Born in Toronto in 1944, Lorne David Lipowitz, as Lorne Michaels was known at birth, was, like all baby boomers, seemingly predisposed to undermine, question, and, above all, parody the prevailing conventions of his civilization. “People start to be funny early in their lives, when they notice the difference between the official version and what their eyes and ears tell them,” said Michaels, who is described in Susan Morrison’s authoritative new biography as being an eager devotee of American television, especially The Phil Silvers Show. Fatherless at 14, Michaels welcomed the mentorship of Frank Shuster, part of a Canadian comedy team that had logged appearances on The Ed Sullivan Show and the father of Michaels’s future wife, Rosie. “Shuster explained how jokes worked,” Morrison writes.

The die was cast. Joined by pal Hart Pomerantz, and initially bearing his original name, Michaels performed as the comedy duo Lipowitz and Pomerantz. Later, the pair became the eponymous co-hosts of one of innumerable purported Saturday Night Live prototypes, The Hart and Lorne Terrific Hour on the CBC. The team found paying work as writers on The Beautiful Phyllis Diller Show and Laugh-In, and, in a solo capacity, Michaels worked on specials for Lily Tomlin and Perry Como. These were not awful credits, but for Michaels, they felt like simply a matter of marking time. Enter NBC executive Dick Ebersol, who, seeking original programming to supplant reruns of The Tonight Show on Saturday evenings, met with Michaels. “For the first time in my life, I knew who I was,” Michaels said. “I could’ve been persuasive, or possibly charming, at other times in my life, but this time, I was very clear on what I wanted to do.”

After much haranguing and convincing, the blank space on the schedule became Saturday Night Live, whose deceptively simple credo was enunciated by Michaels to his first squad of writers and performers: “Let’s make each other laugh, and if we do, we’ll put it on television and maybe other people will find it funny.” Neatly undercutting this assertion, Morrison assiduously documents the countless policies and procedures that governed Michaels’s reign at SNL, including his insistence on distinguishing between one-note “skits” and fully fleshed-out “sketches;” his directive to writers whose pitches were too complex, known as “premise overload;” and his instruction to make the set intimate and shambling rather than, in the manner of past TV variety shows, huge and sleek.

While so many movies and TV shows seem ruled by nameless executives, informed by self-defeating focus groups or test-marketing strategies, and produced amid an atmosphere of inoffensive caution, SNL has operated, for the great majority of its five decades on the air, as a vessel for the individual sensibility of its creator and producer. To be sure, SNL has experienced frequent, sometimes annual, changeover in many creative departments, from the writers’ room to the on-screen talent. Yet Michaels, who has overseen every season of the show but five in the 1980s, has imposed on SNL a unique constancy, a commitment to a certain brand of humor at once deeply goofy and believably true. This ethos unites such otherwise unrelated skits as Garrett Morris’s “News for the Hard of Hearing,” Mike Myers’s Wayne Campbell and Linda Richman, guest Sam Waterston’s commercial for robot insurance, and host Christopher Walken’s record producer who inexplicably insists on “more cowbell” — each created, written, and performed by someone other than Michaels, but nonetheless bearing his unmistakable, auteur-like imprint.

