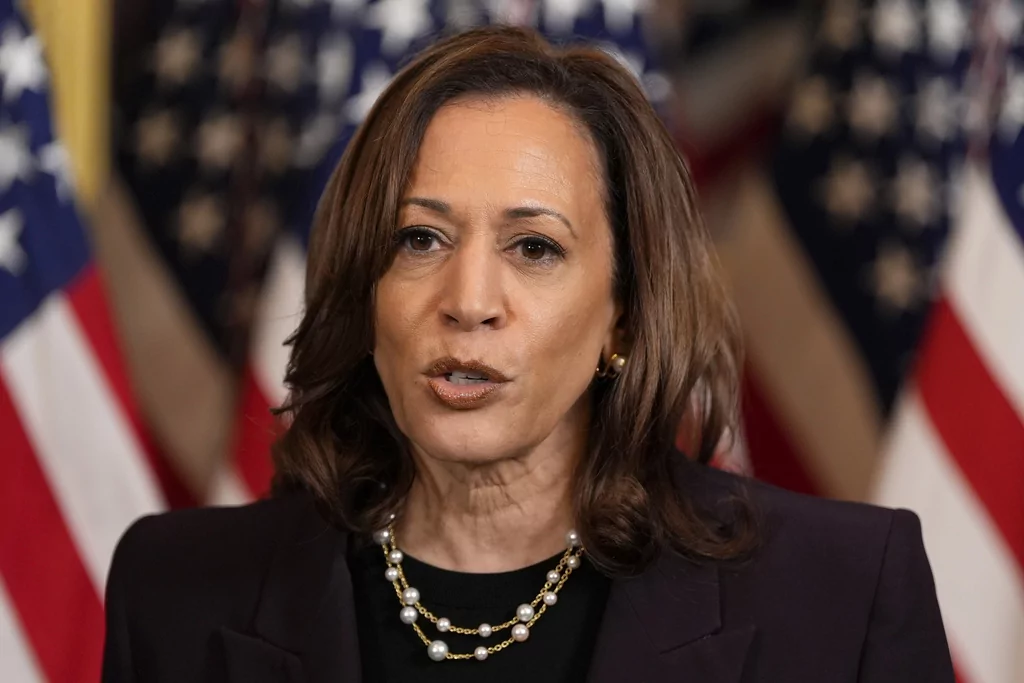

Kamala Harris’s ascension to the top of the ticket has energized the Democratic base and refocused Republican attack lines. With less than 100 days to go until the election, defining Kamala Harris will take place at lightning speed. This Washington Examiner series will take a closer look at various aspects of her campaign and persona. Part one is on “Kamala the cop.”

Vice President Kamala Harris may be running as America’s “top cop” against former President Donald Trump, but her prosecutorial past is complicated, at best, and littered with land mines.

Harris has framed her potential matchup with Trump as a tough prosecutor running against a greedy criminal.

“I took on perpetrators of all kinds, predators who abused women, fraudsters who ripped off consumers, cheaters who broke the rules for their own game,” Harris said at a Wisconsin rally. “So hear me when I say I know Donald Trump’s type.”

But there’s a lot to unpack when it comes to Harris, her background, allegations of prosecutorial misconduct, and flip-flopping on issues.

Harris rose through the prosecutorial ranks. She was elected district attorney of San Francisco, California’s attorney general, and vice president of the United States. Today, she’s on the cusp of securing the Democratic nomination for president.

“During Harris’ runs for California attorney general and U.S. Senate, I saw firsthand what kind of candidate she can be: tough, formidable, disciplined,” wrote Dan Morain, author of Kamala’s Way: An American Life.

“Without a doubt, Republicans should wish they had stopped her when they had their best chance,” he said.

Playing both sides

Harris’s opinions and actions, at times, have put her at odds with both sides of the political spectrum. To those on the Right, she wasn’t tough enough. To those on the Left, she was too tough and didn’t do her job speaking up for marginalized communities. She’s also been accused of being a social and political climber, fixated on getting power rather than getting the job done.

“I hope her past comes back to haunt her,” California-based civil rights attorney Harmeet Dhillon told the Washington Examiner. “She has a terrible record dating from her broken promises of being a tough-on-crime district attorney.”

Cop killer

One of Harris’s most controversial moments came three months into her tenure as San Francisco district attorney in 2004 when a gang member killed a police officer using an AK-47. Three days after the grisly murder, she announced she would not seek the death penalty. The backlash was swift and brutal, not only from law enforcement but also from fellow Democrats.

The late Sen. Dianne Feinstein (D-CA) stood in front of thousands of mourners at Officer Isaac Espinoza’s funeral and urged Harris, who was sitting in a pew at the front of the cathedral, to change her mind. Former Democratic Gov. Jerry Brown, who was mayor of Oakland at the time, was among those standing in ovation to Feinstein’s comments.

It got so bad that the state attorney general threatened to take over the case, and then-Sen. Barbara Boxer (D-CA) asked the Justice Department to step in.

Harris, the first person of color elected as San Francisco’s district attorney, did not budge.

She said the death penalty discriminated against poor and black people and seeking it against the cop killer would not prevent more deaths.

“She let everybody down, the city, the family,” Dhillon said. “And that was like a high point for her and it just went down from there.”

Nicole Castronovo, a Los Angeles-based criminal defense lawyer, called Harris’s refusal to seek the death penalty “a huge misstep.”

“At the end of the day, she is an extension of law enforcement and she lost a lot of credibility with them,” Castronovo told the Washington Examiner. “She forever lost endorsements from police unions who would normally endorse a prosecutor. It was one of her biggest mistakes politically.”

