Because documentary films contend with real people and real events, it is to be expected that they shape the public’s understanding of those people and events. But it is a different matter altogether when those films start to have a tangible impact on the people or events they are purporting to document.

What if Fahrenheit 9/11 had somehow brought about an end to the Iraq War? Or if Grey Gardens had led to Big Edie and Little Edie renovating their dilapidated estate? In such hypothetical cases, would the filmmakers be considered bystanders to the consequences of their films or, for good or ill, participants in those aftereffects?

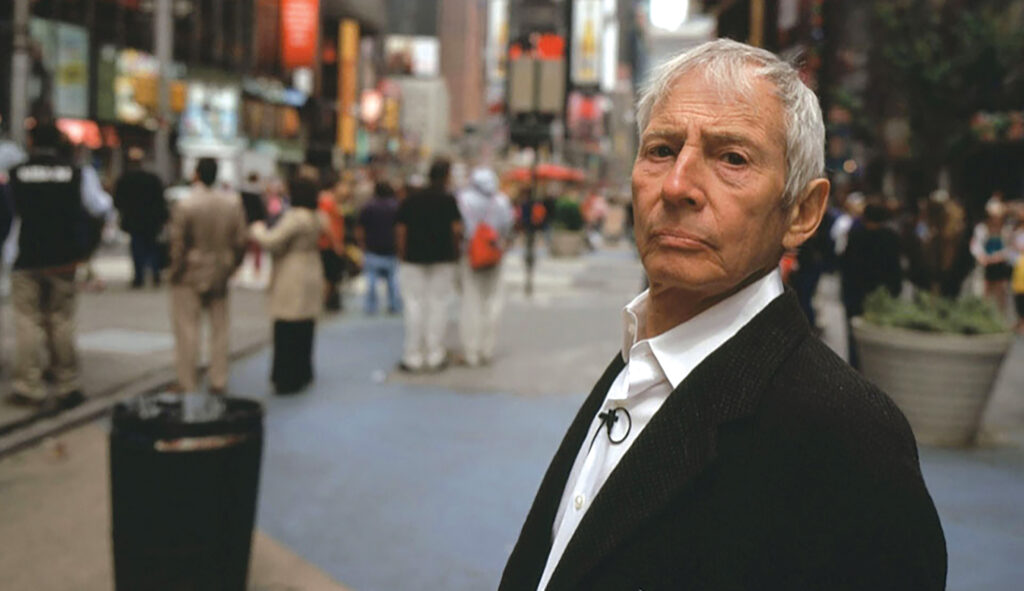

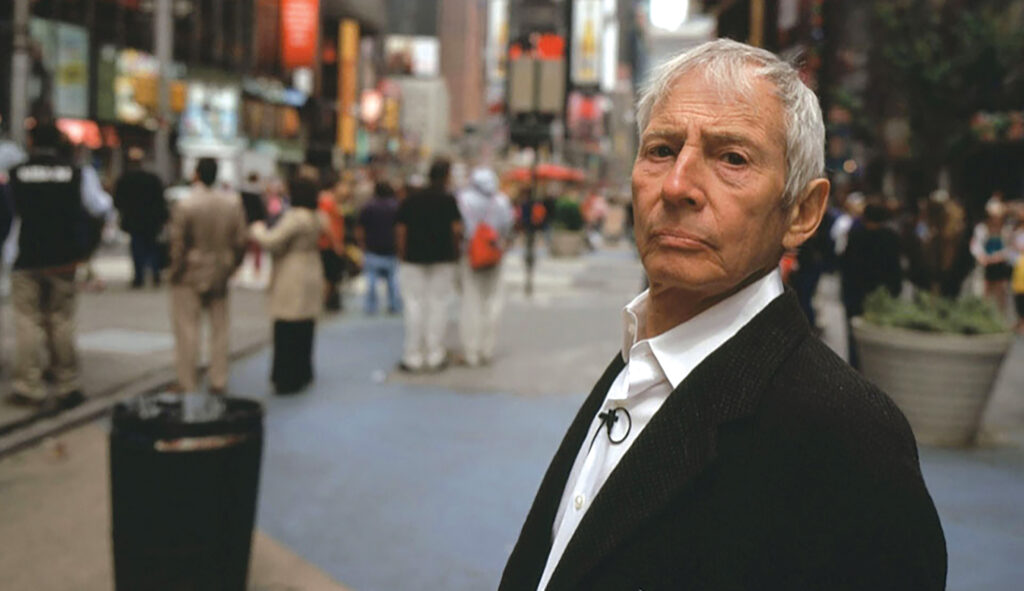

Such are the questions and quandaries that must be pondered in watching Andrew Jarecki’s long-belated documentary miniseries The Jinx: Part Two. Like its predecessor, the new series revolves around Robert Durst, the vastly wealthy and exceedingly eccentric heir of a New York real estate family. To have known the psychopathic, indeed homicidal Durst seems to have placed one at risk of losing one’s life: In 1982, Durst’s first wife, Kathie, disappeared, an incident in which he has long been considered culpable. In 2000, his friend Susan Berman was killed, a crime for which he was charged and convicted. And in 2001, a neighbor, Morris Black, was killed, a crime to which he admitted but of which he was, unbelievably, acquitted. The six episodes in the new series air weekly through May 26 on HBO, which made the first four episodes available to the press.