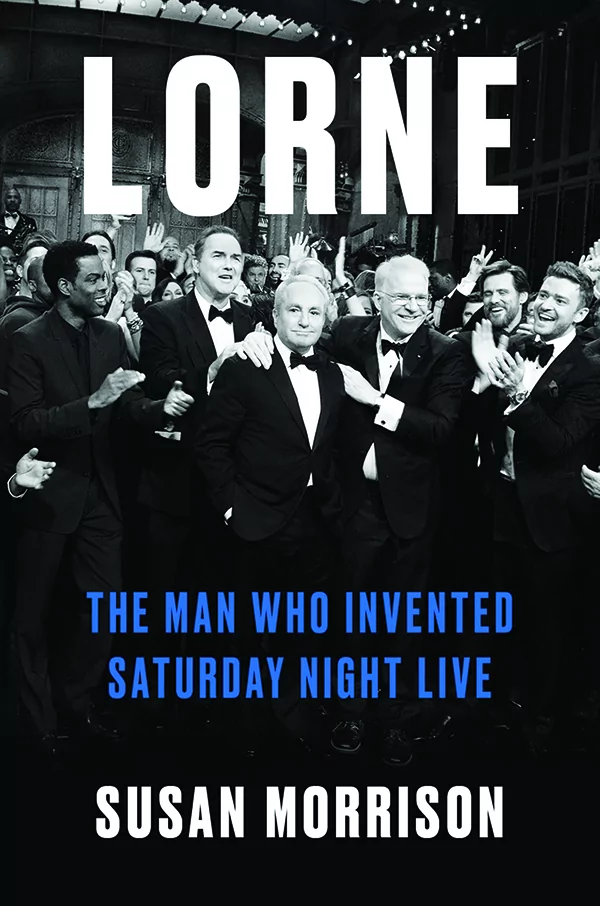

The 80-year-old sketch comedy mogul’s longevity is an invitation for biographers, and Morrison has obliged by producing a doorstop of a book that details its subject’s life and work with depth and insight. Although her book can suffer from a degree of inapposite self-seriousness, Morrison, by and large, succeeds in confirming Michaels’s significance and celebrating his endurance in the transient land of TV. “In Peter Pan, the boys never grow up,” Morrison writes. “At SNL, they are rotated out and replaced, with Michaels presiding in a role that’s part Wendy, part Captain Hook. He didn’t escape aging, but the company he’s kept has prevented him from becoming a dinosaur, or worse, an unhip dinosaur.”

Although the vintage years of SNL have been well and tiresomely documented, Morrison has the advantage of recounting them anew through a single pair of eyes. Thus we learn about Michaels’s salary terms, his interactions with network higher-ups of various eras, and his careful fitting together of the right mix of writers, performers, musicians, and guests innumerable times over the course of dozens of seasons. Many of the Michaels-adjacent stories will sound familiar — say, the accounts of Chevy Chase’s boastfulness and John Belushi’s wantonness — but Morrison tells them well.

Equally well managed are Michaels’s period of exile and homecoming: From 1980 to 1985, SNL was turned over to others, including, most notoriously, Woody Allen’s one-time best friend Jean Doumanian during the ill-fated 1980-81 season. Wooed back to salvage his creation, Michaels presided over some patchy seasons of his own — remember Anthony Michael Hall as one of the Not Ready for Prime Time Players? — before being delivered by ace talent on the order of Dana Carvey, Mike Myers, Phil Hartman, and Jan Hooks. There were still ups and downs to come, but, for Michaels, the ups outweighed the downs. Morrison writes of how easily Michaels acclimated himself to a lifestyle of the rich and famous, upgrading his wardrobe and “trading his sneakers and desert boots for loafers” by the fourth season, acquiring grand tastes, collecting grand friends, and making a small fortune through savvy business deals at his company, Broadway Video.

Yet a curious air of disappointment hovers over the last chapters of this exhaustive book. Michaels is said to have harbored dreams of classy, sophisticated moviemaking — a modern version of Pride and Prejudice is mentioned — but his efforts on the big screen have netted little more than reheated leftovers of SNL material, such as Superstar or A Night at the Roxbury.

Is Michaels serious when he claims the mindless Chris Farley romp Tommy Boy is “a rough version” of his life? For that matter, is Morrison serious when she asserts that the same movie has acquired “a kind of a cult status”? To quote Peggy Lee, is that all there is? Michaels sounds wary as he tries to retain his show’s alleged “plague on both your houses” spirit of nonpartisan humor amid a cast beset by Trump hatred. Only a defeated man would consent, as Michaels did, to Kate McKinnon in her Hillary Clinton regalia dolefully singing Leonard Cohen’s “Hallelujah” on the episode following the 2016 presidential election. “It’s the hardest thing for me to explain to this generation that the show is nonpartisan,” Michaels said.

Once it winds its way past the genuinely exciting and innovative origins of SNL, the book itself seems increasingly like a case of special pleading on behalf of its subject. To cite one example, the antic lunacy of Saturday Night Live and the genteel reserve of the New Yorker magazine seem miles apart. But Morrison, the articles editor of the New Yorker, is weirdly determined to thread her magazine through the story: Michaels is described as wanting his show “to feel like an issue of The New Yorker.” Magazine stalwart Lillian Ross makes multiple cameo appearances while researching a profile of Michaels. And, most astonishingly, Michaels is said to have persuaded himself that much-loved editor William Shawn might tap him to take over the magazine. “The problem with the idea of being the editor of The New Yorker was that I have a need for action,” Michaels said, as though the idea was not unspeakably peculiar apart from his expressed disinterest in the job. You get the picture. Here and elsewhere, Morrison errs in taking and treating her subject too seriously. Is it not enough that Michaels concocted a show with such wonderful instances of outrageousness as Belushi and Morris’s Killer Bees and Rachel Dratch’s Debbie Downer, and that he offered the Beatles a couple thousand bucks to reunite? Must he also be William Shawn’s successor in spirit?

All the same, Morrison’s book is likely to stand as one of the most substantial works to emerge about our infatuation with SNL. Our culture is saturated with books, specials, and even the occasional feature film, last autumn’s Saturday Night, that commemorate the real and imagined greatness of SNL. But Morrison’s book, flaws and all, sets itself apart from the horde for being a real biography of the show’s inimitable prime mover.

Peter Tonguette is a contributing writer to the Washington Examiner magazine.