Nearly half a million immigrant children have arrived without a parent at the nation’s borders during President Joe Biden‘s tenure, a milestone no other administration has come close to hitting.

In the three years since Biden took office and stopped returning to Mexico unaccompanied minors, a whopping 464,922 children have been encountered by U.S. Customs and Border Protection police nationwide, according to a Washington Examiner analysis of federal data from Feb. 1, 2021, through Jan. 31, 2024.

“The increase started when the Biden administration announced they were exempting children from Title 42 and announced that we would not be removing children,” said Rodney Scott, the former Border Patrol chief under the Trump and Biden administrations who is a distinguished senior fellow for border security at the Texas Public Policy Foundation, a conservative think tank in Austin.

A leading aid organization for child immigrants, Kids in Need of Defense, said the sudden implosion of children and teenagers crossing the southern border alone over the past several years was fully anticipated because they were barred from seeking asylum as a result of U.S. measures implemented at the border during the coronavirus pandemic.

“There had basically been a backup at the border. … It was like releasing a pressure valve. So all these kids who have been waiting in really terrible conditions in northern Mexico were finally able to present for protection,” said Jennifer Podkul, KIND’s vice president for policy and advocacy. “People working on this issue were not surprised at all.”

But that influx of minors in early 2021 has not gone away in three years — it’s become the new normal.

A history of child migration

Children did not begin migrating to the United States in a significant fashion until a decade ago following changes to U.S. law.

In 2008, the William Wilberforce Trafficking Victims Protection Reauthorization Act declared that unaccompanied children from Canada and Mexico who arrived at the border would be immediately returned, but children from other countries would be taken into custody as possible trafficking victims.

For cartels, transnational criminal organizations that profit thousands of dollars per person they smuggle into the U.S., it was a money-making opportunity because it meant a new population of people who would likely not be turned away at the border could pay to be smuggled in.

In the summer of 2014, the Obama administration experienced the first surge. In fiscal 2014, Border Patrol apprehended 68,000 solo children. That figure was record-breaking at the time and then dissipated, but it spiked during the Trump administration when 80,000 children arrived in 2019. It dropped as the pandemic began in early 2020.

The Biden effect

As White House administrations shifted from Trump to Biden in early 2021, border policies changed, and travel restrictions were lifted in some places. Migration subsequently increased around the world, including among children heading to the U.S.

In February 2021, the Biden administration chose to stop returning children to Mexico, as had been the case since March 2020. Within weeks, children began arriving by the hundreds per day.

In 2021, Border Patrol apprehended 144,000 children, federal data show. In 2022, 149,000 children arrived alone.

In 2023, the number dropped to 131,000, and it is on track to hit 125,000 by the end of fiscal 2024 in September.

Roughly 95% of the 464,922 total children crossed the southern border illegally, compared to 5% who made the journey and surrendered to customs officers at ports of entry.

Why are children coming at alarmingly high rates?

A 2023 report by the Council on Foreign Relations identified environmental challenges, chronic violence, and a lack of economic opportunity as top factors that prompt Central American residents to flee.

“Most others have historically come from Mexico, where the homicide rate is at near-record levels amid a long-standing war against drug cartels. Perceptions that Biden is more welcoming than his predecessor have also driven migration, some observers say,” the Council on Foreign Relations researchers Diana Roy and Amelia Cheatham wrote in the report.

Ron Vitiello, a former CBP senior official who ran on the Republican ticket for Senate in Virginia this cycle, said during a 2018 press conference that legal loopholes, such as those in the trafficking victims law, were not protecting children immigrants but enabling and enticing them.

“If you come as a family unit or an unaccompanied minor, the way the policy loopholes and the legal framework is set up [is so] that we turn these folks over,” Vitiello said. “They’re eventually released into our communities, and so that encourages others to come.”

Are they smuggled or trafficked?

Not all children who go to the border alone come of their own volition.

“The total population of unaccompanied and accompanied children includes both just traditional, smuggled aliens, as well as trafficking,” Scott said in reference to children who may owe smugglers thousands of dollars for getting them to the U.S.

“The alien does not realize yet that they’re being trafficked, and we’re not doing good interviews,” Scott said. “It’s extremely difficult to detect trafficking at the border.”

Podkul works extensively with children and recently traveled near the Darien Gap, a massive jungle that connects Panama and Colombia that immigrants must pass through to get from South America to Central America on their journey north.

First, some travel with extended family members, such as an uncle or cousin, or family friends. However, under U.S. law, that adult is not legally the child’s guardian or parent, making the child an “unaccompanied minor.”

