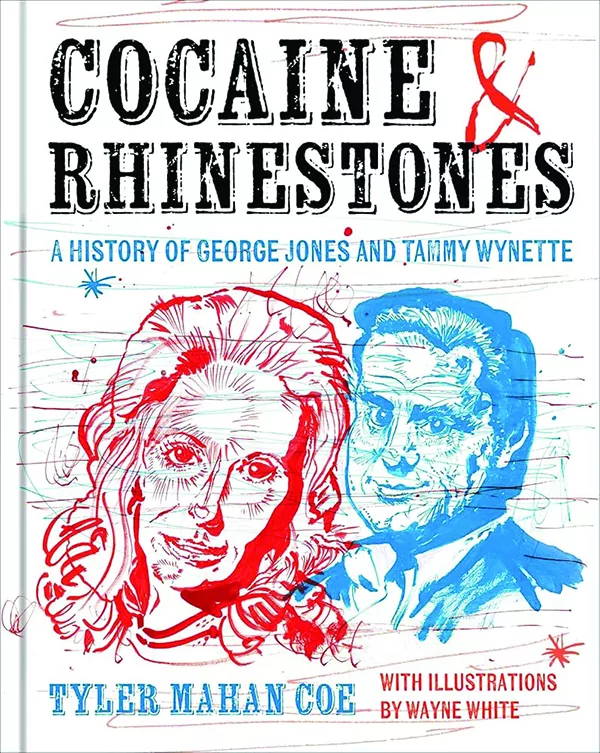

When Johnny Cash was asked who his favorite country singer was, he would often reply, “You mean, besides George Jones?” Another renowned country artist, Merle Haggard, called Jones’s voice “one of the greatest instruments ever made,” comparing it to a Stradivarius violin. Jones became a living legend in his own lifetime. But as Tyler Mahan Coe highlights in Cocaine and Rhinestones: A History of George Jones and Tammy Wynette, Jones would become well known for the turbulent life that he lived off stage.

George Jones was a man blessed with rare talent. But he was also a man beset by demons. And those demons were shared by another country star, Tammy Wynette, his on-again, off-again paramour. Together, they captured the top of the charts and popular attention for much of the 1970s. Their relationship became a legend itself, with soaring highs and crushing lows. But as Coe makes clear, the low notes dominate. There is, he warns, “more pain and heartache” than “there is happiness.”

Jones was born in 1931 in a part of East Texas known as Big Thicket. This was where “the poorest of folk were driven by dire economic circumstances to perform dangerous work and scratch out whatever life they could from the land.” Jones’s father was a hard-drinking laborer who was prone to going on benders and beating his children. He would often get drunk and make his children perform songs for him. If young George quit playing too early, he would face a beating. For some people, this might create an aversion to music, but for George, the opposite proved to be the case.

During the Depression, the Jones family listened to the Grand Ole Opry on the radio. Roy Acuff and Ernest Tubb were early favorites. But for George, Hank Williams would eclipse them both. By the age of 15, George fled home and began living a life as a vagabond, traveling and singing in honky-tonks long before he was old enough to drink. Jones would mimic Acuff’s emotional delivery and echo Williams’s rollicking sound. A job at a radio station led to a chance encounter with Williams, then the country’s biggest star, who advised him to drop the imitations and work on developing his own voice. After a brief stint in the Marine Corps, Jones would do just that.

Jones had tried several other careers, from painting houses to driving delivery trucks to working in a funeral home, until he “eventually decided that he was either going to make it in life as a country singer or he wasn’t going to make it at all.” He traveled across the United States, guitar in hand, playing at whatever club would have him. He played under various pseudonyms and dipped his toe into other genres, including early rock ‘n’ roll. His initial recordings and studio sessions were clearly done on a budget. But eventually, his natural talent shone through, and Jones was opening for Elvis Presley and others.

By the early 1960s, Jones was a bona fide star. Even his earliest influence, Roy Acuff, said he wished he could sing like Jones — and for good reason. Jones’s unique phrasing and emotional delivery earned him acclaim and success. He became the only star in country music history to have a top 40 hit over the course of seven decades. But the ensuing years would be rocky.

“All my life, I’ve been runnin’ from something,” Jones once told the Chicago Tribune. “If I knew what it was, I could run in the right direction. I know where I want to go, but I always seem to end up goin’ the other way.” Jones’s newfound stardom was complicated by his insecurities. He suffered from severe stage fright and acute social anxiety. As he once said: “I never wanted to be a star and only occasionally wanted to be a performer. I always wanted to be a singer.”

He didn’t feel he deserved the fame and success he had garnered. Haunted by his impoverished upbringing, his newfound wealth embarrassed him. There are credible stories of Jones setting piles of cash on fire. He coped by drinking — a lot.

As Coe points out, Jones “began displaying what we’d recognize as early signs of alcoholism in Texas honky-tonks during the 1940s, when he was just a teenage survivor of child abuse, singing country music the way his drunk dad had forced him to under threat of another beating.” To some extent, this was encouraged by his various producers and backers, some of whom felt that Jones cut his best sessions while slightly buzzed. The trick, of course, was to make sure he didn’t drink too much. This was easier said than done.

