Authored by Hal Brands, op-ed via Bloomberg.com,

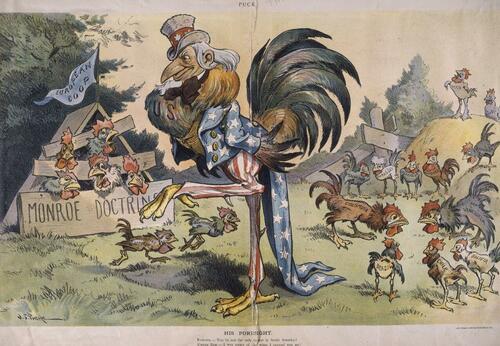

The Monroe Doctrine is disparaged in Washington and Latin America, but it remains the foundation of the liberal international order the US leads today...

“I believe strictly in the Monroe Doctrine, in our Constitution and in the laws of God,” one American religious leader declared in 1923. That same year, 10 million American schoolchildren were subjected to a centennial recitation of President James Monroe’s famous doctrine in class.

“The American continents, by the free and independent condition which they have assumed and maintain, are henceforth not to be considered as subjects for future colonization by any European powers,” Monroe said in December 1823. For generations thereafter, that statement was a cardinal principle of US policy. It fused America’s founding ethos of anti-imperialism to the fierce nationalism and outrageous ambition that ultimately allowed the country to surpass every empire on Earth. It even became central to the America’s understanding of itself.

There have been no such celebrations this weekend to mark the 200th birthday. Most Latin American observers consider the Monroe Doctrine an imperial imposition. Even US officials now see it as an embarrassing anachronism. “The era of the Monroe Doctrine is over,” said Secretary of State John Kerry in 2013. Yet two centuries after it was issued, that policy remains more relevant than many might like to admit.

The Monroe Doctrine is a reminder that America’s strategic interests have always been intertwined with its revolutionary values. It represents the regional foundation of the liberal international order the US leads today. And although American policymakers often say the Monroe Doctrine is dead, they don’t — or shouldn’t — really mean it.

The Western Hemisphere was once an imperial battleground. At the start of the 1820s, Spain’s empire stretched from California to the Tierra del Fuego. Britain had territories and interests from Canada to Chile. France was clinging to imperial fragments around the Caribbean; Portugal was trying, vainly, to keep Brazil. Russia’s holdings included Alaska and outposts farther south. Powerful empires sought advantage in the Americas — and tried to keep a subversive republican newcomer well contained.

In 1823, America’s strategic landscape was menacing. The collapse of Spanish and Portuguese empires in Latin America was birthing new nations. But a coalition of European monarchies — the Holy Alliance of Austria, Prussia and Russia — was considering intervention to recolonize those countries; just two years earlier Russia had threatened a push down North America’s Pacific Coast. The Western Hemisphere was potentially facing a two-pronged absolutist assault. The US would then be surrounded by hostile, antidemocratic empires, foreclosing its future expansion and perhaps threatening its survival.

Monroe’s answer, drafted by Secretary of State John Quincy Adams, combined self-assertion with self-denial. Monroe warned European powers not to seek new colonies in the Western Hemisphere (implicitly counting on Britain, which also opposed its rivals’ expansion, to enforce that ban), pledging that America, in return, would steer clear of Old World conflicts. After a slow start, Washington ultimately honored the first part of the doctrine more faithfully than the second.

By the mid-19th century, the US had foreclosed European expansion in North America by taking much of the continent itself. Washington then began pushing European powers out of its neighborhood, forcibly evicting Spain from the Caribbean in 1898. During the early 20th century, the US intervened in unstable nations from Nicaragua to Haiti, primarily to deprive prowling Europeans of chances to meddle. Over the subsequent decades, Washington beat back challenges from countries — Imperial Germany, Nazi Germany and the Soviet Union — that sought Latin American footholds amid the epic global clashes that defined the age.

No other country in the modern era has dominated its surrounding region so thoroughly, and for so long, as the US. In this sense, America denied imperial prerogatives to its rivals, only to claim them for itself. But it is ironic that the doctrine is now considered a historical relic — because it continues to influence the long arc of US statecraft around the globe.

