 1907, Roosevelt sent a note to the secretary of the treasury, the postmaster general, and the secretary of the interior that said, “Advocacy of my renomination or acceptance of an election as a delegate for that purpose, will be regarded as a serious violation of official propriety and will be dealt with accordingly.” On Dec. 30, 1907, Taft gave a speech in Boston that is generally seen as the beginning of his presidential campaign. Roosevelt’s reluctance to commit until late 1907 revealed a conflicted mind. Taft did indeed win the presidency, but Roosevelt was disappointed in the Taft presidency. In 1912, Roosevelt unsuccessfully challenged Taft for the Republican nomination. Upon losing, Roosevelt then ran as a third-party candidate, spoiling his old friend’s chances and allowing Woodrow Wilson to become president.

Roosevelt’s cousin, Franklin Delano Roosevelt, also faced the decision of whether to run again twice, in 1940 and 1944. In 1940, Roosevelt was tired and considered stepping down, but the advent of World War II and the fall of France that June made the decision to run for an unprecedented third term more likely. Roosevelt did not see anyone on the Democratic bench who he felt could step in, with the possible exception of Secretary of State Cordell Hull.

On July 3, 12 days before the Democratic National Convention, Roosevelt met with Hull to discuss the possibility of Hull running. Hull had initially thought he would have Roosevelt’s backing but recognized that Roosevelt had already decided to run again and begged off, citing health concerns. On July 7, a week before the convention, Roosevelt lunched with political adviser James Farley at Hyde Park and told him that the war put him in a situation in which he had to run, adding that if he were to announce that he was not running, then “it would have destroyed his effectiveness as the leader of this nation.”

In 1944, a noticeably older Roosevelt faced the decision to run again for an again unprecedented fourth term. Roosevelt was by now sickly — his political ally Ed Flynn later recalled that “I felt that he would never survive the term” and asked as a friend that Roosevelt consider not running again. Furthermore, there was once again the question of who would replace him. Vice President Henry Wallace was unacceptable. He was unpopular within many factions of the Democratic Party and even less popular nationally. According to a September 1943 Gallup poll, Wallace would have lost the election to Republican New York Gov. Thomas Dewey, the eventual challenger, by a 60-40 spread.

Roosevelt being Roosevelt, he kept his cards close to his chest. But on July 11, 1944, Roosevelt bowed to the inevitable and told reporters at a press conference that DNC Chairman Robert Hannegan had sent him a letter telling him that he had a majority of the delegates poised to vote for his renomination at the DNC. Faced with this support from the party, he read his response to the reporters, an anti-Shermanesque statement that said, in part, “If the Convention should carry this out, and nominate me for the Presidency, I shall accept. If the people elect me, I will serve.” With that decision made, the delegates selected Missouri Sen. Harry Truman, one of two candidates Roosevelt said he would support, on the third ballot to be the running mate. It was a good thing, too, as Roosevelt died on April 12, 1945, and we would later learn that Wallace was not only sympathetic to the Soviet Union, but he had actual Soviet agents on his staff.

Truman took over for Roosevelt and successfully ran again in 1948. But in early 1952, Truman was languishing with a 23% approval rating. Truman claimed in his memoirs that he had decided in 1950 not to run again, following consultations with his wife, Bess. He also told his staffers in November 1951 that he did not plan to run again, swearing them to secrecy. But when Truman’s name was placed on the ballot for the New Hampshire primary in the spring of 1952, he did not have it removed. On March 11, he lost the primary to Tennessee Sen. Estes Kefauver, 55% to 44%. On March 29, Truman told the attendees at the Jefferson-Jackson Day Dinner that he would not run again: “I shall not be a candidate for reelection. I have served my country long, and I think efficiently and honestly. I shall not accept a renomination. I do not feel that it is my duty to spend another four years in the White House.” Kefauver did not win the nomination, however. Illinois Gov. Adlai Stevenson captured the Democratic slot but went on to lose to Dwight Eisenhower in 1952.

