It’s a five-hour, 350-mile drive from Rifle, Colorado, where Rep. Lauren Boebert once owned and ran the Second Amendment-themed Shooters Grill restaurant, to the small municipality of Holyoke, in the state’s northeastern corner. Boebert is betting the political distance isn’t so vast.

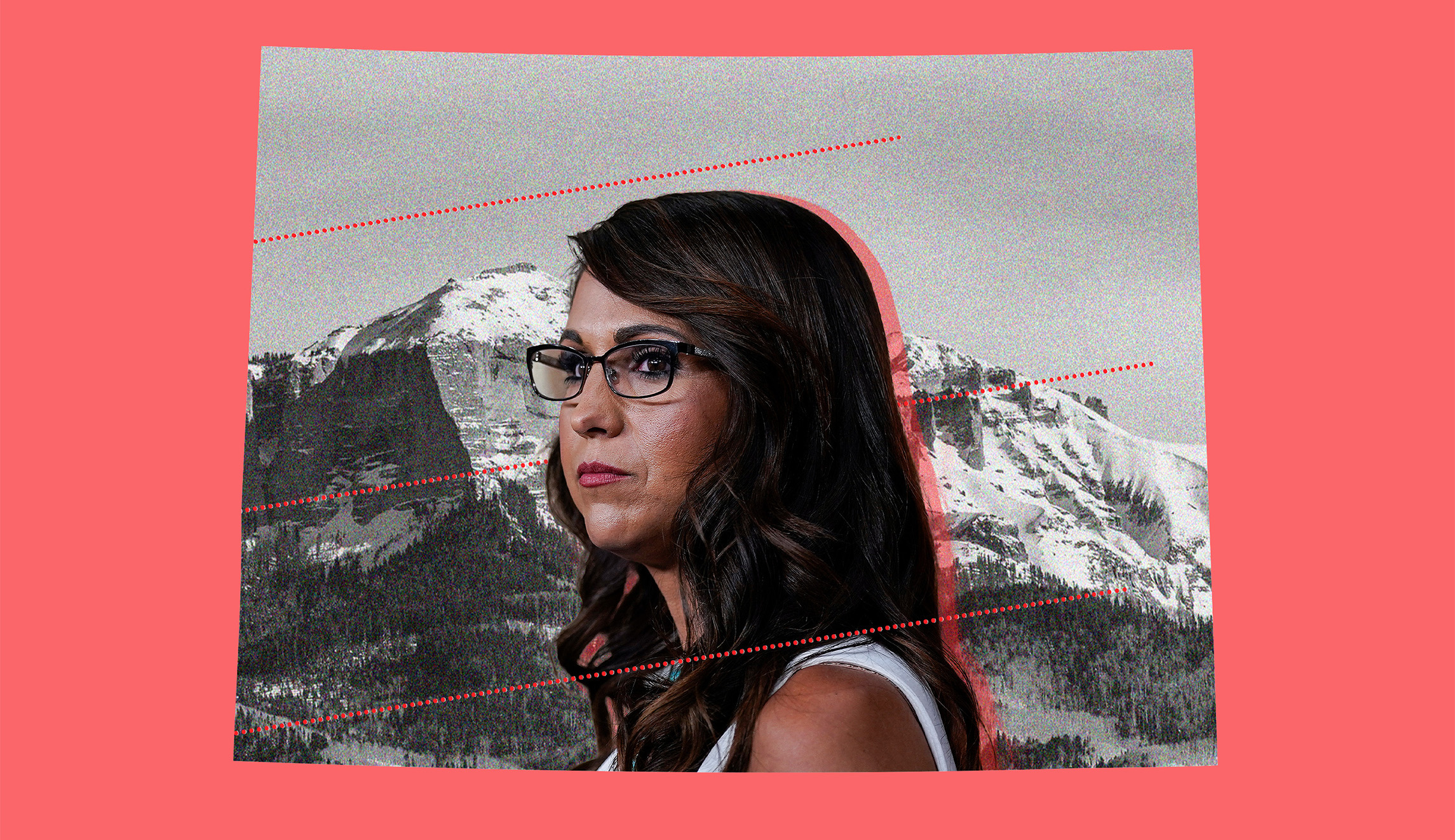

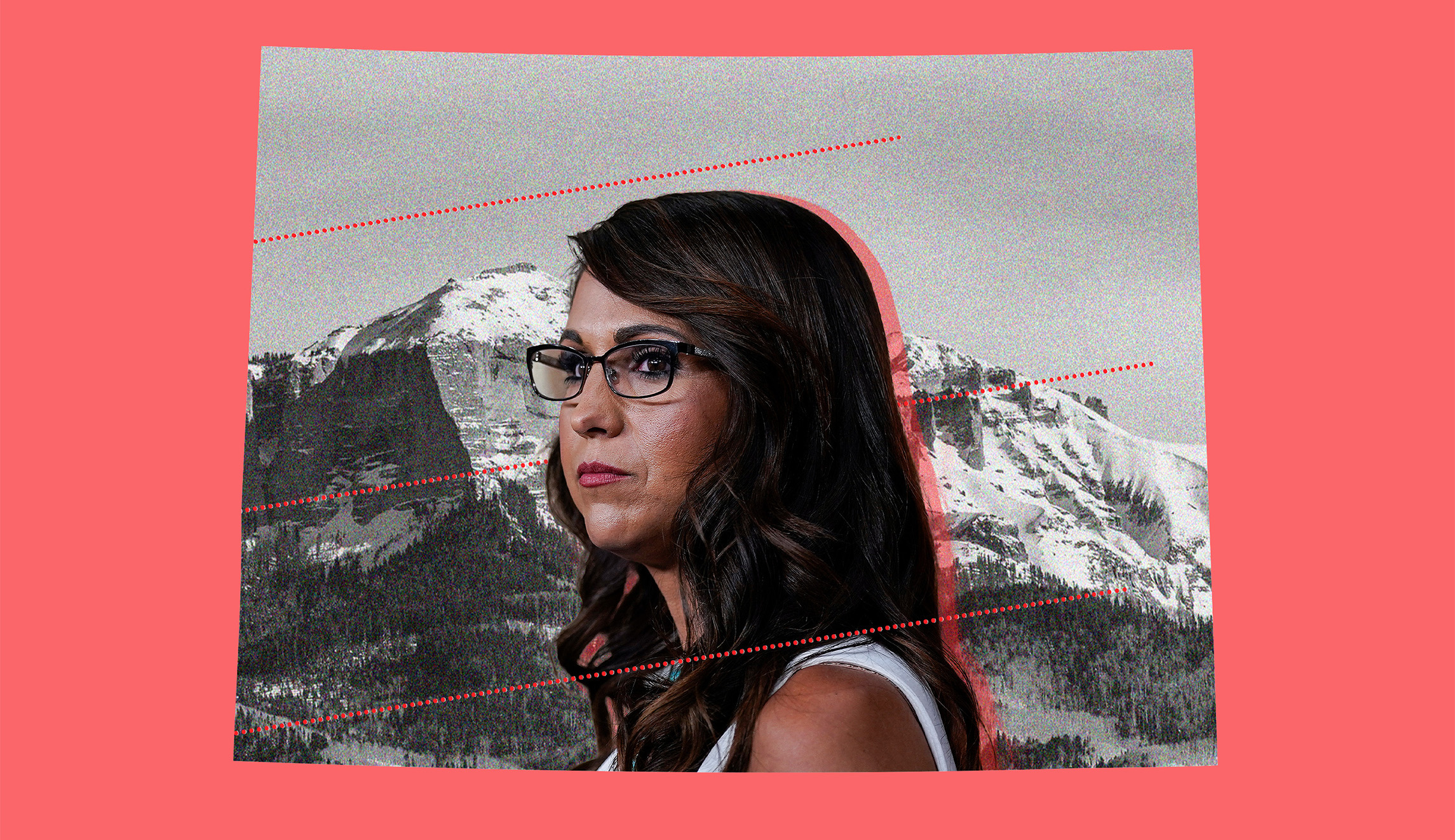

Boebert, a high-profile House Republican and one of former President Donald Trump’s staunchest defenders in Congress, is leaving the Pueblo area and Western Slope 3rd Congressional District. She’s moving clear cross-state, running for reelection in the eastern Colorado and Denver exurbs 4th Congressional District, effectively trying to trade a conservative-leaning yet increasingly purplish district straddling Colorado’s entire western state line, with Utah, for a deep-red constituency whose deep-red politics more mirror those of neighboring Kansas and Nebraska.

