–>

July 2, 2022

Back in 2001, when the Oscars were still somewhat bearable, I remember being elated that the movie Gladiator won so many awards. Other than the fact that it was a great movie, there was something spitefully delicious in witnessing a victory that the elitist class clearly felt was unworthy but, their manicured hand forced by box office reality, was grudgingly obliged to recognize in order to save face.

‘); googletag.cmd.push(function () { googletag.display(‘div-gpt-ad-1609268089992-0’); }); }

Why didn’t the elites like Gladiator? Because it pitted a materialistic, power-hungry totalitarian attempting to dissolve senatorial checks on his authority against a commoner-turned-warrior who lives, fights, and dies for such quaint notions of family, country, and the gods. Sound familiar? I suspect the Hollywood types actually enjoyed the movie until the closing scenes when they realized, flabbergasted, that Emperor Commodus was understood to be the bad guy.

Gladiator also presented an image of the masculine ideal that is utterly at odds with everything Hollywood stands for. At the time, the Academy was lecturing us rubes that thoroughly unwatchable dreck such as The Talented Mr. Ripley is the standard towards which to strive. It is a classical example of projection. Like Mr. Ripley, leftists are timid, scared, equivocating, deceitful, vengeful, and sexually confused, and they think you should be too.

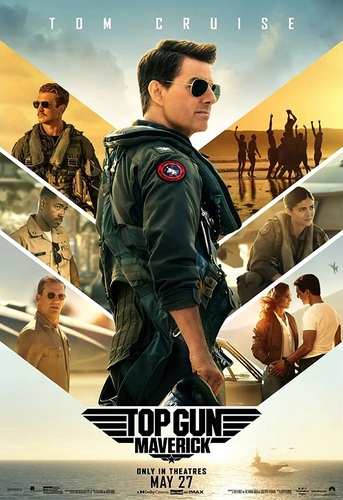

Fast forward to today, and we find that Top Gun: Maverick is loved by the masses and hated by the elites for many of the same reasons.

‘); googletag.cmd.push(function () { googletag.display(‘div-gpt-ad-1609270365559-0’); }); }

There are many themes in Top Gun: Maverick to which the humanity in us responds. The first is laid out almost immediately, when the Navy’s fighter squadrons find themselves in danger of being budget-cut out of existence in favor of their drone-savvy counterparts. The justifications of Rear Admiral Cain (Ed Harris) for drone warfare fall almost exactly in line with justifications for socialism (i.e., the implementation of a rational, calculated, mathematically-failsafe system which excludes both the error of human judgment, the need for human thought, and the chimera of human meaning). The stubborn refusal of Maverick (Tom Cruise) to prioritize drones over pilots (bureaucratic automation over free will) calls from us the essence that recognizes that we are still better than the machines we create.

The entire movie is generously interspersed with human beings, both men and women, not only mastering the machines they create (be they motorcycles, ships, or fighter jets), but also using them to master the environment around them to new and dangerous limits. It is a constant testament to the human spirit which builds skyscrapers, walks on the moon, and, yes, wins wars. Our heroes approach the edge of the unknown and then step into it. Whatever virtues the movie characters lack, courage isn’t one of them, and there is something in that which most of us admire and some of us resent.

The plot involves a secret mission to destroy a uranium-enrichment plant in an enemy country (understood by 99.99% of the audience to be Iran but assumed by luminaries like Tomris Laffly to be Russia, despite the fact that Russia has had nukes since Stalin’s reign and has no need to secretly enrich uranium).

Therein lies the best part of the movie, which is the underlying truism: We are the good guys. Pure and simple. None of the characters needed to say it. There were no soaring speeches. There were no moral dialectics interwoven with the script, or even any examples of, for lack of a better phrase, the bad guys behaving badly. Most refreshingly, there was no moral equivalence between the West and its genocidal enemies, as there was in Saving Private Ryan and Munich (both, not coincidentally, creations of Spielberg Inc.) or in the otherwise brilliant The Killing Fields.

