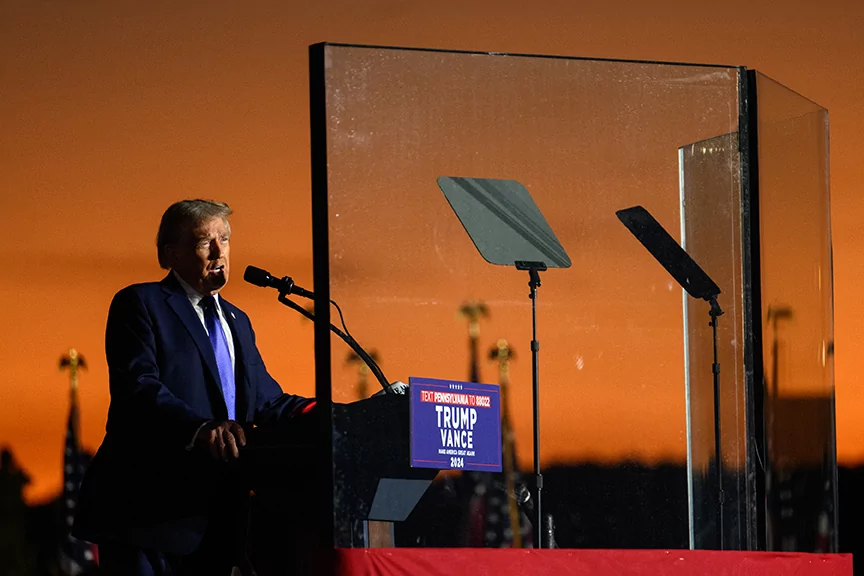

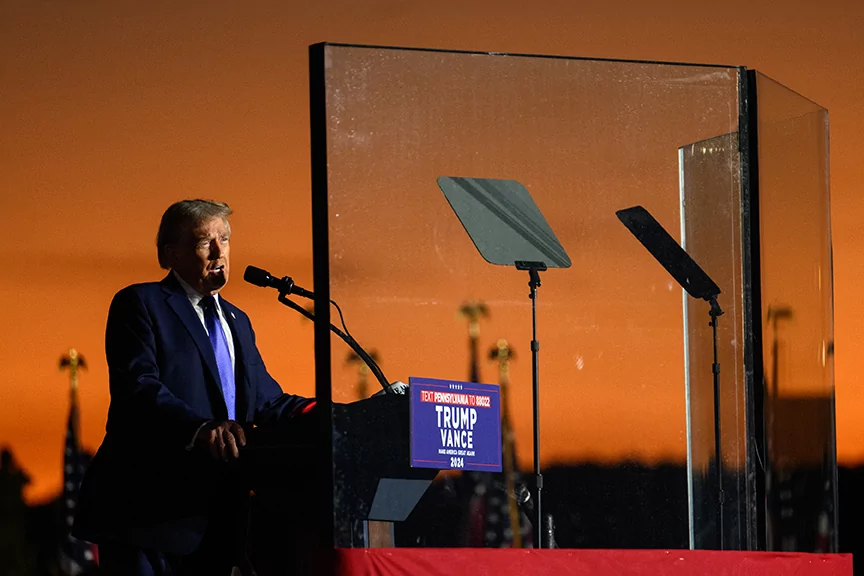

LATROBE, Pennsylvania — “If we win Pennsylvania, we win the whole damn thing.”

Two weeks ago, former President Donald Trump announced these words to rallygoers in this Westmoreland County town at a packed event, which included several former Pittsburgh Steelers taking the stage to endorse him and steelworkers as well, who even got the former president to put on a hard hat that ruffled his hair.

It was a statement that made the thousands of supporters, most of which were young, go understandably wild with emotion. Many of the attendees I spoke to were young women, many of them mothers with their children, who could not wait to vote in the first election they were truly excited about.

Trump wasn’t wrong. Heading into the final stretch of the election, I’d rather be him than Vice President Kamala Harris in the Keystone State. Several pollsters across the political spectrum shared data showing that Trump has a consistent edge in Pennsylvania and that Harris is at a standstill.

