Authored by Terri Wu via The Epoch Times (emphasis ours),

Foreign investments are leaving China.

Half of the $250 billion to $300 billion foreign bond investments since 2019 have exited, and U.S. private equity and venture capital investments in China have fallen by more than 50 percent, according to a JP Morgan report last month.

Foreign direct investment into China in the second quarter of this year reached a 25-year low at $4.9 billion, with a year-on-year decline of 87 percent, according to Chinese official data.

Bloomberg and fDi Markets data on new investment projects—a more telling indicator of whether foreign firms are still investing in the country—show a 40 percent drop, to $74 billion in 2020 from $120 billion in 2019, and an additional 45 percent decline to $41 billion in 2022—the lowest since 2010.

Although financial transactions are easy to track without much lag, it may take years for foreign direct investment data to reflect Western firms' diversifying away from China.

For this reason, Beijing might be unaware of how bad things really are as far as foreign direct investment, analysts of the Rhodium Group, a leading research firm on the Chinese economy, warned in a recent report.

“Amidst a broader structural slowdown in China’s economy, the delayed reactions could contribute to further losses in productivity and economic growth,” the report stated.

The implied assumption here is that preventing economic losses is a priority for the Chinese Communist Party (CCP). However, some China experts challenge this.

“It's not that Xi Jinping and the CCP leadership hate economic growth—it's just not a priority,” Derek Scissors, chief economist of research firm China Beige Book and a senior fellow at the Washington-based think tank American Enterprise Institute, told The Epoch Times.

“The priority is control over the society, including the economy. So whenever there's a trade-off between economic control and growth, they choose control,” he said.

“And when we say, ‘Oh, you know, you could be growing faster. Why are you doing these things?’ The answer is obvious: It’s because that's not their priority.”

Mr. Scissors and other experts told The Epoch Times that overall economic growth isn’t at the top of the agenda for Chinese regime leader Xi Jinping. Instead, China is, by design, going through a paradigm shift in how it interacts with the global economy and is screening and filtering for foreign investors loyal to Mr. Xi.

As a result, China's overall political and business landscape defies past experience, they said, and Western interpretations will make the wrong assumptions on China—even more so than before.

3 Phases of Foreign Direct Investment

When U.S. Commerce Secretary Gina Raimondo visited China in August, she warned that the country could become “uninvestable” if the unpredictable official behavior, such as raids on U.S. firms, don't cease. This year, Mintz Group’s Beijing office was raided in March, Bain & Co.’s Shanghai office in April, and Capvision Partners’s offices in multiple cities in May.

The Chinese business environment for U.S. companies wasn't always like this.

Mike Sun, a U.S.-based businessman with decades of experience advising foreign investors and traders doing business in China, recalled that the first generation of U.S. investors visited mainland China with a pioneering spirit. He spoke to The Epoch Times using an alias to protect his business in China.

In the early 1990s, he said a Jewish American businessman told him, “I want to be America’s Marco Polo,” referring to the Italian explorer who introduced Europeans to China. The businessman spoke fluent Mandarin and was married to a Chinese woman.

Back then, China was full of opportunities.

If investing in China in those years felt like an adventure, it became a no-brainer the next decade, from 2000 to 2012. One would have been foolish not to invest in China, Mr. Sun recalled.

The crowning glory for the communist regime was the 2008 Beijing Olympics, he said. When U.S. President George W. Bush and his family sat next to Chinese Foreign Minister Yang Jiechi at the China–United States basketball game, it became a symbol of the international community's acceptance of the CCP.

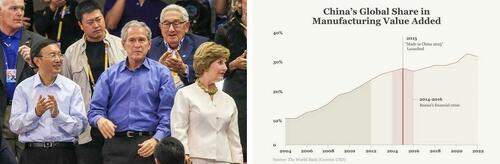

China had become the "world’s factory" after it joined the World Trade Organization in 2001. According to World Bank data, its share of global manufacturing value-add rose from 9 percent in 2004 to 22 percent in 2012 and 30 percent in 2022.