Boebert, first elected to the House in 2020 after upsetting a 10-year incumbent in the Republican primary, is moving after seeming to wear out her welcome in western Colorado. In 2022, she beat Democratic rival Adam Frisch 50.1% to 49.%, or 546 votes out of more than 327,000 cast. That in a district where in 2020 Trump would have beaten President Joe Biden 52.9% to 44.7%. Frisch, a businessman and former member of the Aspen City Council, is running again, with Colorado’s congressional primaries on June 25.

Boebert made a name for herself nationally soon after joining Congress three years ago. Her controversies included resisting mask and vaccine mandates in the House chamber, which earned her a $500 fine from the House Ethics Committee. She set off metal detectors at the entrance to the House floor by refusing to part with her gun, causing a dispute with Capitol Police. Boebert also amplified Trump’s baseless election fraud claims, tweeting that “today is 1776” on the day of the Jan. 6 attack on the Capitol. Democrats seethed at Boebert’s behavior and have an even longer bill of particulars about her outrages, which they deem unbecoming a member of Congress.

Yet Boebert’s political prospects took on a more dire tone after a September incident in which she was escorted out of a Denver performance of Beetlejuice for vaping, groping her companion, and generally causing a disturbance. Social media and late-night comics ran wild with jokes about Boebert’s “hands-on” brand of politics and the like.

A new constituency

The 4th Congressional District seat is open because Rep. Ken Buck (R-CO) is retiring after eight years. Voters there would have backed Trump over Biden 58% to 39.%. So, winning the Republican primary is all that matters to nab the open seat.

The next five months will test how much of a desire there is by voters for Boebert’s brand of performative politics. Several prominent Republicans also are seeking their party’s nod. That includes Mara Bailey, a former congressional aide; former state Sen. Ted Harvey; state Rep. Richard Holtorf; Weld County Councilman Trent Leisy; state House Minority Leader Mike Lynch; businessman and former congressional aide Chris Phelan; and Logan County Commissioner Jerry Sonnenberg, who previously was a member of both chambers in the state legislature.

Each rival candidate to Boebert brings his or her own MAGA-esque credentials to the Republican primary. And the bulk of them have held public office for years in the region.

As for Democrat Frisch back in the 3rd Congressional District, his candidacy could go a couple of ways. It’s still possible Frisch could win. After all, Frisch raised a ton of money, and even if his fundraising doesn’t continue at stratospheric levels now that Boebert’s out of the race, he’ll still have the necessary resources to wage a competitive race.

Moreover, while the congressional district has a distinct Republican tilt, it’s not insurmountable. The district also includes several Denver suburbs and exurbs, which are growing increasingly blue.

“Adam is running to make sure his district has real representation in Congress. We’re going to help him finish the job and put the House back to work for the American people, not political extremists,” Rep. Marie Gluesenkamp Perez (D-WA) posted on X, formerly Twitter, on Dec. 28.

And another 2024 Democratic House candidate, Will Rollins, running in the inland Southern California 41st Congressional District, told the Washington Examiner in an interview that Frisch was a model for others challenging Republican opponents. Rollins credited Frisch with coining the term “Angertainment” about right-win provocateurs in the House, such as Boebert and Reps. Marjorie Taylor Greene (R-GA) and Matt Gaetz (R-FL).

Still, Frisch could wind up like the would-be 2014 challenger to then-Rep. Michele Bachmann (R-MN). Bachmann, like Boebert, was a telegenic conservative female House member with a knack for drawing national attention. Bachmann became a Tea Party-era star about halfway through her 2007-15 House tenure as Republicans won a majority in the chamber.

