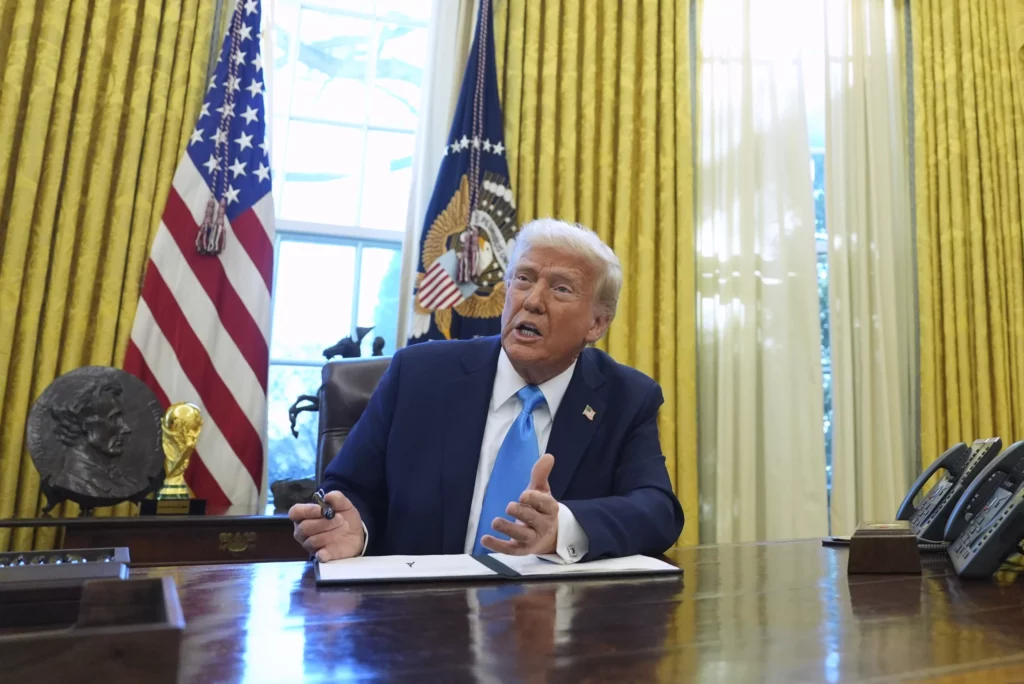

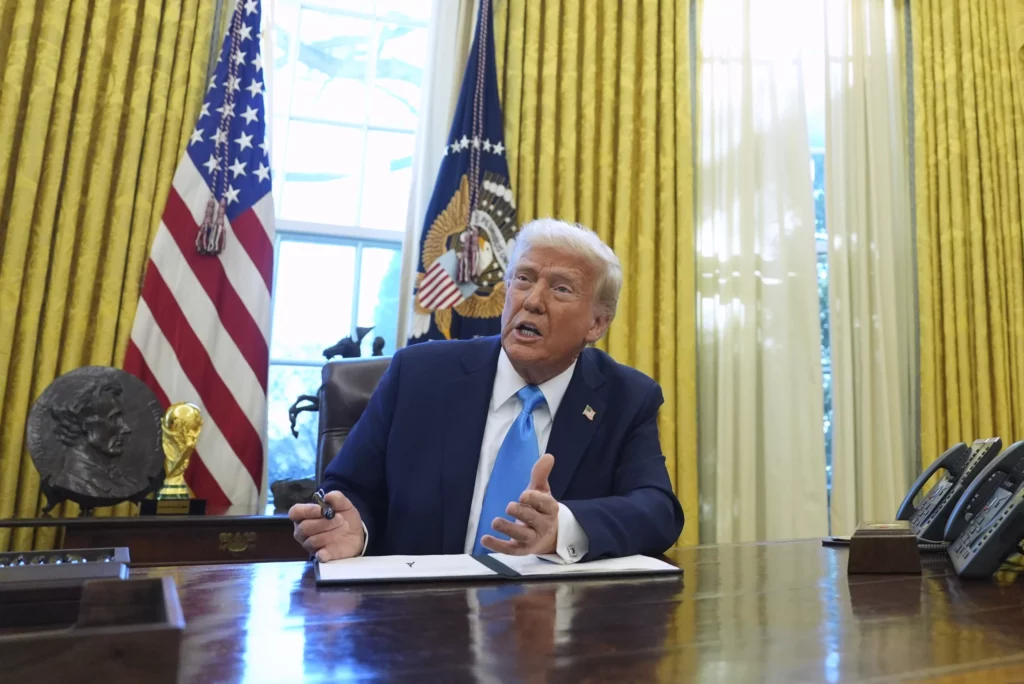

President Donald Trump‘s executive crusade to punish three countries he deems responsible for the deadly fentanyl epidemic has raised questions on whether tariffs, especially on Canada, will solve the U.S. drug problem.

In the Feb. 1 executive order, Trump identified Canada, China, and Mexico as playing significant roles in the U.S. fentanyl epidemic that has killed a record-high number of people annually. In turn, Trump imposed double-digit tariffs against each nation until the amount of fentanyl being seized at the nation’s border drops to next to nothing.

China has, for years, produced the ingredients used to mix the final fentanyl product, while Mexico has been where drug cartels make the drug and move it over the southern border into the United States. Profits are then laundered back to Mexico through China.

But Canada’s inclusion in the executive order and tariff imposition has put border and drug experts at odds over how appropriate the action was, particularly given the unaddressed demand side of the epidemic.

What did Trump’s executive order state?

Trump first imposed tariffs on three countries on the basis that fentanyl represented a major health and public safety threat. He’s since expanded and altered the tariffs plans several times, giving the stock markets whiplash and causing recession fears.

