The most glowing admirers and fiercest detractors of Senate Minority Leader Mitch McConnell (R-KY) agree on one thing — his ability to move the federal judiciary in a more conservative direction.

McConnell is set to step down from his leadership post after the November elections, capping a record 18 years as party leader, six heading Republican majorities and 12 playing defense in the minority. Even though McConnell was majority leader only about a third of that time, he played a crucial role in pushing through judicial nominees put forward by then-President Donald Trump and, just as importantly, blocking judicial candidates nominated by then-President Barack Obama.

McConnell led the 10-month-plus 2016-17 effort to block Obama’s Supreme Court nominee, then-federal appeals court judge Merrick Garland, from confirmation following Justice Antonin Scalia’s 2016 death. Trump’s eventual replacement for Scalia, now-Justice Neil Gorsuch, was the first of three high court nominees who helped cement the current 6-3 majority, one that changed abortion law nationwide in the Dobbs v. Jackson Women’s Health Organization case, which effectively let states decide their own rules on when and whether to allow the procedure.

McConnell will remain in the Senate for the final two years of his six-year term, likely finishing a 42-year career in the chamber. McConnell’s colleagues said he’s a model for how to proceed on judicial nominees.

“His successor would do well to prioritize the federal judiciary in the same way,” Sen. Lindsey Graham (R-SC) told the Washington Examiner.

Graham lauded McConnell, 82, as “one of the strongest Senate leaders on national security in history” who “unashamedly associates himself with the party of Ronald Reagan.”

Not surprisingly, critics of conservative jurisprudence, such as Brennan Center for Justice senior fellow Caroline Fredrickson, take a dim view of McConnell’s tenure as GOP leader, though even they acknowledge his effectiveness.

“His biggest achievement in the Senate has been to cement Trump’s impact on the federal judiciary, helping him get three Supreme Court nominees confirmed as well as a record number of lower court judges,” Fredrickson wrote for Politico on March 1.

“McConnell played hardball in bending and abandoning rules that stymied Republican judicial nominees, while obstructing and slowing nominees coming from Democratic presidents,” added Fredrickson, a former president of the liberal American Constitution Society. “He has had no compunction or romanticism about Senate traditions and procedures — and I think that approach now characterizes his party.”

Beginning of the judicial wars

McConnell’s judiciary agenda can be traced back to his first Senate term during the last two years of Reagan’s presidency. In 1987, after Senate Democrats and a handful of Republicans defeated Supreme Court nominee Robert Bork, McConnell warned that if a Democratic president “sends up somebody we don’t like” to a Republican-controlled Senate, the GOP would follow suit.

It took a while for that tit-for-tat pattern to settle into the Senate. After famously contentious confirmation hearings, the Democratic-majority Senate in October 1991 confirmed 52-48 Justice Clarence Thomas, who had been nominated by President George H.W. Bush.

And Senate Republicans largely deferred to the tradition of backing Supreme Court nominees from presidents of other parties if they were qualified despite often vehement disagreements over judicial philosophies. President Bill Clinton got to make a pair of Supreme Court nominations during the first two years of his tenure. Justice Ruth Bader Ginsburg breezed through on a 96-3 vote in the Democratic-majority Senate. A year later, Justice Stephen Breyer was confirmed with ease, 87-9, a few months before Republicans won control of the chamber in the 1994 elections. McConnell voted for both Democratic nominees.

But the political landscape on judicial nominations had changed dramatically by the time the next Supreme Court openings appeared, a full 11 years later. With Republicans holding the majority, many Senate Democrats balked at but couldn’t stop the confirmations of Chief Justice John Roberts and Associate Justice Samuel Alito a few months later.

The intervening years saw attitudes toward federal judicial nominees harden on both sides when it came to lower court vacancies. McConnell, as Senate whip under his predecessor as majority leader, former Sen. Bill Frist, a Tennessee Republican, took a leading role in attempting to push through judicial nominees from President George W. Bush.

Many made it through and became household names in the process, such as Priscilla Richman (previously Priscilla Owen), confirmed over Democratic opposition to the 5th Circuit Court of Appeals in 2005, and Janice Rogers Brown, who was a judge on the District of Columbia Court of Appeals from 2005-17 and had overcome Democratic resistance to her nomination.

Though Senate Democrats in 2003 successfully filibustered the nomination to the D.C. appeals court panel, considered a stepping-stone to the Supreme Court, of Miguel Estrada, an attorney in private practice, leaked internal memos to Democratic Senate Whip Richard Durbin (D-IL) mentioned liberal interest groups’ desire at the time to keep Honduras-born Estrada off the court because of his potential to be a future Supreme Court nominee and because his Latino roots would make his nomination difficult to oppose.

