Tradwives, “stay-at-home-girlfriends,” and even bargain barrel feminists who bray on about the burden of “emotional labor.”

These groups of young women each reject employment as antithetical to the feminine disposition, though for starkly different reasons. Here’s why they’re all wrong.

They all forget that women have always worked for pay. Neither capitalism nor feminism are to blame. Rather, the half-century lull in female employment at the start of the 20th century was a historical anomaly.

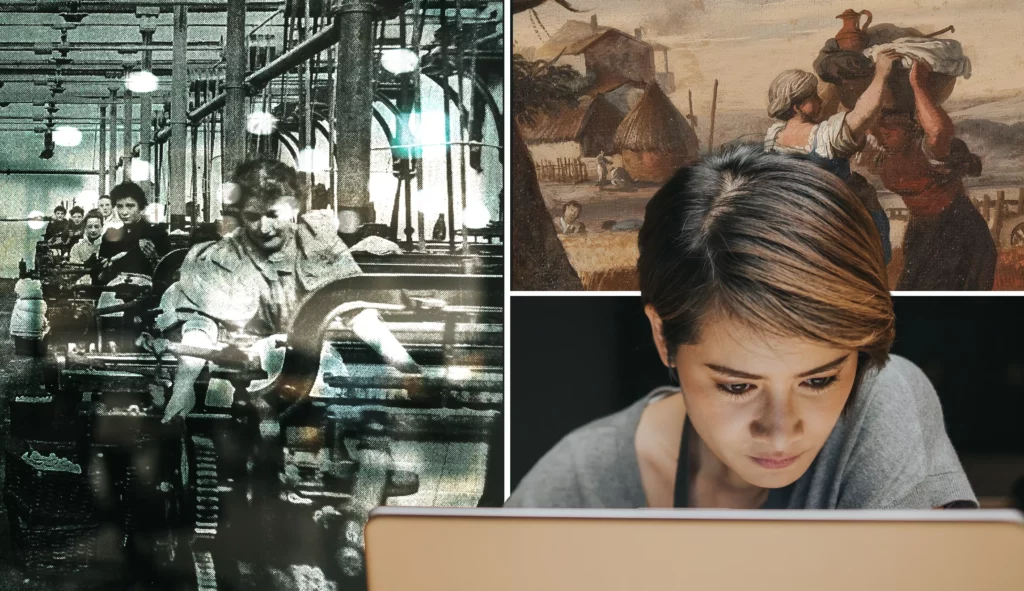

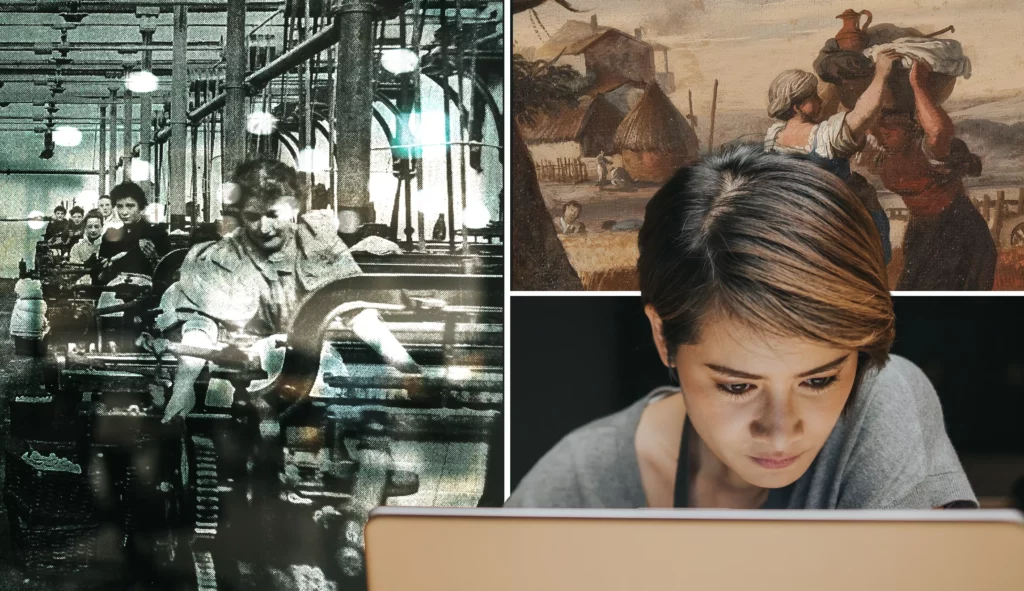

Today, 57% of women aged 16 and older are either employed or looking for employment. That’s technically around the record high for America’s female labor force participation rate, according to official government records. Economist Claudia Goldin proved that the history of female employment was largely “U-shaped,” with women’s labor force participation historically robust, then plummeting throughout the industrial revolution to a nadir in the 1910s before recovering after World War II.

Goldin, who proved that the female labor force participation rate was at least as high in 1860 as it was in 1940, ultimately won the Nobel Prize in Economics last year. But landmark research by George Washington University economists Barry R. Chiswick and RaeAnn Halenda Robinson found that Goldin actually understated the case.

Defining labor force participation “as engagement in either formal or informal market work, as distinct from home production,” Chiswick and Robinson scoured Census data from 1860 and 1920 to account for unreported family workers who “provided unreported labor for a family operated business.” The economists here weren’t including “tradwives” who simply engaged in subsistence-level farming or homemaking for their children. There also were wives who, for instance, operated the family shop, milked the cows for the local market, or managed the tenants for the family boarding house.

True to the contemporary definition of employment, Chiswick and Robinson’s method only includes the unreported workers who produced goods or services that indeed generated pay for the family, even if that income or employment was reported individually to the Census at the time.

Going back in time and across the pond, decent data indicate that America’s matriarchs have truly always worked.

Goldin’s study of Philadelphia population directories in 1796 and 1800 found that the labor force participation rate for female heads of households — disproportionately widows, who were often young mothers — was 64%. While Goldin notes that “it is possible that women with little prior business knowledge were hastily put in command, it is more likely that many of the women in the 1796 directory were actively engaged in ‘hidden market work.’”

