Donald Trump was one of the most famous people in the world when he descended the escalator at Trump Tower in 2015. Since then, he has been in a constant state of campaigning, winning elections, governing, campaigning, losing elections, and campaigning again.

The lines between his conduct as a private citizen and his efforts to obtain, retain, or regain office have often blurred together. Those lines have seemingly grown even fuzzier for the former president, who has been indicted on several counts, and found guilty on dozens of others, for actions he took either before he was campaigning or while he was the president but may have been acting as a private citizen.

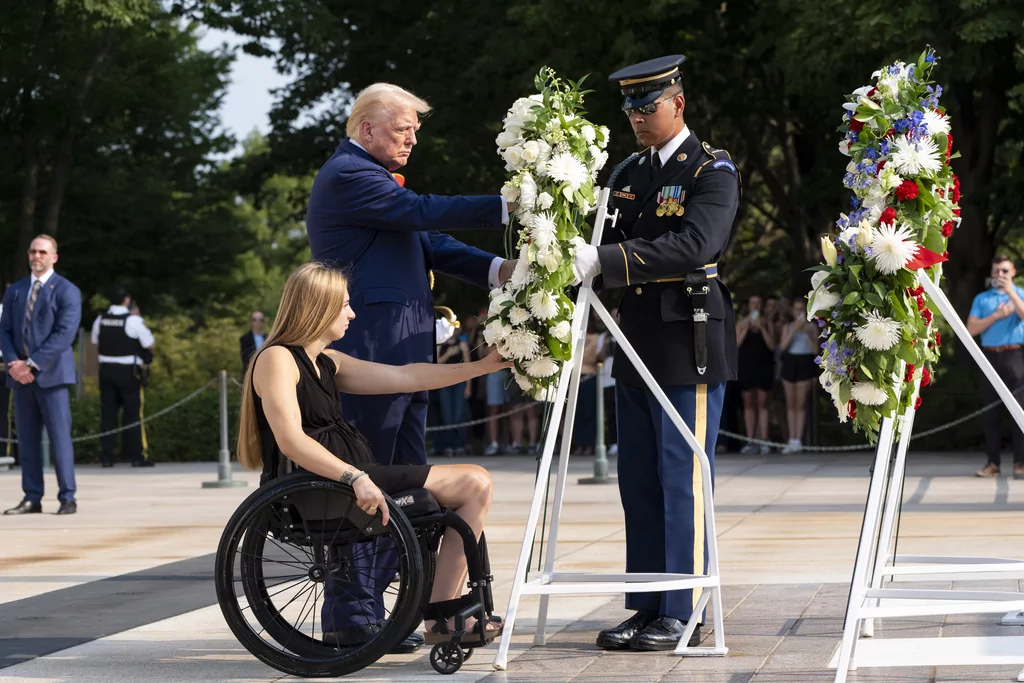

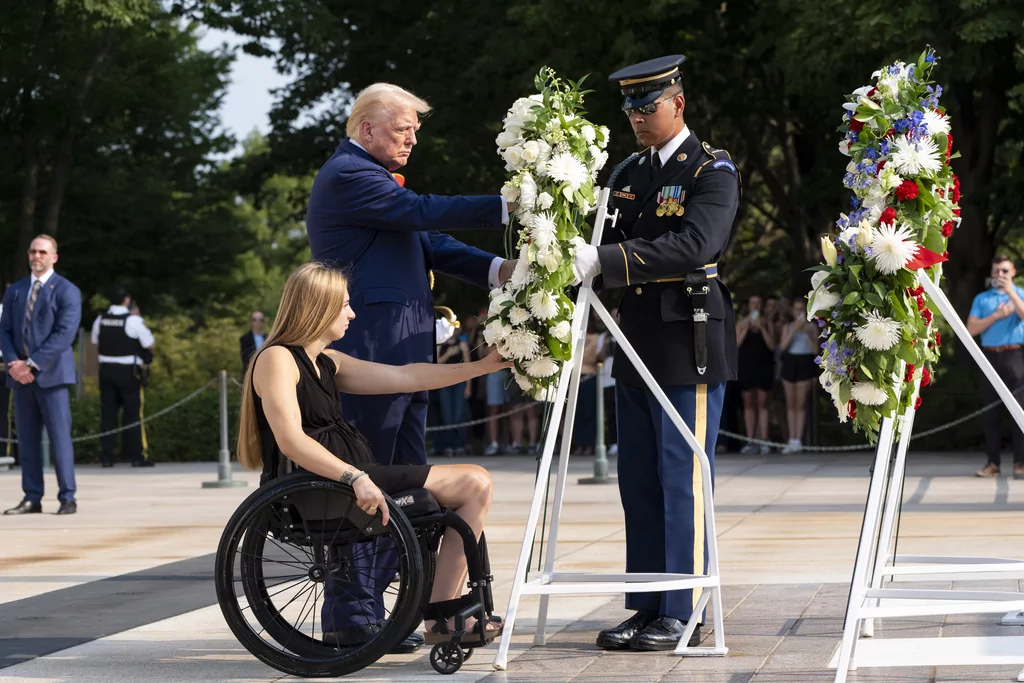

Last month, his campaign appeared to run afoul of the rules at Arlington National Cemetery when photographers accompanied him and a pair of Gold Star families to visit the grave site of soldiers who were killed in the Abbey Gate bombing as the United States stumbled out of Afghanistan.