First, the Monroe Doctrine asserted an enduring principle of US strategy — that America requires a balance of power that favors liberalism. “It is impossible,” Monroe declared, “that the allied powers should extend their political system” — monarchy — to the Western Hemisphere “without endangering our peace and happiness.”

This wasn’t some rhetorical flourish. America’s founding struggle had been a revolt against monarchy. Its republican government cast it, immediately, into sharp ideological conflict against Europe’s absolutist regimes. So Monroe was simply explaining that the US could not flourish in an environment ruled by regimes that were inherently, even existentially, hostile to its liberal experiment. Nearly a century later, President Woodrow Wilson argued more or less the same thing in calling on his country to make a “world safe for democracy” in World War I.

The Monroe Doctrine also enshrined a related American tradition — hostility to rival spheres of interest. The modern era has seen the astounding growth of a US sphere of interest that began in North America and now reaches around the globe. Yet American leaders have never been as comfortable with other powers, especially autocratic powers, carving out their own domains.

Such arrangements, Monroe said, could be established only by coercion: Free peoples would never accept them “of their own accord.” Autocratic empires, whether in the Americas or elsewhere, would serve as platforms for subversion, intimidation and aggression against the world beyond. Since the early 20th century, America has fought hot wars and cold wars to keep Eurasian autocracies from establishing globe-threatening spheres of interest in their own regions — an extension of Monroe’s doctrine, but one he and Adams would have understood.

Finally, the Monroe Doctrine established the regional primacy that underpins America’s global power. If the US faced serious threats close to home, it would have to deploy vast armies to defend its long land borders. But if America faced no major threats within the Western Hemisphere, it would be free, eventually, to roam the world. Which means that the quasi-imperialistic Monroe Doctrine was vital to the liberal order the US eventually built.

A country plagued by nearby challenges could not have intervened three times, in the two world wars and the Cold War, to prevent autocratic powers from dominating Eurasia. It could not have secured overseas regions through globe-spanning alliances after 1945. It could not have anchored a thriving international economy and helped democracy spread more broadly than ever before.

America’s enemies understood this: Imperial Germany, Nazi Germany, and the Soviet Union all meddled in the Western Hemisphere because they knew that keeping the US preoccupied was essential to imposing their own, darker visions on the world.

The Monroe Doctrine cast its share of darkness, of course. The tools of US primacy included military interventions in Central America and the Caribbean; coups, covert action and aid for ugly counterinsurgencies in countries throughout the region; and land grabs in strategic points like Puerto Rico and the Panama Canal Zone. Hegemony is a messy business. No country can dominate a vast region while keeping its hands entirely clean.

When other powers pursued regional empires, in fact, they invoked US policy as their guide. Japan portrayed its aggression in China in the 1930s as a sort of Asian Monroe Doctrine. Today, when Chinese expansionists advocate “Asia for Asians,” or call Central Asia “China’s Latin America,” they are making, explicitly or implicitly, a similar claim. The truth is a bit more complicated.

Whatever its failings, the Monroe Doctrine did — with tacit support from the British Royal Navy — gradually curtail formal European colonialism in Latin America, an achievement of real value to the independent countries of the region. In the 20th century, moreover, a hemisphere free of US imperialism might well have been more susceptible to fascist or communist influence.

True, during the Cold War especially, the US protected its regional position through cooperation with friendly dictators. But preventing countries from going communist at least preserved the possibility they would later evolve toward democracy — as many eventually did, once their economies matured and the politics stabilized, in the 1970s and 1980s. The US placed itself firmly behind this democratic movement: Which of America’s great-power rivals would have done that?

American primacy has had other benefits. The fact that Latin America — a region suffused, sadly, with internal violence — has seen so little interstate conflict in the past century might, perhaps, testify to the role of US power in enforcing a hegemonic peace. Not least, insofar as Latin America has benefitted from the larger liberal order — one in which trade has surged, living standards have increased and global wars have been avoided for the last 80 years — it has also benefitted from the US regional supremacy that has enabled a degree of global progress.