Eisenhower did not have a popularity problem, but he did have a health concern. Eisenhower had a serious heart attack on Sept. 24, 1955, which prompted him to consider whether he wanted to run again. Once again, there were concerns about whether anyone could replace him. He feared that another Dewey candidacy would divide the party, that Vice President Richard Nixon was not yet ready. Eisenhower planned a Jan. 11, 1956, dinner to ask the question, “Should I run again?” The carefully selected guest list included four Cabinet members, five staffers, and three outside advisers, but not Nixon. Word of the dinner leaked to the press, and the Eisenhower team blamed the uninvited vice president for the breach. The dinner was rescheduled for Jan. 13, two days later. At the dinner, everyone urged Eisenhower to run again, with the exception of Milton Eisenhower, who was concerned about his brother’s health.

The dinner broke up at 11:15 p.m. without a decision. On Jan. 19, Eisenhower told the press that he needed more time “in order that I may reach a logical decision. I will do it as soon as I can.” A positive report from his doctor in mid-February eased his health concerns. On Feb. 29, 1956, Eisenhower told the press that if nominated and elected, “my answer will be positive, that is, affirmative.” As for Nixon, Eisenhower let him dangle for two more months, until April 25, before revealing that Nixon would be his choice as running mate.

Like Eisenhower, Lyndon Johnson had also had a heart attack in the 1950s. He was only 46 when it happened, in 1956, but he smoked three packs of cigarettes a day. Twelve years later, when Johnson was approaching the last year of his first full term as president, he was concerned about both his health and the United States’s increasingly bloody involvement in Vietnam. Like Truman, Johnson later claimed that he had decided early in his term not to run again. National security adviser Walt Rostow recalled Johnson saying to senior aides in October 1967, “I don’t want any of you to plan in terms of my being a candidate next year.” Still, like Truman, Johnson also allowed his name to remain on the ballot in the New Hampshire primary.

On March 12, 1968, Oregon Sen. Eugene McCarthy shocked the political world by getting 42% of the vote in the New Hampshire primary, holding Johnson under a majority with 48%. A few weeks after this poor showing, on March 31, 1968, Johnson gave a surprise announcement at the end of a televised address that he would “neither seek nor accept” the Democratic nomination for president. Perhaps he had never intended to run again, but the New Hampshire result certainly affected his announcement timing.

The last president seriously to consider not running for a second term was Ronald Reagan. His wife, Nancy, wanted him to quit, especially after the near-miss assassination attempt of March 30, 1981. She was also concerned about his age: Reagan was 72 at the start of 1984 — the oldest president at the time. In May 1983, Reagan had not given Sen. Paul Laxalt permission to start a reelection campaign effort. A reluctant Nancy eventually said, “If you feel that strongly, go ahead. You know I’m not crazy about it, but OK.” In October, he OKed the first steps toward reelection and announced that he would run again on Jan. 29, 1984. Reagan then won an easy reelection effort against Walter Mondale.

So much of this history relates to the situation in which Biden finds himself now. Sure, he has already announced a run, but others have dropped out later in the process. The question of presidential indecision “freezing the field” is a concern as well. Presumably, Gov. Gavin Newsom (D-CA) would enter the field if Biden balked at running again, as would Gov. J.B. Pritzker (D-IL), among others. As for the vice president question, Kamala Harris has underperformed and is unpopular, which may be a reason that Biden has not stepped aside. But Biden running again at 82 only increases the likelihood that Harris could end up as president. As Eisenhower learned, it is difficult to have a decision-making process with the vice president and successor lurking in place.

CLICK HERE TO READ MORE FROM THE WASHINGTON EXAMINER

There is also the question of what his advisers are telling him. History has shown that advisers usually want the president to stay as they are loath to give up their own positions of influence. Sometimes, it is only close relatives, be it a spouse or a sibling, who are willing to tell the president what he may not want to hear.

Finally, there is the question of timing. Biden has already said that he is running again, but three presidents, Teddy Roosevelt, Truman, and Johnson, all made at least some move toward running and yet announced their decisions not to go ahead later in the process than we are now. And while Franklin Roosevelt eventually decided to run again in 1944, perhaps he should not have, given how frail and close to death he was. Presidents always think they are irreplaceable, but the nation moves on. Even if Biden has made his decision, history shows it’s not too late to reconsider.

Contributing writer Tevi Troy is the director of the Presidential Leadership Project at the Bipartisan Policy Center and a former White House aide. He is the author of four books on the presidency, including, most recently, Fight House: Rivalries in the White House from Truman to Trump.