Second, children may start out traveling with a parent but get separated for reasons out of their control, including smugglers who “divvy up families” as they put people on buses or through stretches of the Darien Gap.

“There’s kids who are fleeing abuse at home. So they’re fleeing an abusive parent, and that’s why they’re deciding to come and make the journey, or other dangers at home,” Podkul said.

Finally, children from Central America, in particular, may choose to leave their families before getting to the age when gangs, such as MS-13, will recruit them, often against their will and through deadly retribution if they refuse.

“They’re leaving to protect their younger siblings or their parents who they know the gangs will start going after the family members to pressure the kid,” Podkul said. “It’s kind of a benevolent act of the kid to protect their family.”

Who are these children?

In 2023, slightly more than two-thirds of unaccompanied minors were between the ages of 15 and 17, according to Department of Health and Human Services data. Of the remaining, children were between the ages of 0 and 12, 19%, or 13 and 14 years old, 12%.

The percentage of children arriving at the border from countries other than Mexico, Guatemala, Honduras, and El Salvador has gone from less than 5% a decade ago to 13% last year. Three out of five child immigrants were boys.

“China, Afghanistan, India, Uzbekistan — the numbers of countries and nationalities who are coming through is increasing,” Podkul said in a general comment about who is transiting the Darien Gap area.

Children remained in government custody for an average of a month before being released into the U.S., according to federal data.

What happens when a child crosses the border?

Under normal circumstances, children without parents are taken into Border Patrol custody after they walk across the border and are to be transferred within 72 hours to HHS, which has jurisdiction over caring for children.

But the influx of children prompted the Biden administration to take emergency action responding to the arrivals and has continued to despite Republicans’ calls to deter more children from coming. Biden created tent cities at various spots up and down the border where unaccompanied children could be housed, including in Texas cities El Paso, Carrizo Springs, and Pecos.

HHS would detain each child before releasing the child to a sponsor in the U.S. Children often arrived at the border clutching a paper with a phone number on it.

HHS was referred 118,938 children in 2023, most of whom passed through its pop-up tents before being released.

“We really need to focus more on what’s pushing kids and how do we address that?” Podkul said. “Just because we have a law that might be protective law or something that’s some sort of magnet, that’s not going to outweigh the risks that these kids absolutely know that they’re taking by making this journey.”