Whatever the costs and benefits, the Monroe Doctrine long ago came to look like an imperial remnant in a post-imperial age. US officials mostly stopped publicly invoking the doctrine after a regionally polarizing CIA intervention in Guatemala in 1954. When Secretary of State Rex Tillerson mentioned the doctrine favorably in 2018, his comments were mostly treated as a costly gaffe. A policy Americans had once venerated now seemed painfully out of date.

True, after the Cold War, it had certainly seemed unnecessary. With US power unchallenged, with markets and democracy sweeping the region, everything was going Washington’s way. That’s no longer the case.

For years, the region’s politics have been deteriorating.

In Venezuela, Nicaragua and other countries, illiberal populists have set about destroying democratic norms and institutions. Democracy is fragile and political instability is rising across much of the region.

Peru is on its fourth president in the last three years; Argentina has elected a Donald Trump acolyte who promises to take a chainsaw to the political system. Mexico, which not long ago was moving toward stronger democracy and better ties with Washington, has regressed in both dimensions under Andrés Manuel López Obrador. Economic challenges often exacerbate political problems: Covid battered societies that were already suffering from high levels of economic insecurity.

Meanwhile, the US — which, since the 1990s, has seen the region primarily through the lens of illegal drugs and immigration — has been bleeding influence. And given that every great-power rivalry of the modern era has ensnared the Western Hemisphere, the bill for that strategic neglect is coming due.

One US antagonist, Russia, is forging anti-American alliances by making common cause with the region’s most thuggish leaders. When, in 2019, there was talk of US intervention in Venezuela to end the humanitarian catastrophe of Nicolas Maduro’s repressive rule, Russian military contractors raced to the country to protect his regime.

Russian weapons and intelligence support have bolstered another anti-American dictator, Nicaragua’s Daniel Ortega. Russian sniper rifles were used to kill pro-democracy protestors in 2018; Moscow and Managua have pursued cyber-cooperation to surveil and suppress Nicaragua’s opposition. Russian propaganda and disinformation fuel anti-US sentiment in Latin America and around the globe.

Russia’s presence in Latin America remains modest in comparison to the Cold War. But it is supporting states that brutalize their people and oppose US influence as part of a larger “raiding strategy” meant to keep Washington off balance by making it play defense around the globe.

There is also a Chinese challenge. Beijing is building influence for the long term by inserting itself into Latin American economies, infrastructure and communications networks. Through its Digital Silk Road strategy, China is proliferating surveillance technology that bolsters illiberal governments. Its larger Belt and Road Initiative features investments in nuclear power plants, space stations and other significant projects. Under its Global Security Initiative, Beijing is expanding internal security and intelligence programs in the region, as well.

There’s also a military component to Chinese policy, one that has, so far, remained somewhat disguised. From Cuba to Argentina, Beijing has been seeking — and sometimes acquiring — access to “dual-use” facilities with potential military uses. US officials reportedly worry that these facilities, such as the Amachuma Ground Station in Bolivia, could enhance China’s global military surveillance network, or eventually lay the basis for power projection in the Western Hemisphere.

Today’s autocracies aren’t recolonizing Latin America or supporting communist insurgencies. But the strategic implications of their behavior are real.

In the 20th century, Eurasian powers stirred the pot of political instability and anti-Americanism in Latin America in hopes of putting Washington on the defensive in its own backyard. Present-day US rivals know that playbook well.

America’s regional immunity underpins its global influence: A US fending off enemies in its own region will struggle to confront them in Eastern Europe or the Western Pacific. And if Russia or, more likely, China someday dominates its own region, it will have greater leeway to reach into the Western Hemisphere. If anything, the premium on preserving US sway may be higher today than it was in the past, given that pervasive Chinese economic influence in Latin America could spoil plans to nearshore critical supply chains.

The core of the Monroe Doctrine is as important as ever; another epoch of competition foretells another struggle for influence in the region to America’s south.

