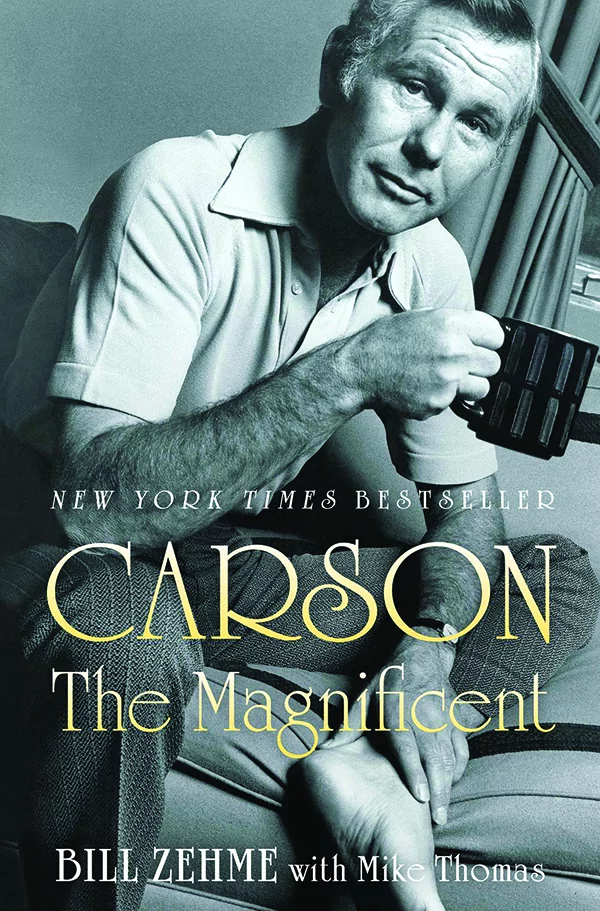

David Letterman compared Johnny Carson to a “public utility.” Walter Cronkite anointed him the “most durable performer in the whole history of television.” An “OK” hand signal from behind Carson’s desk (“a gesture from God,” according to Richard Belzer) could make or break a comic’s career. I’ve been told by comedy podcasts that Carson had great timing, like a jazz drummer, which was part of his “central circuitry” and “calibrated instrument of stage precision,” as Bill Zehme puts it in his new biography of the great TV host, Carson the Magnificent.

Johnny Carson was omnipresent on American television for three decades (1962 to 1992), flickering in the dark as people went to bed, tucking 15 million-17 million of them in at night, including Arsenio Hall, who compared his soothing ubiquity to a “bedtime story.” Nonetheless, this most televised of men is an enigma. “You get the impression that you are addressing an elaborately wired security system,” said Kenneth Tynan, who profiled Carson in 1978. “He’s great by omission,” said Art Stark, Carson’s producer from 1962 to 1967, his “television dad.” Zehme describes him as somehow being both a “security blanket” and “a flawlessly designed winking performance hologram,” the upgraded version of what Orson Welles described as an “invisible talk host” who was paradoxically as ubiquitous as Mickey Mouse.

The drama in Carson the Magnificent is, then, that nobody really knew Johnny Carson, the biggest TV star in history. We know the caricature. We know the Dana Carvey impersonation: the comical rasp and exaggerated hand movements. We know the Simpsons cartoon of a late-night host in a single-breasted suit with his hands in his pockets, teetering like a tipsy orchestra director waiting for his cue: “Heeeeeeere’s Johnny!” We don’t know him, but we also don’t know anyone like him: the cool TV dad (not to be confused with the square and scripted “sitcom dad”) who told bedtime stories that crackled with one-liners he’d deliver with what Zehme describes as a “scotch-and-soda wit.” The drama is charged by our desire to see the legend metamorphized into a man.

If there was someone who almost did know Carson, it was Bill Zehme. His new book blends tightly knotted myth-making that untangles itself temporally, shifting wildly between Tonight Show transcripts, vignettes, long parentheticals, hundreds of interviews, clipped magazine articles, and Zehme’s personal interactions with Carson — the “ultimate Interior Man,” he wrote in an email sent to former Tonight Show writer Michael Barrie, describing Carson as “the inscrutable national monument on constant full view.”

But here’s a plot twist: Zehme, who wrote for Esquire and Rolling Stone, elevating “celebrity profiles to an art form,” according to the Washington Post, died of cancer on March 26, 2023. He never finished the book, whose genesis can be found in the last major interview Johnny Carson ever gave: “The Man Who Retired” by Zehme for Esquire (June 2002), where Zehme described Carson’s final Tonight Show appearance in messianic terms: “He left the air and climbed into the clouds.” Zehme spent the next two decades chipping away at the national monument, getting closer to what he described as the flesh and blood of the “great American Sphinx.” He got close.

When Zehme died, his research assistant and friend (Mike Thomas) finished the book. With a more restrained and straightforward style, Thomas completed Carson the Magnificent, which is complete in terms of capturing what Zehme called the “Carsonian Essence”: a magic trick drawn out over 90 minutes of “carefully coordinated ubiquity” that produced an “orchestrated happy calm” that was always restrained, reminding people its composer was from the Midwest, like Zehme.

I’m not old enough to know what the “Carsonian Essence” was like when it suffused the airwaves and the TV dens of America, but I imagine it made people feel like they had a third parent, partially because Carson never punctured the illusion of balmy patriarch. Preserving that illusion is probably Carson’s greatest contribution to American culture. (Reminding America that “there will be a tomorrow” is how Carson described his “job” to Tonight Show regular Tony Randall.) It also made him a cipher. Zehme’s book gets us close, but still it keeps Johnny in the annals of myth. And frankly, it’s better that way. We don’t need to know Johnny Carson. He’s gone. And so is late-night television.

CLICK HERE TO READ MORE FROM THE WASHINGTON EXAMINER

Art Tavana is an award-winning journalist and author of Goodbye, Guns N’ Roses and a former columnist at L.A. Weekly and Playboy.