Trump may be an extreme case, such was his celebrity before his foray into politics. But it raises the question of whether candidates can ever truly step away from the campaign trail to act as private citizens or whether they are locked in the public eye until Election Day.

Privacy rights

An ironclad right to privacy for political candidates cannot be found in black and white in the Constitution. The Fourth Amendment protects individuals against unreasonable searches and seizures but says nothing about the treatment of politicians.

There is general agreement that citizens have the right to be left alone. However, candidates for public office largely waive those rights as the price of admission to run for office.

For example, we learn far more about most presidents’ medical and financial records than other individuals. Both Trump and President Joe Biden have been criticized for not sharing as much with the public as their predecessors had.

Trump’s tax returns were stolen and leaked by a former contractor and were the subject of a special investigation by the New York Times.

Biden was driven out of the 2024 presidential race when rumors of his inability to hold up under the rigors of being the president were laid bare on the debate stage with Trump. Vice President Kamala Harris and the rest of the president’s inner circle have since had to explain what they knew about Biden’s health, when they knew it, and why they had done nothing to tell the public about his deterioration.

The comparison is imperfect. Most people would argue voters have a right to know whether the commander in chief is physically able to perform his role. But presidential candidates are also expected to share information about their health, and when they don’t, they come under fire.

Recently, both Trump and Harris were called out for not releasing comprehensive medical records with only a matter of weeks left before voters go to the polls — and days until they can begin mailing in ballots.

While there were consequences for the thief who stole Trump’s tax returns and Biden paid politically for concealing his ailing health, most voters were not bothered by learning more about the two men than they would have been willing to share themselves.

Arlington National Cemetery furor

The primary problem Trump and his campaign ran into at Arlington National Cemetery last month was not that he was campaigning while on the grounds, which is illegal, but rather that his staffers allegedly got into an altercation with an employee.

Trump’s team denied there was any altercation, though spokesman Steven Cheung did tell the Washington Examiner that someone “clearly suffering from a mental health episode” tried to block members of the team.

“There was no physical altercation as described and we are prepared to release footage if such defamatory claims are made,” Cheung said in a statement at the time. “The fact is that a private photographer was permitted on the premises and for whatever reason an unnamed individual, clearly suffering from a mental health episode, decided to physically block members of President Trump’s team during a very solemn ceremony.”

The Army backed the employee, saying in a statement that she was “abruptly pushed” and it was “unfortunate that the ANC employee and her professionalism has been unfairly attacked.”

In between scuffles about whether and what kind of altercation took place at the cemetery, Trump came under fire for bringing photographers and videographers with him to the ceremony. Overt political activity at Arlington National Cemetery is illegal, but it is not clear Trump was participating in “partisan political activities” that are banned on the grounds.

Trump was invited to the graves by Gold Star families and posted pictures of himself with the families on social media. He later released an ad with footage of him laying a wreath at the Tomb of the Unknown Soldier.

The altercation took place after the wreath ceremony, which was also recorded and broadcast by news networks.

Katie Charkasky, a former federal prosecutor, told the Washington Examiner that the question of whether Trump broke any rules by showing up as an invited guest who happens to be running for president is a complicated one precisely because he is a candidate.

“The courts have acknowledged that the First Amendment has its ‘fullest and most urgent applications to speech uttered during a campaign for political office,’” Charkasky said. “So, limitations on campaigning on certain government property and things of that [nature], along those lines, it’s not a clear-cut line.”

Not all legal experts agree about how questionable the lines are, particularly considering the rules at, and special status for, Arlington National Cemetery.

Tanya D. Marsh, a professor of law at Wake Forest University, explained in a post on Military.com that because cemeteries are allowed to create their own rules, for everything from who can be interred in them to what kind of activities are allowed there, an invitation from families or someone acting as a private citizen would not provide cover for using the appearance for “partisan political activity” later.

“In general, the public may take photos at Arlington, as may the media, with prior authorization and an escort,” Marsh wrote. “As of at least April 2022, however, no one may film in the cemetery for ‘partisan, political or fundraising purposes’ – which is precisely what Trump appears to have done.”

Gag order

Criticism for his conduct at Arlington National Cemetery is not the first time Trump’s duality as a private citizen and presidential candidate has posed problems.