The original The Jinx sketched this history in all of its grimness and oddness, except for one key element: At the time the first series began airing in February 2015, Durst had not been charged in the death of Berman, but the documentary proved so damning that it ultimately led its subject to justice. In the final episode, Durst, who had, of his own volition, agreed to be interviewed for the series, made the fatal error of grousing to himself, off camera but on microphone, something about having “killed them all, of course.” In March, armed with a latex facial mask, a map of Cuba, and, as ever, loads of cash, Durst was apparently planning to relocate permanently to the island nation when he was arrested by the authorities — who, it turns out, had already been in touch with the filmmakers for some time. The first episode of the new series offers the following title card: “In 2013, The Jinx filmmakers shared the evidence they had discovered with law enforcement. As a result, the LAPD renewed their investigation into the murder of Bob’s friend Susan Berman.” Oh.

In 2021, Durst was convicted and sentenced to life in prison for murdering Berman. Later that same year, he was charged with murdering his first wife, Kathie, but he died at 78 in January 2022.

Talk about Peak TV! This is the show that helped put a man behind bars. “I think he would be free today if he had just kept his trap shut,” New York Times reporter Charles Bagli said. The first series and its impact are peppered through this new series: There’s footage of a kind of “watch party” at which investigators, witnesses, and Kathie Durst’s family members gathered around to watch the infamous “killed them all” episode back in 2015. And at one point during Durst’s trial for killing Berman, hypotheses related to the case are traced to an earlier feature film Jarecki made about Robert and Kathie Durst, the fictionalized All Good Things. Even so, The Jinx: Part Two does not linger on the knotty ethical issue of the series’s own role in Durst’s downfall.

Instead, the show hurtles headlong into relitigating Durst’s alleged and actual crimes and documenting his long-deferred prosecution for one of them, the murder of Berman. Among the most compelling segments are numerous jailhouse phone calls and conversations between the chipper, persuasive, demanding Durst and his surprisingly wide network of rich and strange friends. Foremost among them is Durst’s second wife and chief keeper of secrets, Debrah, with whom he talks, at one point, about selling several of his properties to help make cash available for what is sure to be a costly defense. (You know you have entered a strange social sphere when real estate valuations in the Hamptons are discussed in a jail meeting room.) As heard on these jailhouse communiques, Durst’s weirdly catty commentary on the unfolding trial and its participants is undeniably entertaining.

Those newly interviewed include the judge in the case, several jurors, various attorneys, and, most intriguingly, many from Durst’s orbit, some of whom come across as bizarre as one might imagine. Among Durst’s oddest longtime bosom buddies is one Nick Chavin, a former foul-mouthed country singer who performed under the name “Chinga Chavin” and who later, with Durst’s support, entered the business world. He professes his love and loyalty to his friend but has enough of a conscience to cooperate with the authorities eventually. “What do you do when your best friend kills your other best friend?” Chavin asks plaintively, referring to Durst’s murder of Berman.

That even sometimes credible-seeming people manage to get caught up in aiding, abetting, or merely providing moral support to Durst is a testament to the way in which proximity to great wealth can wreak havoc on both common decency and common sense. In recounting the investigation, Jarecki is aided immensely by Los Angeles Deputy District Attorney John Lewin, an unusually affable but utterly committed cold-case prosecutor: He’s loquacious, tenacious, and tireless in pursuing what he has judged to be the truth.

In all of the measurable ways, both iterations of The Jinx represent true-crime television at its finest. The shows are slick and sleek, effortlessly sliding in relevant pieces of information, countless cliffhangers, and even a few open questions. Reenactments of certain events are tasteful and restrained. The casting call for the show must have sought those belonging to the unusual category of “actors who look like Robert Durst in soft focus.”

CLICK HERE TO READ MORE FROM THE WASHINGTON EXAMINER

Yet the blurring of the line between the filmmakers’ inquiries into the Durst saga and their involvement in its resolution hangs over the show. Of course, that line has been smudged many times, often under fairly tawdry circumstances: The infamous ITV special Living with Michael Jackson precipitated the criminal case against its subject, and the equally infamous unaired Fox special with O.J. Simpson, If I Did It, provided confirmation, for any remaining naysayers, of Simpson’s guilt in the murder of his ex-wife and her friend. Both projects were undertaken with the initially enthusiastic participation of their ostensible subjects — as was the original The Jinx. While far fancier in its presentation and sense of self-importance, The Jinx is somewhat depressingly cut from the same cloth. Is this documentary storytelling or entrapment, or (more likely) some bizarre hybrid of both only possible in a media environment in which notorious figures, such as Simpson and Durst, can’t help but speak to a curious public?

By raising these points, I do not mean to dampen interest in a compelling entry in the annals of American crime nor diminish the significance of a deranged killer being held to account. The fact remains that The Jinx: Part Two wraps up only part of the story. Another filmmaker, one who knew neither Durst nor his chroniclers, ought to take up the topic of what happens when documentary filmmaking and the legal system collide.

Peter Tonguette is a contributing writer to the Washington Examiner magazine.