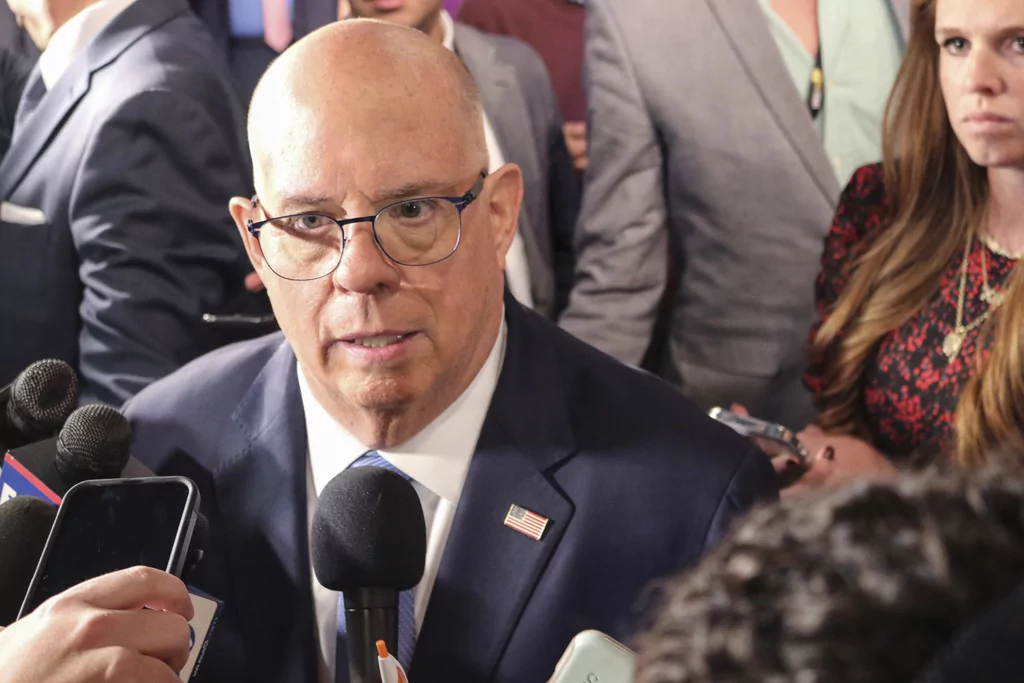

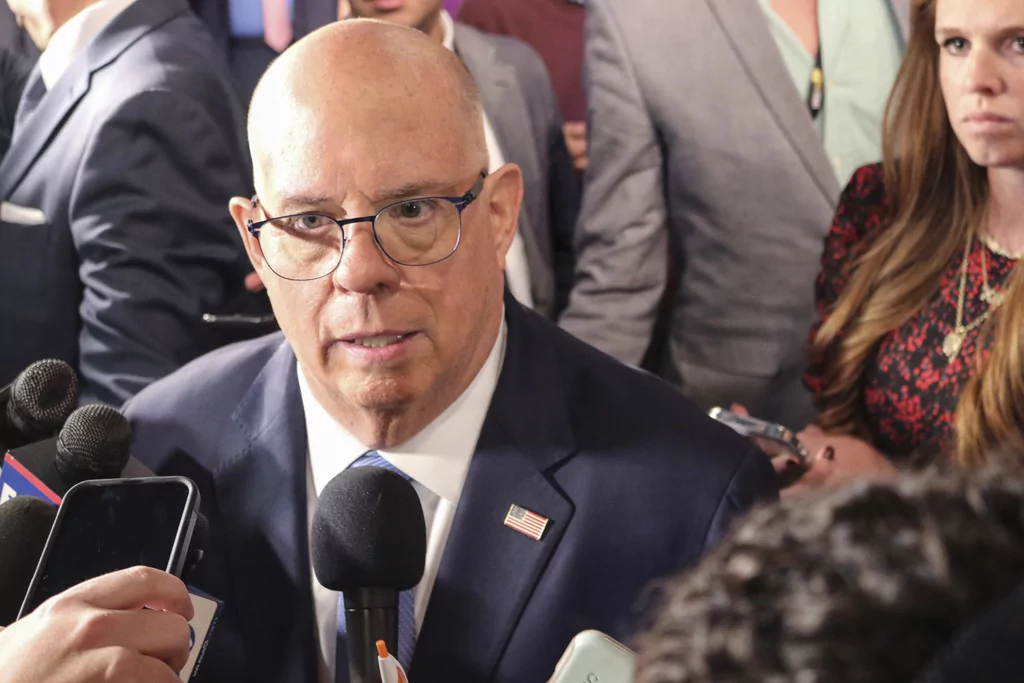

Former Maryland Gov. Larry Hogan is being honest with voters. The Republican isn’t winning over Democrats on his run for the state’s open Senate seat the same way he did when he cruised to election and reelection as one of the country’s most popular governors.