That’s not to say US officials should start waxing nostalgic about James Monroe and John Quincy Adams. There’s no profit in rhetoric that reminds even generally sympathetic Latin American observers of the region’s sometimes-humiliating experience with US power. The best way of obtaining a negative objective — denying America’s rivals strategic advantage in the Western Hemisphere — is through a positive program of regional cooperation.

The US will fare best at countering Chinese economic influence if it pursues a deeper regionalization of trade, manufacturing and financial relationships in the Western Hemisphere. If Washington wishes to turn countries away from Chinese digital and physical infrastructure deals that entrench debt, repression and corruption, it must find ways — whether alone or with democratic allies — of financing less-corrosive alternatives.

Alerting Latin American populations to the downsides of engagement with Moscow or Beijing requires helping governments and private citizens shine greater light on the role of Russian disinformation or China’s tightening grip on some of the region’s most vital resources. Investments in democratic institutions and civil society are good value amid political backsliding; so are efforts to rebuild long-atrophied relationships with the region’s militaries.

Containing hostile states, in the region and beyond it, entails consolidating relationships with friendly ones. The tighter the bonds of integration within the Americas, the better positioned the US will be within a fragmenting world.

That’s admittedly a tall order right now. Rather than sensibly discussing strategic challenges in Latin America, Republican presidential candidates are fantasizing about fighting the drug war by bombing Mexico. Neither major US political party has the courage to promote trade deals that might meaningfully increase economic integration with Latin America. Generating resources for the region has been a challenge for decades.

The problem, alas, goes well beyond Washington: From Mexico to South America, many once-reliable partners have been replaced by leaders who view the US with ambivalence at best. But the effort is worth making, because the more America struggles to secure its hemispheric position through positive policies, the more it may eventually rely on harder-edged measures instead.

Would the US really be more tolerant of its adversaries establishing military bases in Latin America today than it was during the Cold War? If it seems unthinkable that Washington might engage in covert meddling against an authoritarian strongman inviting America’s enemies into the region, or try to sway the outcome of a pivotal election in a pivotal state, that’s only because a generation of easy post-Cold War primacy left the US less reliant than it once was on such distasteful remedies.

As the longer history of US involvement in Latin America reminds us, even relatively respectable democracies will — when their strategic vitals are sufficiently threatened — do some dirty things.

Two centuries ago, the Monroe Doctrine asserted that the US must keep its rivals at bay within its own hemisphere. In the present era of rivalry, America will need to pursue the same policy, by one means or another.

Authored by Hal Brands, op-ed via Bloomberg.com,

The Monroe Doctrine is disparaged in Washington and Latin America, but it remains the foundation of the liberal international order the US leads today…

“I believe strictly in the Monroe Doctrine, in our Constitution and in the laws of God,” one American religious leader declared in 1923. That same year, 10 million American schoolchildren were subjected to a centennial recitation of President James Monroe’s famous doctrine in class.

“The American continents, by the free and independent condition which they have assumed and maintain, are henceforth not to be considered as subjects for future colonization by any European powers,” Monroe said in December 1823. For generations thereafter, that statement was a cardinal principle of US policy. It fused America’s founding ethos of anti-imperialism to the fierce nationalism and outrageous ambition that ultimately allowed the country to surpass every empire on Earth. It even became central to the America’s understanding of itself.

There have been no such celebrations this weekend to mark the 200th birthday. Most Latin American observers consider the Monroe Doctrine an imperial imposition. Even US officials now see it as an embarrassing anachronism. “The era of the Monroe Doctrine is over,” said Secretary of State John Kerry in 2013. Yet two centuries after it was issued, that policy remains more relevant than many might like to admit.

The Monroe Doctrine is a reminder that America’s strategic interests have always been intertwined with its revolutionary values. It represents the regional foundation of the liberal international order the US leads today. And although American policymakers often say the Monroe Doctrine is dead, they don’t — or shouldn’t — really mean it.

The Western Hemisphere was once an imperial battleground. At the start of the 1820s, Spain’s empire stretched from California to the Tierra del Fuego. Britain had territories and interests from Canada to Chile. France was clinging to imperial fragments around the Caribbean; Portugal was trying, vainly, to keep Brazil. Russia’s holdings included Alaska and outposts farther south. Powerful empires sought advantage in the Americas — and tried to keep a subversive republican newcomer well contained.