But Bachmann flew too close to the sun politically. Bachmann’s Minnesota voter support wilted in the northern and western Minneapolis exurbs 6th Congressional District, which she’d first been elected to represent in 2006. Wealthy Democratic local businessman Jim Graves jumped in the 2014 race after her 2012 bid for the Republican nomination flamed out. Democrats were high on his chances — until Bachmann, facing political reality, quit the race.

That ended the raison d’être for Graves’s candidacy. His support from House Democrats’ campaign arm dried up. He was gone by the end of May 2013. Tom Emmer went on to claim the seat, and the nearly 10-year Republican congressman now is the House majority whip.

Frisch looks likely to finish out his race over the next 9 1/2 months. Republican candidates in the 3rd Congressional District include state Rep. Ron Hanks and attorney Jeff Hurd, who had jumped into the nomination fight even before Boebert picked up and left the district.

Incumbent district switchers

Boebert’s move is a rare example of an incumbent lawmaker moving clear across the state to run in a different district. Some House incumbents have run elsewhere in their regions when new maps came into being due to redistricting, usually in years starting with “2” after once-in-a-decade Census Bureau figures are released.

Rep. Pete Sessions (R-TX) did so ahead of the 2002 election cycle. After the 2000 census made the then-5th Congressional District, in suburban Dallas, slightly more Democratic, he moved to the newly created 32nd District. He easily prevailed in that new district, in redder parts of the Dallas area, and has spent most of the rest of the past 20 years as a House member.

The closest analogy to Boebert’s move is Rep. Mario Diaz-Balart (R-FL), first elected in 2002.

In February 2010, he jumped to a neighboring South Florida district being vacated by his brother, retiring Rep. Lincoln Diaz-Balart. Unlike Rep. Mario Diaz-Balart’s old 25th Congressional District, the 21st Congressional District had long been considered the Miami area’s most Republican seat. No other party even fielded a candidate when filing closed on April 30, 2010, handing Diaz-Balart the seat. He hasn’t had a tough race since and now is the most senior member of Florida’s congressional delegation.

House members with two separate stints in office sometimes represent districts hundreds of miles apart. Take former Rep. Dan Lungren (R-CA), who represented a Long Beach-based district in Southern California from 1979-89. After eight years as attorney general and being the losing 1998 Republican gubernatorial nominee, Lungren made a political comeback in a Sacramento-area House district that’s usually a six-hour or so drive from his old home. Lungren said those years in state government, as California’s top law enforcement officer, made him a Sacramento-region resident, and he won an open House seat in 2004.

But like much of California, the district was becoming bluer, and Lungren lost reelection in 2012. Yet he had set an example, followed by a longer period of electoral success from Rep. Tom McClintock (R-CA). Elected to the California State Assembly at age 26 in 1982, representing a then-conservative-leaning swath of territory northwest of Los Angeles, primarily in Ventura County, McClintock became a prominent conservative in California.

McClintock had a second Assembly stint in the late 1990s and moved up to the state Senate for eight years. In between, he lost a series of races, first for the House, in 1992, followed by statewide bids for controller (twice), lieutenant governor, and in the 2003 California gubernatorial recall election.

But a new political opportunity arose in 2008, when the incumbent Republican House member in a northeastern California district retired after 18 years. McClintock ran for, and won, the seat, about 300 miles north of the district McClintock represented in the state Senate. Today, McClintock represents the upper Central Valley and Sierra Nevada foothills 5th Congressional District.

Further up the West Coast, Gov. Jay Inslee (D-WA) once turned electoral defeat into a chance at starting over politically. As a state representative in 1992, Inslee won the then-4th Congressional District, based in the central-eastern part of the state. But he lost reelection in the 1994 “Republican Revolution” after a single, two-year term.

So, Inslee moved west to the Seattle area, nearly 150 miles from his home base in the city of Yakima. Inslee ran a much bluer district and beat a Republican incumbent. Inslee easily held the seat until resigning from the House seven months before the 2012 Washington gubernatorial election. Inslee won easily and is set to retire from the governorship after the 2024 elections.