Therein lies the best part of the movie, which is the underlying truism: We are the good guys. Pure and simple. None of the characters needed to say it. There were no soaring speeches. There were no moral dialectics interwoven with the script, or even any examples of, for lack of a better phrase, the bad guys behaving badly. Most refreshingly, there was no moral equivalence between the West and its genocidal enemies, as there was in Saving Private Ryan and Munich (both, not coincidentally, creations of Spielberg Inc.) or in the otherwise brilliant The Killing Fields.

Rather, Top Gun: Maverick returns to the clarity of Clint Eastwood’s American Sniper and Ridley Scott’s Black Hawk Down, both of which made evident for anyone with a moral compass as to on which sides reside the good and evil of the respective contextual conflicts. We are the good guys. They are the bad guys. And if you need the fictional characters to dumb it down for you as to why, then you’re watching the wrong movie, you attended the wrong school, and you were reared by the wrong parents.

The cast of pilots has grown from the original film (all white men and one black man) into something more diverse, yet with a natural, non-political feel to it. The cast reflects the military as it is today, with whites, blacks, Latinos, Asians, both men and birthing people women, in the cockpits. But this is done organically, without any of the mawkish “Back when my granddaddy served” speeches reminding the audience that there were no fighter jets in Washington’s time but, if there were, you can bet your white privilege that minorities and women would not have been allowed to fly them.

‘); googletag.cmd.push(function () { googletag.display(‘div-gpt-ad-1609268078422-0’); }); } if (publir_show_ads) { document.write(“

Oh, and Penny Benjamin (Jennifer Connelly) drives not a Prius, but a 1973 Porsche 911 S. Think of the carbon footprint…

You can see why critics hated it. Tomris Laffly called it “brouhaha jingoism and proud fist-shaking.” Richard Trenholm of CNET dismissed it as “military fetishism” and compared our military pilots as children who “delight in playing with high-speed toys which just happen to be built for killing people.” Richard Brody of The New Yorker claims (in between bizarre rants against both Reagan and Trump) that Cruise succeeds “solely by giving in to his emotions, by expressly not controlling them.” There’s that leftist projection again.

And so the yawning chasm between the American consumer and the “movie critic” eunuchs grows ever wider. As of this past weekend, Top Gun: Maverick surpassed the $1 billion mark worldwide and over $525 million in North America. Meanwhile, 2021 and 2022 saw the Oscars’ lowest watched ratings in history. To date, Top Gun: Maverick has already earned more than the last seven Best Picture winners combined.

Maybe Americans don’t go to the theater to be lectured. Maybe they tire of paying money to be guilt-tripped about their culture, their history, and their very existence. Maybe people who actually produce, protect, and work, utilizing their marketable and sought-after skills, grow weary of the sanctimony from those whose “job” it is to watch movies all day long. Maybe after years of their cities being torched, their statues being toppled, their border being invaded, their churches being desecrated, their life savings being inflationed away, their military being indoctrinated, their opinions being criminalized, and their children being groomed in public schools, they’re in the mood for some affirmation that they aren’t the planet-infesting cancer they’re so often portrayed as.

If you haven’t seen the movie yet, go see it. It is unashamedly pro-American, and without having to spell it out. It is a microcosm of the American ideal, one full of cockiness and unforced errors, but one which stumbles its way toward the light and toward victory. The movie reflects the confidence of our young, the wisdom of our old, and the utilization of both to push a little farther out west. Ignore the cowards hiding in the forgotten columns of their dying publications. Go see the movie, and be proud of the expanse of human achievement.

Image: Paramount Pictures

<!– if(page_width_onload <= 479) { document.write("

“); googletag.cmd.push(function() { googletag.display(‘div-gpt-ad-1345489840937-4’); }); } –> If you experience technical problems, please write to [email protected]

FOLLOW US ON

<!–

–>

<!– _qoptions={ qacct:”p-9bKF-NgTuSFM6″ }; ![]() –> <!—-> <!– var addthis_share = { email_template: “new_template” } –>

–> <!—-> <!– var addthis_share = { email_template: “new_template” } –>