But Mr. Xi’s ascension in March 2013 heralded a different decade. In 2015, the leader started his industrial “Made in China 2025” plan, aiming for global dominance in advanced manufacturing sectors such as semiconductors and new energy.

To achieve this goal, the regime encouraged large-scale technology theft from Western countries.

In Mr. Sun’s view, Mr. Xi has reversed China’s integration into the rest of the world, a trend that had defined the previous two decades.

“Xi doesn’t want China to be a second Russia,” Mr. Sun said.

Between 2014 and 2016, Russia suffered a financial crisis because of the sharp price decline of crude oil, a major export, and international sanctions as a result of its annexation of Crimea. Since then, Russia’s growth prospects have remained bleak because of challenges in diversifying its main industries and ongoing Western sanctions, according to European think tank Bruegel.

After Russia invaded Ukraine in February 2022, it was hit with more than 13,000 restrictions. The sanctions have severed Russia from advanced technology sectors abroad and forced the nation to resort again to energy commodities trading to sustain its economy growth, according to findings by the Carnegie Endowment for International Peace, a Washington-based think tank.

Mr. Sun said China’s changes have become more apparent in the past two to three years, coinciding with the COVID-19 pandemic, during which Mr. Xi largely completed his consolidation of power.

That’s what Meng Jun, a Chinese entrepreneur, said he experienced.

Mr. Meng had a rubber product business with an annual revenue of $15 million. In 2021, when the rest of the world reopened, his factory in Nanning, the capital of southern China’s Guangxi Province, began to receive orders again. However, he couldn't resume production because of the regime’s COVID-19 lockdowns.

Initially, he was able to bribe local officials so his factory could run at night while other factories had to remain shut. But later, no one would bend the rules because the officials didn’t want to lose their jobs over the possibility that a COVID-19 case would be traced back to an unauthorized factory operating under China’s zero-COVID policy. He lost millions.

He closed the business last year and left for the United States.

Read more here...

Authored by Terri Wu via The Epoch Times (emphasis ours),

Foreign investments are leaving China.

Half of the $250 billion to $300 billion foreign bond investments since 2019 have exited, and U.S. private equity and venture capital investments in China have fallen by more than 50 percent, according to a JP Morgan report last month.

Foreign direct investment into China in the second quarter of this year reached a 25-year low at $4.9 billion, with a year-on-year decline of 87 percent, according to Chinese official data.

Bloomberg and fDi Markets data on new investment projects—a more telling indicator of whether foreign firms are still investing in the country—show a 40 percent drop, to $74 billion in 2020 from $120 billion in 2019, and an additional 45 percent decline to $41 billion in 2022—the lowest since 2010.

Although financial transactions are easy to track without much lag, it may take years for foreign direct investment data to reflect Western firms’ diversifying away from China.

For this reason, Beijing might be unaware of how bad things really are as far as foreign direct investment, analysts of the Rhodium Group, a leading research firm on the Chinese economy, warned in a recent report.

“Amidst a broader structural slowdown in China’s economy, the delayed reactions could contribute to further losses in productivity and economic growth,” the report stated.

The implied assumption here is that preventing economic losses is a priority for the Chinese Communist Party (CCP). However, some China experts challenge this.

“It’s not that Xi Jinping and the CCP leadership hate economic growth—it’s just not a priority,” Derek Scissors, chief economist of research firm China Beige Book and a senior fellow at the Washington-based think tank American Enterprise Institute, told The Epoch Times.

“The priority is control over the society, including the economy. So whenever there’s a trade-off between economic control and growth, they choose control,” he said.

“And when we say, ‘Oh, you know, you could be growing faster. Why are you doing these things?’ The answer is obvious: It’s because that’s not their priority.”