By the mid-1960s or so, Jones was really hitting the bottle. Becoming a living legend didn’t help. Worse still, Jones’s well-known affinity for alcohol became part of that legend. Club owners wanted to drink with him, his songs about booze were often guaranteed chart-toppers, and fans bought tickets to his concerts knowing that it could very well be the last time they saw him. Jones had inherited Hank Williams’s fan base, and they all knew that Williams’s alcoholism led to his death in the backseat of a 1952 Cadillac convertible at the tender age of 29. Jones seemed intent on filling his idol’s boots.

This was around the time that Tammy Wynette set her sights on George Jones. Born Virginia Wynette Pugh in Mississippi, she was 9 months old when her father, a farmer who had fantasized about being a professional musician, died of a tumor that first made him blind before killing him. Virginia’s early life was turbulent. She was pregnant at 17 and couldn’t seem to hold a job. A gig waitressing at a honky-tonk in Memphis allowed her to indulge her love of music. Eventually, she made her way to Nashville, where legendary producer Billy Sherrill took an interest. While she technically wasn’t a great vocalist, she sounded different from other singers at the time. “There was,” Coe notes, “a unique pain in her voice, and she could take it from quiet to loud and back at the drop of a hat, hurtin’ the whole way.”

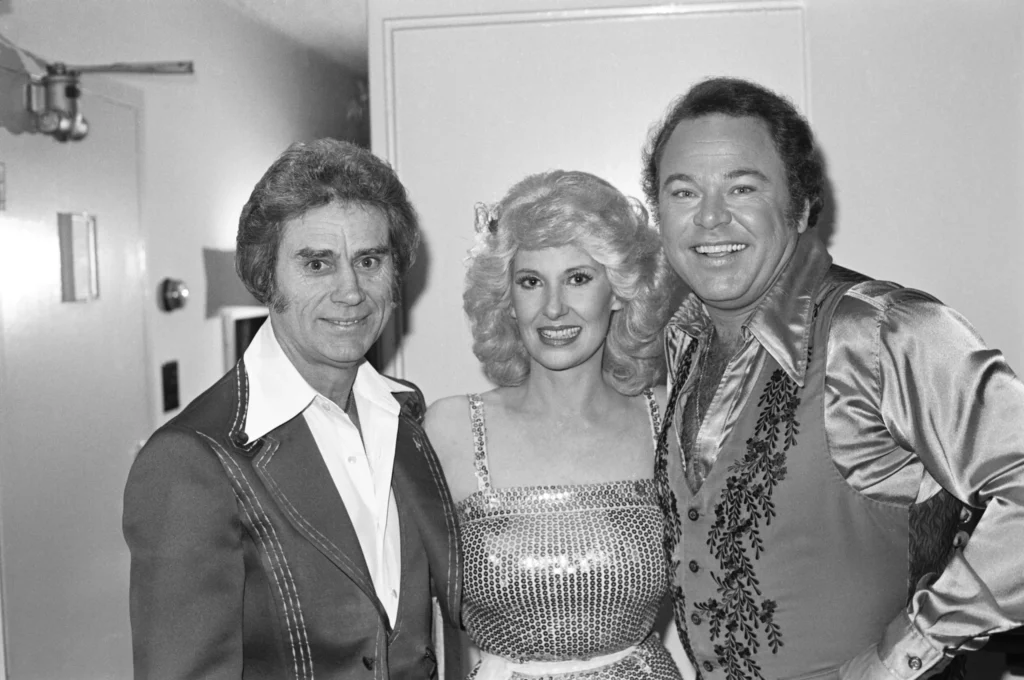

Unlike Jones, by the late 1960s, Wynette had achieved crossover success, with some of her songs making a splash on both the pop and country charts, perhaps most famously her anti-feminist anthem, “Stand By Your Man.” Indeed, of the 14 singles by women solo artists to go No. 1 Country in the 1960s, six were by Tammy Wynette. And she soon became determined to make Jones hers. That both were already married didn’t seem to stop them. It would be the third marriage for each of them, and it was turbulent from the start.

In songs and interviews, George adopted the narrative that Tammy’s love had saved him from his worst demons. “When we were onstage, we were in our own little heaven,” he would say. But in truth, neither could be saved from themselves. Wynette once said, “George is one of those people who can’t tolerate happiness.” But she could have been talking about herself, too. As Jones retreated into the bottle, Wynette soon became addicted to prescription drugs while also concocting bizarre stories about attempted kidnappings and stalkers for attention.

As artists, their duets were bestsellers. And the writers and producers consciously crafted songs that seemed to reflect their relationship as it played out across the tabloids. With songs such as “We’re Going to Hold On,” they seemed to be living out the lyrics they were belting. Early petitions for divorce were submitted, only to be withdrawn. But by 1975, after six years of marriage, they finally called it quits.

Wynette would go on to date Hollywood actors, other Nashville singers, and wealthy businessmen before embarking on a 44-day marriage and then another marriage with her controlling manager. Jones, meanwhile, turned to cocaine, his addiction becoming so bad that he was living out of his car and battling multiple personality disorder and severe paranoia.

“To simply say George Jones became a cocaine addict would be an understatement on the level of saying LeBron James plays basketball or Pablo Picasso painted pictures,” Coe writes. Cocaine and Rhinestones is fortunately peppered with similar moments of levity.

Coe is a good storyteller, colorfully weaving a tale that, at its core, is a tragedy. As Jones sang on his last album, “If life were like the movies, I’d never be blue.” But if that were true, we’d probably have missed out on some of the most memorable songs in country music.

CLICK HERE TO READ MORE FROM THE WASHINGTON EXAMINER

Sean Durns is a Washington, D.C.-based writer.