A decade later, fierce judicial fights were the norm. McConnell warned in 2013 not to ratchet them up further. In 2013, McConnell said on the Senate floor to then-Senate Majority Leader Harry Reid, “You’ll regret this,” after the Democratic senator from Nevada ended the filibuster on federal judicial nominees with a carve-out for Supreme Court justices.

Reid was moving to dissolve the 60-vote threshold for judicial nominations after frustrations over Republicans blocking Obama’s nominees, a precedent that had been in place since his party began filibustering in 2003. McConnell and the Senate GOP, then in the minority, opposed the move. After Reid blew up the judicial filibuster, Republicans took control of the Senate in 2014 and brought Obama’s judicial nominees to a grinding halt.

McConnell’s success extended beyond appointments as he strategically leveraged vacancies and lowered confirmation thresholds, enabling Trump’s landmark impact on the federal courts. Obama managed to confirm 323 judges, about as many as George W. Bush, with both in office for eight years. Meanwhile, Trump benefited from 105 vacancies left by Obama and confirmed 234 federal judges in just four years, including reshaping about a third of the appellate courts.

Brian Darling, a GOP strategist and former Senate aide, described McConnell as someone who has “always been a leader who has respected the rules and tried to preserve the rules” and who was “smart about it.”

“And when Reid changed the rules to make it a simple majority to shut down debate on nominations, with the exception for the Supreme Court, and it came down to a Trump appointee being potentially blocked on a filibuster, he made that rule consistent by making the rule so that it was a simple majority to shut down debate on nominations to the Supreme Court,” Darling added.

Hours after Scalia’s death on Feb. 13, 2016, McConnell announced during a U.S. Virgin Islands trip that he would block Democratic efforts to fill the justice’s seat. When Trump took office in January 2017, he nominated Gorsuch to the Supreme Court. McConnell-led Republicans lowered the threshold that year for confirming Supreme Court justices from 60 to 51 votes.

“I think that’s the most consequential thing I’ve ever done,” McConnell told the New York Times in 2019 of his decision to block Garland’s confirmation.

That decision, coupled with two other nominees McConnell would oversee as majority leader under the Trump presidency, set the course for a host of right-leaning courtroom victories in recent years, including allowing states to set their abortion restrictions, curbs on affirmative action, placing checks on the administrative state, and setting an originalist test for determining the legality of gun control laws.

In the first weeks after Trump’s 2016 victory, then-Federalist Society head Leonard Leo, who is now a co-chairman for the conservative judicial group, began meeting with the president-elect to discuss possible nominees to the federal judiciary.

Trump followed Leo’s suggestion to nominate Brett Kavanaugh in 2018 after Justice Anthony Kennedy’s retirement despite controversy after multiple women levied sexual misconduct allegations against him — claims Kavanaugh vehemently denies. Republicans led by McConnell managed to confirm the justice through a 50-48 vote.

It wasn’t until the sudden death of Ginsburg in September 2020 that Trump and the GOP-led Senate had the chance to replace a Democratic-appointed justice with a Republican-appointed justice, solidifying a 6-3 supermajority on the high court. McConnell had opted not to give Garland a hearing or vote in an election year, yet he pushed forward Trump’s nominee, Amy Coney Barrett, with less than two months before the presidential election. Barrett was confirmed on Oct. 26, 2020, and the GOP lost the White House and control of the Senate in the succeeding election.

Still, Republican handling of Reid’s rule change has left Democrats to simmer over how McConnell adapted to make the federal judiciary a powerhouse of young, right-leaning nominees.

“He withheld Obama’s opportunity to fill the vacancy on the Supreme Court,” Durbin, who also chairs the Senate Judiciary Committee, said after McConnell announced his plan to step down as leader on Feb. 29. “It tipped the balance on the court, and we’re paying for it now.”

While Democrats cried foul in the process of McConnell’s calculated moves, they were powerless to reverse his decision because Republicans stuck with him despite division on other matters. One former senior Republican Senate leadership aide told the Washington Examiner that McConnell understood the need for his party to make inroads for federal lifetime appointments, just like Democrats did when they “captured the courts” more than 20 years ago.

“Most of [Democrats’] gains had been what courts did,” the aide said, noting Democrats got to a point at which they thought they could “just rest on their laurels” after achieving landmark success in the courts, including cases such as Roe v. Wade and Lawrence v. Texas.