Mr. Scissors and other experts told The Epoch Times that overall economic growth isn’t at the top of the agenda for Chinese regime leader Xi Jinping. Instead, China is, by design, going through a paradigm shift in how it interacts with the global economy and is screening and filtering for foreign investors loyal to Mr. Xi.

As a result, China’s overall political and business landscape defies past experience, they said, and Western interpretations will make the wrong assumptions on China—even more so than before.

3 Phases of Foreign Direct Investment

When U.S. Commerce Secretary Gina Raimondo visited China in August, she warned that the country could become “uninvestable” if the unpredictable official behavior, such as raids on U.S. firms, don’t cease. This year, Mintz Group’s Beijing office was raided in March, Bain & Co.’s Shanghai office in April, and Capvision Partners’s offices in multiple cities in May.

The Chinese business environment for U.S. companies wasn’t always like this.

Mike Sun, a U.S.-based businessman with decades of experience advising foreign investors and traders doing business in China, recalled that the first generation of U.S. investors visited mainland China with a pioneering spirit. He spoke to The Epoch Times using an alias to protect his business in China.

In the early 1990s, he said a Jewish American businessman told him, “I want to be America’s Marco Polo,” referring to the Italian explorer who introduced Europeans to China. The businessman spoke fluent Mandarin and was married to a Chinese woman.

Back then, China was full of opportunities.

If investing in China in those years felt like an adventure, it became a no-brainer the next decade, from 2000 to 2012. One would have been foolish not to invest in China, Mr. Sun recalled.

The crowning glory for the communist regime was the 2008 Beijing Olympics, he said. When U.S. President George W. Bush and his family sat next to Chinese Foreign Minister Yang Jiechi at the China–United States basketball game, it became a symbol of the international community’s acceptance of the CCP.

China had become the “world’s factory” after it joined the World Trade Organization in 2001. According to World Bank data, its share of global manufacturing value-add rose from 9 percent in 2004 to 22 percent in 2012 and 30 percent in 2022.

But Mr. Xi’s ascension in March 2013 heralded a different decade. In 2015, the leader started his industrial “Made in China 2025” plan, aiming for global dominance in advanced manufacturing sectors such as semiconductors and new energy.

To achieve this goal, the regime encouraged large-scale technology theft from Western countries.

In Mr. Sun’s view, Mr. Xi has reversed China’s integration into the rest of the world, a trend that had defined the previous two decades.

“Xi doesn’t want China to be a second Russia,” Mr. Sun said.

Between 2014 and 2016, Russia suffered a financial crisis because of the sharp price decline of crude oil, a major export, and international sanctions as a result of its annexation of Crimea. Since then, Russia’s growth prospects have remained bleak because of challenges in diversifying its main industries and ongoing Western sanctions, according to European think tank Bruegel.

After Russia invaded Ukraine in February 2022, it was hit with more than 13,000 restrictions. The sanctions have severed Russia from advanced technology sectors abroad and forced the nation to resort again to energy commodities trading to sustain its economy growth, according to findings by the Carnegie Endowment for International Peace, a Washington-based think tank.

Mr. Sun said China’s changes have become more apparent in the past two to three years, coinciding with the COVID-19 pandemic, during which Mr. Xi largely completed his consolidation of power.

That’s what Meng Jun, a Chinese entrepreneur, said he experienced.

Mr. Meng had a rubber product business with an annual revenue of $15 million. In 2021, when the rest of the world reopened, his factory in Nanning, the capital of southern China’s Guangxi Province, began to receive orders again. However, he couldn’t resume production because of the regime’s COVID-19 lockdowns.

Initially, he was able to bribe local officials so his factory could run at night while other factories had to remain shut. But later, no one would bend the rules because the officials didn’t want to lose their jobs over the possibility that a COVID-19 case would be traced back to an unauthorized factory operating under China’s zero-COVID policy. He lost millions.

He closed the business last year and left for the United States.

Read more here…

Loading…