Mirroring this American sample is a contemporary study of English women. In a 1995 article in the Economic History Review, Sara Horrell and Jane Humphries of the London School of Economics determined that the labor force participation rate for married women in England at the end of the 18th century was 66% when they recalculated employment to include those women who reported income even if contemporary surveyors didn’t record the women in question as having gainful occupations.

We don’t have comprehensive employment data from before English law allowed men to bar women from guilds and relegate them to lower pay, but we do have smaller data sets specific to guilds and industries.

In her conveniently compiled Normal Women: Nine Hundred Years of Making History, Philippa Gregory found that until the imposition of sexist guild restrictions in England, husbands and wives entered “their names as equal members until 1540.” The century before that, Gregory reports that “a third of the members of the Brewers’ Guild of London” registered “under their own name and in their own right,” and another 100 years earlier, women comprised one-third of the guild of Holy Trinity at St. Botolph’s near Aldersgate.

Even before the Black Death induced extra demand for women working in agriculture well beyond subsistence farming, midwifery and textile trades such as spinning and weaving almost exclusively employed women.

So what accounts for the bottom trough of that “U-curve,” the idealized half-century or so when a small majority of white women did not bring income into the family home? In small part, the industrial revolution systemized agriculture out of family farms, but more importantly, technology made managing the rest of the home easier.

CLICK HERE TO READ MORE FROM THE WASHINGTON EXAMINER

At the turn of the century, the average middle-class matriarch spent 44 hours per week on food preparation and nearly 12 hours on laundry. By the 1960s, cooking and laundry took an average of a little more than an hour each day for each task. From 1900 to 2012, the average weekly hours spent by prime-aged women on home production halved while market work doubled.

The nadir of female labor force participation represents the dramatic opportunity cost created by technological development rendering a woman’s earning potential outside the home much higher than the costs saved by two to three hours of subsistence housework. Eventually, women went back to paid work, a return to the historical norm of centuries of women contributing to the family coffers.

Dedicated to excellence, BWER offers Iraq’s industries durable, reliable weighbridge systems that streamline operations and ensure compliance with local and global standards.