“The extraordinary threat posed by illegal aliens and drugs, including deadly fentanyl, constitutes a national emergency under the International Emergency Economic Powers Act (IEEPA),” his Feb. 1 executive order stated.

Until the crisis is “alleviated,” Canada and Mexico would face 25% tariffs on imports from the U.S., while China faces a 10% tariff. Canada’s energy resources would only be taxed 10% instead of 25%.

The executive order stated that Canada contained a “growing” presence of Mexican cartels that operate fentanyl and nitazene synthesis labs. It also cited an unspecified study that found fentanyl was increasingly being produced in Canada and exported globally.

Trump’s signing the executive order followed through on his promise last November to impose a 25% tariff on products from Canada and Mexico “until such time as Drugs, in particular Fentanyl, and all Illegal Aliens stop this invasion of our Country.”

However, data from the government agency tracking fentanyl seizures paints a different picture of how prevalent drug smuggling is in Canada.

Where is fentanyl coming from?

Fentanyl intercepted coming into the U.S. is seized by U.S. Customs and Border Protection. The federal agency’s officers at sea, land, and air ports of entry make seizures, as well as Border Patrol agents who work between the land ports of entry on the Canadian and Mexican borders.

In the most recent fiscal year, 2024, CBP personnel stopped 21,900 pounds of fentanyl from getting into the country, according to CBP data publicly available online. The year ran from November 2023 through October 2024.

That haul contained enough fentanyl to kill more than 4 billion people. While CBP’s seizure was significant, it is not able to stop all fentanyl that smugglers attempt to get into the country, according to the White House.

Of the 21,900 pounds, roughly 21,100 pounds were intercepted at the southern border. Just 43 pounds of the 21,900 pounds were caught at the Canadian border.

So far in the first four months of fiscal 2025, a tiny amount of fentanyl has been thwarted at the northern border, staying on trend with last year’s results. Of 5,600 pounds of fentanyl intercepted in that period, only 10 pounds were caught along the northern border with Canada.

The Department of Homeland Security website states that on a national level, roughly 90% of interdicted fentanyl is nabbed at the ports of entry as opposed to between land ports of entry.

Will tariffs solve the fentanyl epidemic?

Trump had teased last November plans to impose tariffs on U.S. neighbors. In a proactive move, Canada began cracking down on fentanyl and synthetic opioids well before Trump imposed tariffs this year.

In a Dec. 9, 2024, through Jan. 18 “national sprint,” Canadian police arrested more than 500 people and seized 101 pounds of fentanyl and 15,000 pills of fentanyl and other opioids, according to a statement from the Royal Canadian Mounted Police on Feb. 26.

Simon Hankinson, senior research fellow in the Border Security and Immigration Center at the conservative Heritage Foundation think tank in Washington, said there is a growing problem in Canada that does need to be addressed.

“I have spoken to Canadian officials recently a few times and they seem to think they are making progress. But there are a lot of labs making drugs, and more ready-made fentanyl coming into Canada and being consumed locally or shipped south to us via trucks,” Hankinson wrote in an email. “The scope of the drug problem in Canada is hard for me to measure, but they do have one.”

But even a crackdown on Canada’s part may not fix the problem, according to Dr. David Herzberg, a historian of pharmaceuticals and professor in upstate New York.

“There is historical evidence that a particular illicit drug supply chain can be temporarily disrupted by ‘supply side’ approaches. However, if the demand side remains the same, then when supply goes down, prices will rise, increasing profits and drawing in new suppliers who build a new supply chain,” wrote Herzberg, director of the Drugs, Health, and Society Program at the University of Buffalo, in an email.

“All of this assumes that the illicit drug supply chain exists in the first place, which, in the case of Canada and the U.S., does not appear to be the case,” Herzberg, author of “White Market Drugs: Big Pharma and the Hidden History of Addiction in America.”

David J. Bier, director of immigration studies at the libertarian Cato Institute in Washington, agreed that the problem was the U.S. government’s to fix internally.

“Tariffs are taxes paid on legally imported goods and services, and they will not affect illicitly smuggled drugs in any meaningful way,” Bier wrote in an email. “Regardless, Canada is not a significant source of fentanyl to the United States, so assuming the tariffs are meant to motivate the Canadians to stop drug smuggling, they would have no effect whatsoever on US fentanyl problems.”

Some skeptical of Trump’s true intentions

Some critics have claimed that Trump is citing his national security authorities as a way to get out of the U.S.-Mexico-Canada Trade Agreement, which he negotiated during his first term due to frustrations that Canada and Mexico came out on top of the 2020 trade negotiations.

The trade deficit with Canada and Mexico has surged since the deal was reached, with Canada’s ballooning from $26 billion to $63 billion since 2019 and Mexico’s growing from $99 billion to $172 billion over the same time frame.

Still, Trump has held for decades that deficits mean the U.S. is getting a raw deal from its trading partners, and a rising movement on the political right shares that view.

“Here it seems Trump is using a different US drug policy tradition: using fear of drugs to pursue entirely unrelated political goals,” Herzberg said.

Trump’s February executive order stated that fentanyl was responsible for killing 75,000 people in the U.S. a year and warranted a serious response.

TRUMP DHS DEBUTS PHONE APP FOR ILLEGAL IMMIGRANTS TO SELF-DEPORT

Commerce Secretary Howard Lutnick maintained on Sunday that the tariffs were “part of a drug war.”

“Canada and Mexico must shut down the flow of fentanyl across our border and China must stop subsidizing the production,” Lutnick wrote in a post to X. “The Trump Administration will not apologize for saving American lives.”

Haisten Willis contributed to this report.