However, he’s a better fit for the commonwealth than Harris for reasons beyond just polling. In weeklong travels across the 67 counties in Pennsylvania, all the indicators told a story outside the worldview, or bubble, of Washington, D.C., and New York City, of why Harris has failed in key places to earn people’s votes and Trump has found a way to bring out new voters and earn just enough support to win the state.

In 2016, David Urban, a western Pennsylvania native, West Point graduate, and former chief of staff to the late Arlen Specter, a Republican senator who changed his party to Democrat in 2010 but lost in the Democratic primary, was a senior adviser to Trump.

Urban, who did not work with Specter when he changed parties, understood the importance of the smaller counties outside of Pittsburgh and Philadelphia, explaining that there was an untapped center-right constituency in those counties that could sway the election for Trump over Hillary Clinton.

Urban said most people thought he was nuts, except, of course, Trump, who had found appeal with traditionally unmotivated voters because he was not part of the system of either party. It worked. Trump over-performed in the smaller counties and, to the astonishment of both Democrats and Republicans, flipped the traditional Democratic counties of Luzerne, Erie, and Northampton in significant amounts. He thus won the state that had not favored a Republican for president since 1988.

“Those counties negated whatever happened in Philly and Pittsburgh,” said Urban, adding, “Going in, I understood Trump needed 2,000 voters over Romney’s numbers in 2012 in ten counties, less so in the more rural ones, and he would win the state narrowly.”

The same holds true for today. In 2020, President Joe Biden was able to cut into those margins with the working class in those small counties, in part because of his years of referring to himself as “Scranton Joe” and the familiarity he earned campaigning for downballot Democrats in local races, and also in part because of the circumstances of COVID-19. Now, though, Biden’s policies as president and his comportment are turning those voters off.

Voters in places just 15 minutes outside Pittsburgh and Philadelphia will tell you, more often than not, they do not have a voice in D.C. and are acutely aware of how people there, and in New York, view them as “lesser than” or “backward.”

Former President Barack Obama reinforced this at a San Francisco fundraiser when he said Pennsylvanians who “get bitter, they cling to guns or religion or antipathy toward people who aren’t like them.” Clinton reinforced it with her “basket of deplorables” and “irredeemable” remarks when she was running, and Biden himself reminded voters a week before the election, with a slip of the tongue, that he views them as “garbage.”

Trump took Biden’s remark and rolled with it, dressing in an orange vest and riding in a garbage truck in Wisconsin. His ability to be nimble with the situation has earned him more votes than it cost him. The number of parents I saw either in person or posting on social media from Pennsylvania dressed in garbage bags, orange vests, or as Mcdonald’s employees, a hat tip to Trump’s decision to work at the fast-food chain two weeks ago, showed an undercurrent that has been missed.

“It may surprise some people in the Democratic Party that folks don’t particularly like to be called fascists, or Nazis, or have their family members called that,” said Brad Todd, a Republican strategist, and co-author of The Great Revolt: Inside the Populist Coalition Reshaping American Politics.

Todd said it may turn out that the voters who determine Pennsylvania’s outcomes will more than likely be people who work with their hands, such as “a barber or a welder or a waitress.”

Karen, Angela, and Elizabeth are all working-class waitresses. One owns the small Main Street Diner in Westmoreland County, and the other two are servers. All three, just eight years ago, would have been Democrats, but today, they are all in for Trump.

“It is the economy,” said Angela, who was busy bussing tables. Elizabeth, who just turned 18 in August, has worked at the diner since she was 14 and at the bar down the street as a server. She is also drawn to Trump.

“It is all on the economy and the way he addresses voters from places like here,” she said.

Gallup pollsters have shown, in survey after survey, that the economy remains voters’ number one concern, and they don’t like the direction the country is going in. Conversely, Harris’s biggest struggle has been connecting with voters, such as Angela and Elizabeth, on the economy.