Democrats in blue states are consistently happy to hand the reins of state government over to Republicans with their heads for balanced budgets and centrist approaches to governance. But the Senate and the White House are different matters.

Winning as a Republican in deep-blue Maryland is no mean feat, but Hogan did it twice — once by a slim margin and then without breaking a sweat four years later. Now he’s finding that even though Maryland voters didn’t have a problem sending him to the governor’s mansion regardless of the letter that sat next to his name on the ballot, picking a senator to represent them a couple of miles south in the Capitol is a whole different ballgame.

“The last two elections, I think I got about a third of the Democrats,” Hogan said earlier this month. “We’re not quite there. I think we’re in the high 20s at this point.”

On the one hand, it’s surprising Hogan is struggling to tell voters who happily went to the polls for him in 2018 that they should do so again. Despite saying and doing all the right things, the popular two-term governor with high name recognition and a record of working with Democrats is struggling to remain competitive with Prince George’s County Executive Angela Alsobrooks.

Moderation and counterweights

There was a time not long ago when it was regular, if not common, to see states with deep ideological lines leaning in one direction abandon partisanship and enlist a leader from the out-party to lead their state. And the picks were overwhelmingly popular.

As recently as 2019, Hogan was in a group of Republican governors leading blue states that were four of the five most popular leaders in the country. Joining Hogan were Massachusetts Gov. Charlie Baker, New Hampshire Gov. Chris Sununu, and Vermont Gov. Phil Scott.

These centrist heavyweights didn’t win over their severely partisan states by abandoning conservative principles either. All four of them did tout more permissive rules surrounding abortion and LGBT rights than the standard GOP representative or senator in Washington, but none of the men could be accused of acting as Democrats in Republican clothing.

Hogan described his job as governor as being a “goalie” who was put in place to stop Democrats from running roughshod over the state with every idea the legislature came up with.

“Right now, it’s an open net. It’s just every single crazy thing that they want to get in just gets done,” Hogan said when he was first elected. “One major thing we can do is play goalie. There’s not going to be a huge offensive game. We’re going to be able to score here and there, and we’re going to stop bad things from happening and continuing to drive our state into the ground.”

Hogan was successful in reining in his legislature’s spending habits a bit. He balanced the state’s budget and cut tolls, though he ran into the brick wall of a Democratic supermajority overriding his veto on a bill that raised the state’s minimum wage to $15 an hour.

Scott had similar success in Vermont. He stopped the legislature from raising property taxes and raising the minimum wage to $15. His focus on responsible spending consistently won him larger and larger margins of victory in the same state Sen. Bernie Sanders (I-VT) calls home.

“Scott’s big word is ‘affordability,’” Philip Baruth, a state senator who affiliates with both the Democratic and Progressive parties, said in 2021. “He’s generally pro-economic development and low-tax and doesn’t like things he views as not in the government’s purview or as costing too much, like universal healthcare.”

Massachusetts might be the ultimate case of Democratic voters turning to Republicans to help steer their ships of state. Sen. Mitt Romney (R-UT) was a successful and popular governor there before running for president and moving across the country and landing in Utah.

When Baker was at the helm, he was less of a fiscal hawk than Hogan or Scott. But he also vetoed a bill that would have allowed illegal immigrants to obtain state-issued driver’s licenses.

Even voters in states that consistently lean to the left are eager to have someone at the head of the government who will stop to pump the brakes occasionally, Alan Abramowitz, Alben W. Barkley professor emeritus at Emory University, told the Washington Examiner.

“You can also run as a counterweight to the majority as a governor,” Abramowitz said. “They will kind of act as limits on the excesses of the majority of the major party. To have some degree of party competition, which voters might see as a good thing when it comes to control of state government.”

