For those of us who grew up in the 1980s and ’90s, Lynne Reid Banks’s Indian in the Cupboard novels held something of the same appeal as Steven Spielberg’s E.T. the Extra-Terrestrial or The Goonies. Each centers on smart, sensitive children who happen upon something secret and unshareable with the grown-up world: a space creature in E.T., a treasure map in The Goonies, and a figurine-turned-real-man in Banks’s books.

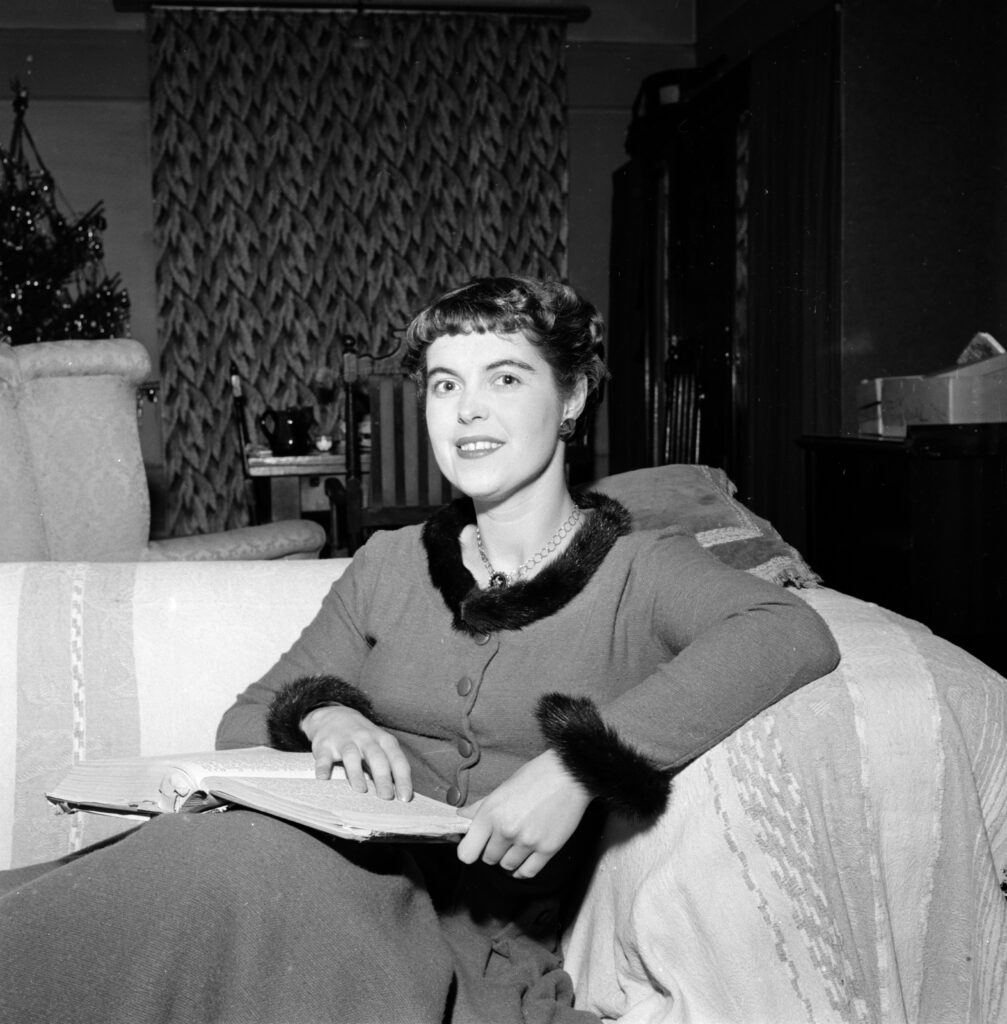

Banks, who died on April 4 at age 94, earned a permanent place in the hearts of millennials with her charming series. The success of the original book, 1980’s The Indian in the Cupboard, shepherded a set of sequels written over the next two decades: The Return of the Indian (1986), The Secret of the Indian (1989), The Mystery of the Cupboard (1993), and The Key to the Indian (1998).