In 1823, America’s strategic landscape was menacing. The collapse of Spanish and Portuguese empires in Latin America was birthing new nations. But a coalition of European monarchies — the Holy Alliance of Austria, Prussia and Russia — was considering intervention to recolonize those countries; just two years earlier Russia had threatened a push down North America’s Pacific Coast. The Western Hemisphere was potentially facing a two-pronged absolutist assault. The US would then be surrounded by hostile, antidemocratic empires, foreclosing its future expansion and perhaps threatening its survival.

Monroe’s answer, drafted by Secretary of State John Quincy Adams, combined self-assertion with self-denial. Monroe warned European powers not to seek new colonies in the Western Hemisphere (implicitly counting on Britain, which also opposed its rivals’ expansion, to enforce that ban), pledging that America, in return, would steer clear of Old World conflicts. After a slow start, Washington ultimately honored the first part of the doctrine more faithfully than the second.

By the mid-19th century, the US had foreclosed European expansion in North America by taking much of the continent itself. Washington then began pushing European powers out of its neighborhood, forcibly evicting Spain from the Caribbean in 1898. During the early 20th century, the US intervened in unstable nations from Nicaragua to Haiti, primarily to deprive prowling Europeans of chances to meddle. Over the subsequent decades, Washington beat back challenges from countries — Imperial Germany, Nazi Germany and the Soviet Union — that sought Latin American footholds amid the epic global clashes that defined the age.

No other country in the modern era has dominated its surrounding region so thoroughly, and for so long, as the US. In this sense, America denied imperial prerogatives to its rivals, only to claim them for itself. But it is ironic that the doctrine is now considered a historical relic — because it continues to influence the long arc of US statecraft around the globe.

First, the Monroe Doctrine asserted an enduring principle of US strategy — that America requires a balance of power that favors liberalism. “It is impossible,” Monroe declared, “that the allied powers should extend their political system” — monarchy — to the Western Hemisphere “without endangering our peace and happiness.”

This wasn’t some rhetorical flourish. America’s founding struggle had been a revolt against monarchy. Its republican government cast it, immediately, into sharp ideological conflict against Europe’s absolutist regimes. So Monroe was simply explaining that the US could not flourish in an environment ruled by regimes that were inherently, even existentially, hostile to its liberal experiment. Nearly a century later, President Woodrow Wilson argued more or less the same thing in calling on his country to make a “world safe for democracy” in World War I.

The Monroe Doctrine also enshrined a related American tradition — hostility to rival spheres of interest. The modern era has seen the astounding growth of a US sphere of interest that began in North America and now reaches around the globe. Yet American leaders have never been as comfortable with other powers, especially autocratic powers, carving out their own domains.

Such arrangements, Monroe said, could be established only by coercion: Free peoples would never accept them “of their own accord.” Autocratic empires, whether in the Americas or elsewhere, would serve as platforms for subversion, intimidation and aggression against the world beyond. Since the early 20th century, America has fought hot wars and cold wars to keep Eurasian autocracies from establishing globe-threatening spheres of interest in their own regions — an extension of Monroe’s doctrine, but one he and Adams would have understood.

Finally, the Monroe Doctrine established the regional primacy that underpins America’s global power. If the US faced serious threats close to home, it would have to deploy vast armies to defend its long land borders. But if America faced no major threats within the Western Hemisphere, it would be free, eventually, to roam the world. Which means that the quasi-imperialistic Monroe Doctrine was vital to the liberal order the US eventually built.

A country plagued by nearby challenges could not have intervened three times, in the two world wars and the Cold War, to prevent autocratic powers from dominating Eurasia. It could not have secured overseas regions through globe-spanning alliances after 1945. It could not have anchored a thriving international economy and helped democracy spread more broadly than ever before.

America’s enemies understood this: Imperial Germany, Nazi Germany, and the Soviet Union all meddled in the Western Hemisphere because they knew that keeping the US preoccupied was essential to imposing their own, darker visions on the world.