She has also struggled to connect with voters on energy concerns in Pennsylvania, where the industry is a giant. Switching from “I would ban fracking on day one” in a hypothetical to “I won’t ban fracking” falls flat because her own administration has placed a ban on exporting liquid natural gas for the foreseeable future, and she has not only done nothing about it, she has not even mentioned it.

Her events in the state have also often been very staged, with attendees coming from an invitation-only list, while her speeches have rarely tapped into the vein of the economic hurt people are feeling. In recent weeks, her comments have fallen into a darker narrative that has not inspired persuadable people.

Her messages on abortion, “greedflation,” and “snackflation” have also fallen flat. Almost everyone in Pennsylvania knows abortion in the state is legal for up to 24 weeks, and the only person who can take abortion away is the sitting governor. However, Gov. Josh Shapiro (D-PA) has repeatedly said he would not do that. Meanwhile, nobody thinks the increase in the cost of snacks was caused by Trump.

His rallies have worked, despite ridicule and skepticism from reporters, because he showed up in places such as Butler, Luzerne, Cambria, Erie, and Northampton, where people feel unseen and unheard and where climate change and pronouns mean less than the cost of food.

In interviews across the state, middle-class voters, white, black, and Hispanic, are now voting shoulder to shoulder, not divided by race but by the economic despair they are experiencing together. Food costs, gas prices, utilities, car insurance, rent, and mortgages (if they can even afford to buy a house) are driving their vote.

These voters often did not attend college, but they are middle-class and have found their calling as artisans, such as hairdressers, medical technicians, welders, plumbers, waitresses, laborers, or small business owners.

Todd said those voters are the key: “There’s a real chance Trump will end up with less from college-educated women than he did in 2016 for sure, he is likely to make up for it with lower income, lower education Democrats, people who used to be Democrats and are not anymore.”

He also said, “Gen Z is not turning out to be as liberal as Millennials. And we were all assured that demography was destiny. And turns out that when you’re coming of age with a pretty crappy economy, you’re not real happy about it.”

There is also still a silent suburban mother cohort, which includes married and unmarried female voters with children in the home, in places such as Allegheny, Erie, Bucks, and Northampton counties who preferred to keep their names out of the story.

Harris will win with women without children, specifically unmarried women without children, a bloc she’ll win by about 70 points, said Todd.

“When we talk about a gender gap, what we really are talking about is a marriage gap and a parent gap, and that’s something that’s culturally changing in politics,” he said.

The one thing that confused people as to why this cycle is leaning toward Trump in Pennsylvania is just two years ago, Shapiro and Sen. John Fetterman (D-PA) won statewide. This made some reporters believe that Pennsylvania had gone back to being a blue state. What they missed is both Shapiro and Fetterman ran as centrist, “get-things-done” Democrats and stayed away from the left-wing cultural matters that drive moderate Democrats and Republicans away.

“People have also missed how rightward the state has moved,” said Todd, referring to the stunning voter registration movement for Republicans in the state that has the Democrats with the weakest voter registration dominance in the state in decades.

In 2008, Obama won the state by a landslide. He ran on “hope and change” and being part of something bigger than self, and it worked. In 2012, he ran on internationalism, division, and social justice, and as a result, 280,000 fewer Pennsylvanians voted for him. While Obama still won (more narrowly), the parties were shifting. Clinton ran the same divisive race in 2016, and most of the media was shocked by her loss. She calculated that she could win with Obama’s numbers in Philadelphia and Pittsburgh. She did win those, but she lost in the rest of the state.

CLICK HERE TO READ MORE FROM THE WASHINGTON EXAMINER

Biden was able to pick those voters back from Trump, but Harris has struggled to connect with them, and it appears just enough of Trump’s suburban voters are coming back to him to join the middle-class coalition to power his comeback.

Now, there may be a surge of voters who do not account for supporting Harris. Still, based on the two candidates’ messages, delivery, and understanding of what people are looking for, both pollsters and voters said they’d rather be Trump than Harris on Tuesday.