The series was sustained by Banks’s simple yet bewitching premise: A little boy named Omri, whose name was borrowed from one of the author’s sons, receives a pair of rather wanting birthday gifts: a plastic toy Indian and a secondhand medicine cabinet. Yet, when situated inside the cabinet, the toy is given all the properties of life, albeit in miniaturized form: He breathes, he talks, he sleeps, he eats, and he fights.

“This Indian — his Indian — was behaving in every way like a real live Indian brave,” Banks writes early in the first novel, “and despite the vast difference in their sizes and strengths, Omri respected him and even, odd as it sounds, feared him at that moment.”

In concocting this flight of fancy, Banks was advancing the tradition of British fabulists like C.S. Lewis and J.R.R. Tolkien. Born in London in 1929, Banks acquired a taste for the fantastic thanks to her Irish mother, an actress. “I was brought up to think we really shared the world with little people, fairies, and elves and so on,” Banks told the New York Times in 1993. Her father was a physician.

Just a year after her birth, her family, seeking to avoid imperilment during World War II, pulled up stakes for a city in Saskatchewan, Canada, where they remained until 1945. “Saskatoon was a thriving metropolis, but there was still a very strong, pioneering Western flavor to the town,” Banks told the New York Times, crediting that background with her subsequent interest in the milieu that later informed The Indian in the Cupboard.

Yet, as Banks embarked on her professional life, her distinctive melding of British fantasy and North American iconography was still a long way off. Seeking to emulate her mother, Banks trained at the Royal Academy of Dramatic Art, but she settled on the less glamorous trade of television journalism. By her account, she wrote her first novel — the acclaimed, and very adult-oriented, The L-Shaped Room — during her “downtime” while employed at ITN.

Published in 1960, The L-Shaped Room in no way presages Banks’s later works for children: The book revolves around a young woman whose status as an unwed mother-to-be proves a significant complication as she attempts to forge a life for herself. In 1962, as a kind of female answer to the “Angry Young Man” genre of British cinema, the book was turned into an acclaimed movie starring Leslie Caron.

Confronted with such success, most authors would do the talk-show circuit and churn out similar books, but the adventuresome Banks made the decision to relocate to a kibbutz, where her eventual husband, the gifted sculptor Chaim Stephenson, was living. The couple married in 1965 and were parents to three children. In 1971, Banks and her family left Israel for her home country, but the marriage endured. Stephenson died in 2016.

Then came The Indian in the Cupboard, the outlines of which, the author asserted, originated as a bedtime story for her son Omri. Because so many years had passed since the triumph of The L-Shaped Room, the widespread popularity of The Indian in the Cupboard must have seemed as out of the blue as the instant success of J.K. Rowling’s Harry Potter books.

CLICK HERE TO READ MORE FROM THE WASHINGTON EXAMINER

Banks and Rowling have something else in common: They both attract critics. Unbelievably, the Indian in the Cupboard books — a wonderfully human, generous-spirited series ideally suited to children — were attacked for, in the words of Louise Erdrich, being akin to “Orwellian allegories of childish imperialism.” Perhaps conceding too much, Banks acknowledged some limitations in her writing. Of the title character, she said, “By today’s progressive rules, I misnamed him.” But she held firm against the proposed addition of a “warning label” to her books: “I said they may not meddle with my book,” she told the Independent in 1995. “I will sue them through every court.”

To the credit of a pre-“woke” Hollywood, The Indian in the Cupboard was made into an appealing movie in 1995. Muppets artisan Frank Oz directed, and E.T. scribe Melissa Mathison adapted the novel, faithfully and lovingly. It’s a good film and deserved sequels (Netflix, are you listening?), but devotees of Banks needn’t rely on Hollywood to get their fill of their favorite author. The Indian in the Cupboard and its offspring remain as delightful as ever.

Peter Tonguette is a contributing writer to the Washington Examiner magazine.