The Monroe Doctrine cast its share of darkness, of course. The tools of US primacy included military interventions in Central America and the Caribbean; coups, covert action and aid for ugly counterinsurgencies in countries throughout the region; and land grabs in strategic points like Puerto Rico and the Panama Canal Zone. Hegemony is a messy business. No country can dominate a vast region while keeping its hands entirely clean.

When other powers pursued regional empires, in fact, they invoked US policy as their guide. Japan portrayed its aggression in China in the 1930s as a sort of Asian Monroe Doctrine. Today, when Chinese expansionists advocate “Asia for Asians,” or call Central Asia “China’s Latin America,” they are making, explicitly or implicitly, a similar claim. The truth is a bit more complicated.

Whatever its failings, the Monroe Doctrine did — with tacit support from the British Royal Navy — gradually curtail formal European colonialism in Latin America, an achievement of real value to the independent countries of the region. In the 20th century, moreover, a hemisphere free of US imperialism might well have been more susceptible to fascist or communist influence.

True, during the Cold War especially, the US protected its regional position through cooperation with friendly dictators. But preventing countries from going communist at least preserved the possibility they would later evolve toward democracy — as many eventually did, once their economies matured and the politics stabilized, in the 1970s and 1980s. The US placed itself firmly behind this democratic movement: Which of America’s great-power rivals would have done that?

American primacy has had other benefits. The fact that Latin America — a region suffused, sadly, with internal violence — has seen so little interstate conflict in the past century might, perhaps, testify to the role of US power in enforcing a hegemonic peace. Not least, insofar as Latin America has benefitted from the larger liberal order — one in which trade has surged, living standards have increased and global wars have been avoided for the last 80 years — it has also benefitted from the US regional supremacy that has enabled a degree of global progress.

Whatever the costs and benefits, the Monroe Doctrine long ago came to look like an imperial remnant in a post-imperial age. US officials mostly stopped publicly invoking the doctrine after a regionally polarizing CIA intervention in Guatemala in 1954. When Secretary of State Rex Tillerson mentioned the doctrine favorably in 2018, his comments were mostly treated as a costly gaffe. A policy Americans had once venerated now seemed painfully out of date.

True, after the Cold War, it had certainly seemed unnecessary. With US power unchallenged, with markets and democracy sweeping the region, everything was going Washington’s way. That’s no longer the case.

For years, the region’s politics have been deteriorating.

In Venezuela, Nicaragua and other countries, illiberal populists have set about destroying democratic norms and institutions. Democracy is fragile and political instability is rising across much of the region.

Peru is on its fourth president in the last three years; Argentina has elected a Donald Trump acolyte who promises to take a chainsaw to the political system. Mexico, which not long ago was moving toward stronger democracy and better ties with Washington, has regressed in both dimensions under Andrés Manuel López Obrador. Economic challenges often exacerbate political problems: Covid battered societies that were already suffering from high levels of economic insecurity.

Meanwhile, the US — which, since the 1990s, has seen the region primarily through the lens of illegal drugs and immigration — has been bleeding influence. And given that every great-power rivalry of the modern era has ensnared the Western Hemisphere, the bill for that strategic neglect is coming due.

One US antagonist, Russia, is forging anti-American alliances by making common cause with the region’s most thuggish leaders. When, in 2019, there was talk of US intervention in Venezuela to end the humanitarian catastrophe of Nicolas Maduro’s repressive rule, Russian military contractors raced to the country to protect his regime.

Russian weapons and intelligence support have bolstered another anti-American dictator, Nicaragua’s Daniel Ortega. Russian sniper rifles were used to kill pro-democracy protestors in 2018; Moscow and Managua have pursued cyber-cooperation to surveil and suppress Nicaragua’s opposition. Russian propaganda and disinformation fuel anti-US sentiment in Latin America and around the globe.

Russia’s presence in Latin America remains modest in comparison to the Cold War. But it is supporting states that brutalize their people and oppose US influence as part of a larger “raiding strategy” meant to keep Washington off balance by making it play defense around the globe.