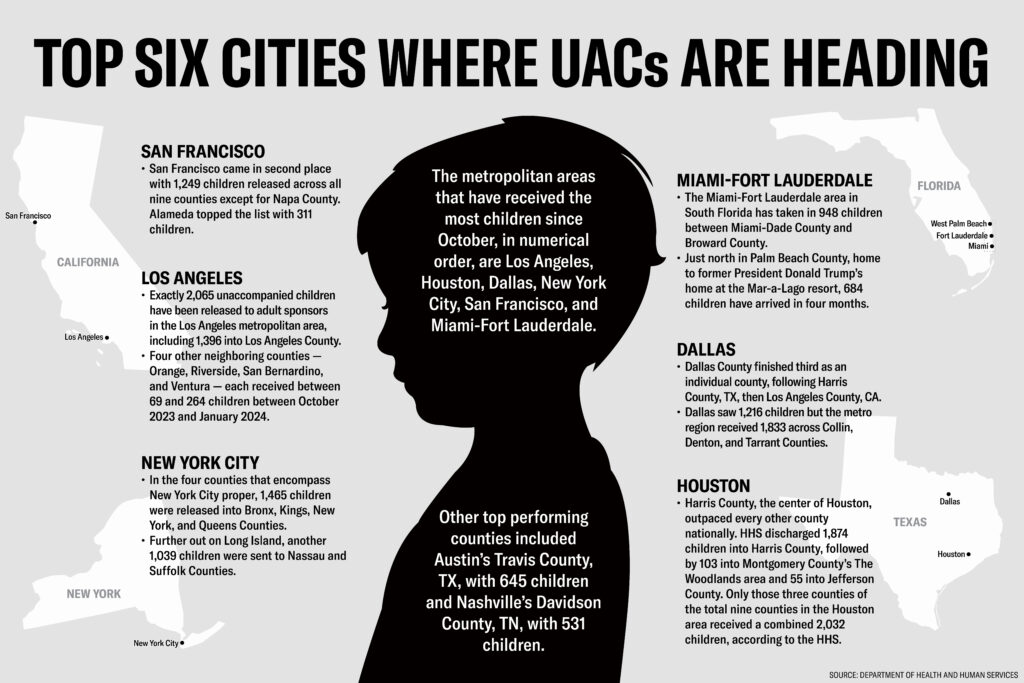

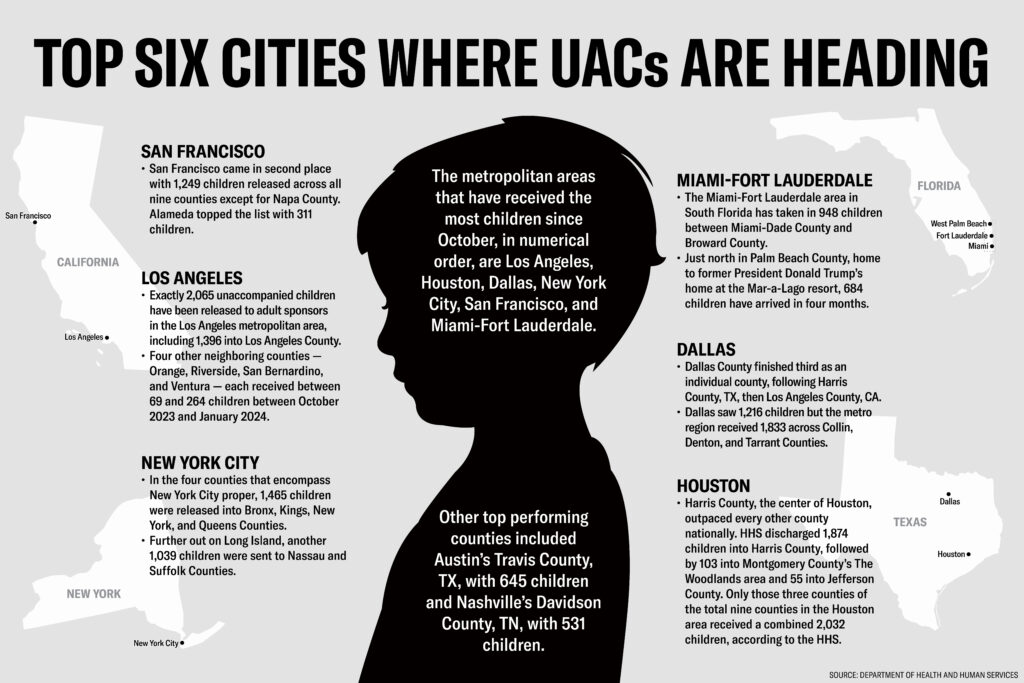

Where does that child go from the border?

Under the Biden administration, HHS releases data every weekday on the number of unaccompanied minors who were apprehended at the border the previous day and transferred from Border Patrol into HHS custody.

“As soon as children enter [Office of Refugee Resettlement] care, they are put in contact with their parents, guardians, or relatives, if known, and the process of finding a suitable sponsor begins. Most sponsors are a parent or a close family relative living in the United States,” HHS said in a statement. “While ORR programs are looking for sponsors, children are provided age-appropriate care and wraparound services in one of the 289 facilities and programs in 29 states funded by ORR.”

It’s one reason Republicans have voiced concern about “secret flights,” in which children are flown from border states to destinations nationwide where HHS has facilities to hold children while a sponsor can be found.

HHS said “most” sponsors are parents or close relatives. If a family member cannot be found, an unrelated adult will receive the child.

HHS conducts criminal public records checks on the specific sponsor, though a sex offender registry check is not required by law.

The child may remain in the U.S. through immigration court proceedings for illegally entering at the border. Cases can take a couple of years to a decade to resolve.

Where does it go from here?

Of the more than 464,000 children who arrived at the border alone under Biden, HHS has discharged 391,000 children into the country between 2021 and January 2024. Fiscal 2021 began shortly before the November 2020 election while Donald Trump was in office.

The New York Times reported last spring that HHS had attempted to follow up with children after they were released to sponsors but could not reach 85,000 sponsors.

Last May, 75 House Republicans accused Biden officials of knowingly and recklessly discharging unaccompanied children to adults across the country and doing nothing to find the children.

The letter referenced reports by the New York Times that found children were being extorted by smugglers to pay off the thousands of dollars they owed. Children were forced into indentured labor within the U.S., even sex work.

CLICK HERE TO READ MORE FROM THE WASHINGTON EXAMINER

In one case, a 13-year-old boy was sent to live with a man whom he had met through Facebook, only later to be threatened and extorted.

The White House did not respond to a request for comment.