But that wasn’t the only decision Harris made that angered San Franciscans.

Catholic church: Sex abuse victims

Joey Piscitelli claimed Harris ignored him and many sex abuse victims of the Catholic church back in the 2000s.

Piscitelli, who was then a spokesman for clergy sex abuse victims, said Harris didn’t respond when he wrote to tell her that a priest who had molested him was still preaching at a local church. He was once again iced out five years later when he urged her to release records on accused clergy to help alleged victims who were filing lawsuits.

“She did nothing,” said Piscitelli, who went on to become the Northern California spokesman for SNAP, the Survivors Network of those Abused by Priests.

Catholics made up large voting blocs in San Francisco and across California.

“There’s a potential political risk if you move aggressively against the church,” Michael Meadows, a Bay Area attorney who has represented clergy abuse victims, told the Associated Press at the time. “I just don’t think she was willing to take it.”

Before Harris was elected district attorney, a U.S. Supreme Court decision made it impossible to pursue criminal prosecutions of child sexual abuse cases after statutes of limitation had expired. For many victims, that left lawsuits in civil court as the only path for seeking justice.

After becoming district attorney, lawyers representing abuse survivors in civil cases asked her office to release church records on abusive priests. The list had been gathered by her predecessor, Terence Hallinan.

Harris refused.

“It would be virtually impossible to release records without compromising the identity of the victims,” two of her top aides wrote in a joint letter.

The decision was met with a lot of pushback.

“What she was saying was utter nonsense,” Meadows said. “All she had to do was redact any identifying information.”

Crime lab scandal

A few years later, Harris was caught up in another scandal that threatened to upend her run to become California’s attorney general.

One of her top deputies had emailed a colleague about a crime lab technician who had become “increasingly UNDEPENDABLE for testimony.” The tech allegedly took cocaine home from the lab and possibly tainted evidence in hundreds of cases.

Despite knowing this, neither Harris nor those working under her had informed defense attorneys despite rules in place requiring them to do so.

In a scathing ruling in May 2010, Superior Court Judge Anne-Christine Massullo said Harris’s office violated defendants’ rights by hiding damaging information and was indifferent to demands that it account for its failings.

Harris wasn’t happy.

First, she blamed the police for not informing defense lawyers. Then, she publicly estimated that only 20 cases would be affected. She also accused Massullo of being biased because the judge’s husband was a defense lawyer. But as public frustration grew, Harris’s office took the rare step of dismissing about 1,000 drug-related cases.

“She lost the trust of a lot of people,” San Francisco-based programmer Lucy Longhorn told the Washington Examiner. “Her denial. The 180. It gave us whiplash. Then she had the audacity to run for attorney general.”

Chris Kelly, former Facebook general counsel and Harris’s opponent in the Democratic primary, slammed her for her handling of the lab tech case and said Massullo’s ruling showed Harris had “systematically violated defendants’ civil and constitutional rights.”

Cutting deals and withholding evidence

Despite his comments, Harris won the attorney general’s race in 2010, becoming the first black woman to do so.

But as California’s top cop, Harris and her office were criticized more than once for prosecutorial misconduct and defending convictions in cases where there was evidence of innocence.

One case involved Johnny Baca, who has been tried twice for the 1995 murders of John Mix and John Adair.

Prosecutors made a deal with a jailhouse snitch named Daniel Melendez who testified Baca confessed to the crime behind bars. In exchange for his testimony, prosecutors would shave time off his sentence. They didn’t tell Baca’s lawyer, knowledge he was entitled to so he could cross-examine Melendez on his motives.

Baca’s lawyer asked Melendez under oath if he was receiving anything from prosecutors in exchange for his testimony. He lied and said no. A prosecutor then backed up Melendez’s story, also lying in court that he did not cut Melendez any favors. After the details were released, the attorney general’s office effectively moved to drop the case.

“This decision, as with Harris’s belated implementation of a Brady policy, came only after she had been publicly and humiliatingly backed into a corner by a trio of federal judges,” Nicole Allan wrote in the California Sunday Magazine in 2019. “And, as had been the case with the crime-lab scandal, it unfolded during the early stages of a high-profile campaign.”

Defund the police

Before becoming vice president, Harris once again turned her back on law enforcement, voicing her support for the “defund the police” movement that spread from coast to coast in 2020.

During a June 9, 2020, radio interview on Ebro in the Morning, she said the movement “rightly” called out the massive amounts of money being poured into police departments and suggested it would be better spent on community services.

“Defund the police, the issue behind it is that we need to reimagine how we are creating safety,” she said on the New York-based radio show. “And when you have many cities that have one-third of their entire city budget focused on policing, we know that it is not the smart way and the best way or the right way to achieve safety.”

But once Harris signed on as President Joe Biden’s running mate she was singing a different tune.

By October 2020, her former press secretary, Sabrina Singh, told reporters, “Joe Biden and Kamala Harris do not support defunding the police, and it is a lie to suggest otherwise.”

Her flip-flop is right on brand, Dhillon, a Trump supporter, said. “This woman is now standing in front of cameras posturing as some kind of civil rights hero,” she said. “It makes me sick to my stomach as a civil rights lawyer.”

CLICK HERE TO READ MORE FROM THE WASHINGTON EXAMINER

But others, like Democratic political strategist David McLaughlin, say Harris’s past missteps aren’t likely to damage her campaign going forward and suggest she “absolutely lean in” to her past.

“I’m all the way across the country but I’ll tell you this, she won elections as attorney general, senator, and then vice president with whatever this is being known and it didn’t seem to resonate with the voters of California and the voters of America,” McLaughlin, who is based in Georgia, told the Washington Examiner.