There is also a Chinese challenge. Beijing is building influence for the long term by inserting itself into Latin American economies, infrastructure and communications networks. Through its Digital Silk Road strategy, China is proliferating surveillance technology that bolsters illiberal governments. Its larger Belt and Road Initiative features investments in nuclear power plants, space stations and other significant projects. Under its Global Security Initiative, Beijing is expanding internal security and intelligence programs in the region, as well.

There’s also a military component to Chinese policy, one that has, so far, remained somewhat disguised. From Cuba to Argentina, Beijing has been seeking — and sometimes acquiring — access to “dual-use” facilities with potential military uses. US officials reportedly worry that these facilities, such as the Amachuma Ground Station in Bolivia, could enhance China’s global military surveillance network, or eventually lay the basis for power projection in the Western Hemisphere.

Today’s autocracies aren’t recolonizing Latin America or supporting communist insurgencies. But the strategic implications of their behavior are real.

In the 20th century, Eurasian powers stirred the pot of political instability and anti-Americanism in Latin America in hopes of putting Washington on the defensive in its own backyard. Present-day US rivals know that playbook well.

America’s regional immunity underpins its global influence: A US fending off enemies in its own region will struggle to confront them in Eastern Europe or the Western Pacific. And if Russia or, more likely, China someday dominates its own region, it will have greater leeway to reach into the Western Hemisphere. If anything, the premium on preserving US sway may be higher today than it was in the past, given that pervasive Chinese economic influence in Latin America could spoil plans to nearshore critical supply chains.

The core of the Monroe Doctrine is as important as ever; another epoch of competition foretells another struggle for influence in the region to America’s south.

That’s not to say US officials should start waxing nostalgic about James Monroe and John Quincy Adams. There’s no profit in rhetoric that reminds even generally sympathetic Latin American observers of the region’s sometimes-humiliating experience with US power. The best way of obtaining a negative objective — denying America’s rivals strategic advantage in the Western Hemisphere — is through a positive program of regional cooperation.

The US will fare best at countering Chinese economic influence if it pursues a deeper regionalization of trade, manufacturing and financial relationships in the Western Hemisphere. If Washington wishes to turn countries away from Chinese digital and physical infrastructure deals that entrench debt, repression and corruption, it must find ways — whether alone or with democratic allies — of financing less-corrosive alternatives.

Alerting Latin American populations to the downsides of engagement with Moscow or Beijing requires helping governments and private citizens shine greater light on the role of Russian disinformation or China’s tightening grip on some of the region’s most vital resources. Investments in democratic institutions and civil society are good value amid political backsliding; so are efforts to rebuild long-atrophied relationships with the region’s militaries.

Containing hostile states, in the region and beyond it, entails consolidating relationships with friendly ones. The tighter the bonds of integration within the Americas, the better positioned the US will be within a fragmenting world.

That’s admittedly a tall order right now. Rather than sensibly discussing strategic challenges in Latin America, Republican presidential candidates are fantasizing about fighting the drug war by bombing Mexico. Neither major US political party has the courage to promote trade deals that might meaningfully increase economic integration with Latin America. Generating resources for the region has been a challenge for decades.

The problem, alas, goes well beyond Washington: From Mexico to South America, many once-reliable partners have been replaced by leaders who view the US with ambivalence at best. But the effort is worth making, because the more America struggles to secure its hemispheric position through positive policies, the more it may eventually rely on harder-edged measures instead.

Would the US really be more tolerant of its adversaries establishing military bases in Latin America today than it was during the Cold War? If it seems unthinkable that Washington might engage in covert meddling against an authoritarian strongman inviting America’s enemies into the region, or try to sway the outcome of a pivotal election in a pivotal state, that’s only because a generation of easy post-Cold War primacy left the US less reliant than it once was on such distasteful remedies.

As the longer history of US involvement in Latin America reminds us, even relatively respectable democracies will — when their strategic vitals are sufficiently threatened — do some dirty things.

Two centuries ago, the Monroe Doctrine asserted that the US must keep its rivals at bay within its own hemisphere. In the present era of rivalry, America will need to pursue the same policy, by one means or another.

Loading…