All politics is national

Competition and counterweights in Washington are different though. The margins of power are razor thin, and the “rebel” governors willing to part ways with their party for the sake of running their state as they see fit are less likely to buck leaders in the House and Senate.

Hogan is no ally of Trump, but he could wind up as the tipping point in the Senate. Maryland voters who want to see Vice President Kamala Harris promoted so she can continue splashing out on green energy subsidies and loose immigration regulations don’t want to see a Republican-controlled Senate thwarting her agenda.

“When you vote for a candidate for House or Senate, it’s no longer primarily about who you want to represent your state or district, who you think could do a better job, who you like better to be your own representative,” Abramowitz said. “It’s about which party do you want to be in control of that chamber.”

“It’s about the national issues that are affected by that.”

National priorities, and how the country pays for them, are problems that can be dealt with at arm’s length. Because the responsibility of hashing out national issues is shared among all the states, and the bill is covered by all taxpayers, it’s easy for Democrats who want smaller tabs and more focused governance at home to support massive government projects at the national level. Balancing a budget is more important to taxpayers when they can track their taxes going to profligate spending in their backyard. Voters in Maryland, Vermont, and Massachusetts understand they only foot a fraction of the ballooning national debt.

High levels of partisanship that have resulted in microscopic minorities in both chambers and the proliferation of presidents ruling via executive order feed into the cycle of not trusting centrist governors to continue their work away from the state.

“You’re talking about two different constituencies when you’re talking about the governor’s office or the president’s office,” Patricia Crouse, an adjunct professor of political science at the University of New Haven, told the Washington Examiner. “But trying to run for the Senate is very different because then you have to appeal to whatever constituency is in your particular district, and that doesn’t necessarily coincide with the constituency that’s electing you.”

Crouse said she doesn’t believe the country is as polarized as it seems at the state level, but it does “rise to the top” when it comes to House, Senate, and presidential elections.

“People at the state level are more tied to issues. People at the national level are more tied to party,” she said. “I don’t think we view national politics through the same lens that we do state and local politics.”

Those Democratic outliers

Split-ticket governors don’t break just one way. There have been a handful of Democratic governors elected and reelected in deep-red states, though the circumstances attending their rise have been different than their GOP counterparts.

The overwhelming pattern is that races for governor move in the same direction as national sentiment, Abramowitz said. But there are outliers.

Abramowitz mentioned Gov. Andy Beshear (D-KY) specifically, noting his father was a well-known governor himself and the Beshear name carries a lot of weight in the state.

Kentucky has voted for the Republican nominee for president almost without fail since 1980. The state swung in Bill Clinton’s favor during both of his runs, and Jimmy Carter won the state in 1976. But Beshear had a familiar name and a historically unpopular GOP opponent when he first ran for governor in 2019.

He snuck past then-Gov. Matt Bevin, a Republican, by 5,000 votes that year. But with the winds of incumbency at his back, he dispatched rising GOP star and state Attorney General Daniel Cameron with ease two years later.

Former Louisiana Gov. John Bel Edwards had a similar path to winning his red state’s top job as a Democrat. Edwards didn’t have to run against the unpopular incumbent Gov. Bobby Jindal, who was term-limited, all he had to do was be someone other than Jindal. He could offer a clean break with the policies and politics of his predecessor at a time when the electorate was looking for anything new.

When Edwards ran up against the state’s term limits law, voters pivoted away from his party and turned to Gov. Jeff Landry (R-LA), who ran away with the contest, crushing Democrat Shawn Wilson by 270,000 votes.

Balancing dominance

Voter priorities fluctuate from year to year and contest to contest. Entrenching their preferred party’s control in Washington, particularly in the White House, drives whether states are viewed as “red” or “blue.” But the immediate effects state legislatures have on the lives of voters forces sober-minded constituents to reconsider how much power they want to hand over to elected officials.

Handing power to Republican governors like Hogan is an example of states “trying to make sure that one party does not have complete control over how policies are getting made,” Crouse said.

CLICK HERE TO READ MORE FROM THE WASHINGTON EXAMINER

“I think that’s a conscious effort by voters in those states to try and make sure that they’re not creating a system that’s just going to be some rubber stamp for policy,” she said. “They don’t want someone in office who’s just gonna create policies that benefit one party or the other.”

If voters are concerned about government intrusion and single-party rule, they might consider the checks and balances blue states have placed on themselves by putting Republicans in a position to step back and slow down the wheel of Democratic government.