Possible McConnell successors

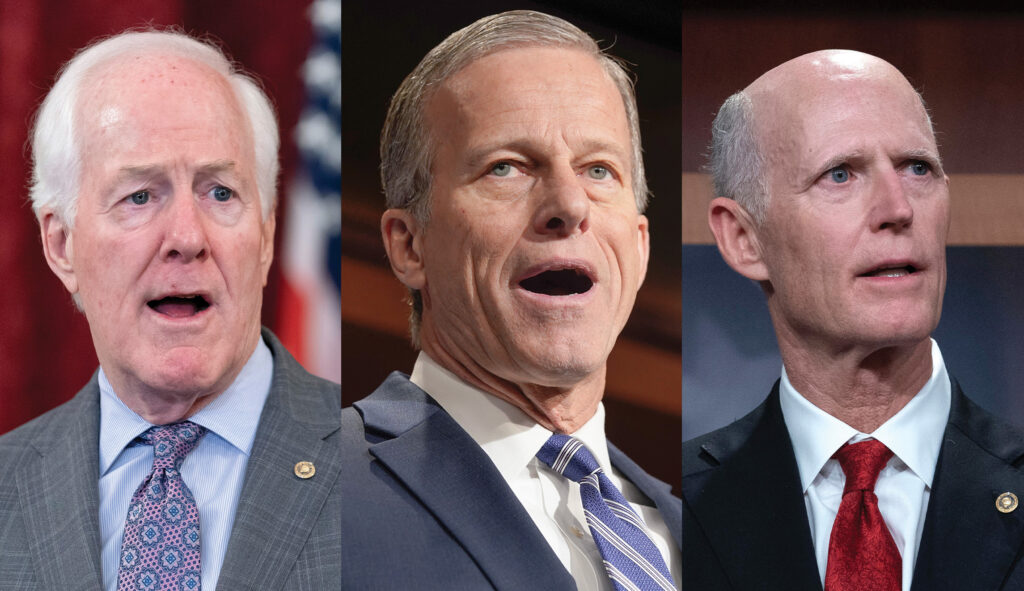

For now, the race to be McConnell’s successor is between Sen. John Cornyn (R-TX) and Senate Minority Whip John Thune (R-SD), though Sen. Rick Scott (R-FL) has also signaled interest in entering the race.

Sen. John Kennedy (R-LA), who sits on the Senate Judiciary Committee with Graham and Cornyn, commended McConnell for his leadership in a statement to the Washington Examiner, saying, “He has always backed me up on Judiciary when I stepped on someone’s toes.”

While Graham and Kennedy didn’t opine on who they’d like to see as the new leader, the latter touted McConnell’s “deep respect” for the federal judiciary, a quality that will surely be sought after by many GOP senators when it comes to voting on a successor.

In a statement to the Washington Examiner, Thune emphasized one of the Senate’s chief duties is ensuring members of the federal judiciary are qualified and “understand the limited role” it plays among the three coequal branches of power.

“I’m incredibly proud of how the Senate Republican Conference worked as a team with former President Trump to shape the federal judiciary,” Thune said. “I look forward to working with him to double down on our efforts during his next term in office.”

Senate Judiciary Committee Republicans, albeit in the minority, have played a part in keeping as many checks and balances as they can on President Joe Biden’s judicial nominees. Biden needs to secure 44 lifetime judicial confirmations in the roughly nine months left in his term to match the 234 such confirmations of Trump appointees, and he has made 23 such nominations that are in the Senate confirmation process.

Some analysts have said Cornyn may have some advantages over his likely rivals, in part because of his legal background. He even touted Trump in his announcement, writing, “I helped President Trump advance his agenda through the Senate, including passing historic tax reform and remaking our judiciary – including two Supreme Court Justices.”

But given Trump’s undying influence on the party and his role as the presumptive Republican nominee for president, whoever is the Senate’s next GOP leader will face a group divided between MAGA policies and principles and more traditional Republicans who are willing to work across the aisle.

Cornyn, in addition to waiting until the second Republican primary contest in New Hampshire to endorse Trump, was booed at a Texas Republican convention after his negotiation on bipartisan gun safety legislation following the Uvalde mass shooting. But Cornyn’s ability to raise cash and his willingness to align himself with Trump, like McConnell, could draw the former president closer to offering an endorsement for the leadership position.

CLICK HERE TO READ MORE FROM THE WASHINGTON EXAMINER

“Who knows how it all plays out, but I know that Cornyn and Thune at times have gotten a little crosswise with the former president,” said Darling, the former Senate aide. Darling added that Trump could seek to rely on his intuition for federal judicial nominees if reelected to a second term.

“Trump’s been through it once. So he doesn’t need to rely on outside organizations to tell him what to do. I think he can come up with his own list,” Darling said. “It’s possible he will be more aggressive and get even more conservative nominees than he might get from the Federalist Society.”