Throughout the trial in New York, in which a jury found him guilty of 34 counts of fraud relating to payments he made to porn star Stormy Daniels to keep silent about an alleged affair, Trump lashed out at the judge and prosecutors. As a result of his statements outside the courtroom and attacks posted online, Judge Juan Merchan placed a gag order on the former president, preventing him from speaking about several aspects of the case against him.

Initially told he was not allowed to talk about witnesses, jurors, potential jurors, prosecutors, or family members of prosecutors or the judge, Trump complained that he was being treated unfairly and was being targeted because of his status as the presumptive Republican presidential nominee.

Trump trashed the gag order as “unconstitutional” and pointed to it as a major impediment to conducting a successful campaign. While Biden, at the time the presumptive Democratic nominee, and Democrats were free to use Trump’s time in the Manhattan courtroom in speeches, posts, and ads, the former president was limited in what he could discuss.

Legal scholars were not all convinced that Merchan had broken any rules with his gag order, though they did say it was a rare move and one that might have lent credence to Trump’s complaints he was being targeted specifically because he was a candidate.

“It just goes into the narrative that he’s being persecuted,” Donald Nieman, a Binghamton University professor who specializes in teachings on U.S. legal history, told the Washington Examiner in May. “And then he transforms that into [a message] that because he represents the everyday American, they’re being persecuted too because the person they really want to be president is being denied a fair chance to run his campaign.”

Charkasky was adamant that Trump’s First Amendment rights were heightened, and infringed, by the gag order because he was in the middle of a campaign.

“Courts … are very cautious about protecting the First Amendment interests, especially of candidates for public office, and especially for candidates for the presidency, in particular,” Charkasky said. “So that’s part of why that gag order — I guess it’s still in place at this point — is more offensive than if it was just a regular defendant, and even then, it probably wouldn’t have withstood scrutiny for most people.”

Human moments

Throughout the campaign, Trump has showed moments of vulnerability and has appeared to let down his guard as a politician. The moments often came in politically advantageous circumstances — talking about seeing his brother struggle with addiction or his granddaughter speaking about him during the Republican National Convention in July.

When he went on comedian Theo Von’s podcast last month, a move that is part of a strategy of attracting young, online, male voters, Trump shared why he does not drink or smoke.

“I had a great brother who taught me a great lesson — don’t drink,” Trump said. “Don’t drink and he said don’t smoke. He smoked and he drank. And he was a great guy. … And he had a problem with alcohol.”

In July, Republicans in Milwaukee and anyone tuning in to watch the RNC as it unfolded were given a glimpse at how Trump might appear to his family when he is not on stage or on the trail.

“The media makes my grandpa seem like a different person,” Kai Madison Trump, the former president’s eldest granddaughter told RNC attendees on the third night. “But I know him for who he is. He’s very caring, loving. And he truly wants the best for this country.”

Both moments came during overtly political events — an interview and a convention where he was being nominated to be the GOP presidential candidate. But they also further blurred the lines about how Trump the individual might be viewed as opposed to the bombastic candidate.

Advice from the trail

Trump and other candidates are likely frustrated by what feels like a double standard afflicting them for choosing to run for office. As ostensible public servants, why are they subjected to harsher treatment and suffer greater consequences for inadvertent missteps or even regular conduct off the campaign trail?

Wendy Davis, a two-time Democratic congressional candidate in Utah, told the Washington Examiner that heightened scrutiny comes with the territory.

“When citizens enter a county clerk’s or state office to file their candidacy, they officially enter the political arena,” Davis wrote in an email to the Washington Examiner. “Typically, the candidate is sworn in by an election official. During this process, they raise their right hand and affirm their eligibility to run for the specified office, verify their residency, and agree to adhere to election laws. From that moment, the candidate is held accountable to the jurisdiction’s election regulations and may face serious consequences for non-compliance, including possible removal from the ballot.”

The overlap between being a candidate and a private citizen is complicated, Davis said. Despite her and others’ best efforts to draw dividing lines between when they are actively campaigning and when they are turned off, their “political role becomes an inseparable part of their identity.”

Their identities are more concrete when they are in public, she said.

“When a current elected [official] is in a public space and engaging in activities that are unique to their office, they are acting in an official capacity and not as a private citizen,” she wrote.

Trump is not a current elected official, though he is running as a quasi-incumbent and has received the media attention of a current official given his prominent role in the Republican Party.

CLICK HERE TO READ MORE FROM THE WASHINGTON EXAMINER

In Davis’s view, candidates and officials have no space to operate as anything other than someone who is exposed to the public’s eye — for better or worse.

“Politicians relinquish the luxury of being ‘private citizens’ when they choose to become ‘public servants,’” she said. “When politicians violate laws, norms, or unwritten rules, the media and voters take notice. The real question becomes how voters will respond to such transgressions within the complex calculus they use when making their ballot decisions.”