Gov. Gavin Newsom (D-CA) partnered with a Chinese Communist Party-tied businessman – allegedly connected to the triads – on an endeavor that brought Chinese mafia-linked businesses to California’s Bay Area when Newsom served as San Francisco’s mayor, Peter Schweizer reveals in his new book Blood Money: Why the Powerful Turn a Blind Eye While China Kills Americans.

Schweizer reveals in Blood Money that Newsom has had links to Chinese organized crime through his connections to known triad members and that these connections go beyond the ChinaSF initiative that Newsom launched in 2008 to bring Chinese businesses to San Francisco. Schweizer also argues that Newsom has skirted addressing China’s role in the fentanyl trade that has killed so many Californians.

Schweizer, a New York Times best-selling author whose investigative work has led to bombshell revelations of corruption among America’s elite, highlights Newsom’s relationship with Chinese businessman Vincent Lo, who served as the cochairman of ChinaSF and the president of the Council for the Promotion and Development of Yangtze.

Schweizer describes ChinaSF as “an ambitious effort to make the Bay Area the ‘premiere [sic] U.S. gateway for Chinese companies expanding into the North American market.’”

Schweizer writes in Blood Money:

ChinaSF was highly favorable to the Chinese entities involved: any investment they made in an American company would grant them intellectual property rights in China for the technology developed. It “would involve U.S. companies handing over their secret formulas.” But many of the Chinese companies and businessmen that were involved in ChinaSF and benefited from the program had ties to Chinese organized crime.

Newsom’s ChinaSF partner Vincent Lo has ties to the Chinese Communist Party (CCP), as well as alleged ties to the triads, according to Blood Money.

“In the 1990s, Lo’s company reportedly hired triad members to provide ‘canteen and security services’ on his building sites on construction projects around Hong Kong. His company first confirmed the practice, but then Lo denied it,” Schweizer writes. “Lo also backed a Hong Kong politician whose associates were accused of soliciting support from triad members. At the same time, a prominent businessman accused Lo’s companies of ‘sending armed thugs’ likely linked to Chinese triads to forcibly take over his luxury villa complex in suburban Beijing. Lo’s company denies the claim.”

Moreover, Lo is a Real Estate Developers of Association of Hong Kong board member along with his brother, and Schweizer notes that the association’s “leadership is populated with developers linked to the triads.”

“Why did Newsom partner with an individual with all these alleged triad connections?” Schweizer writes. “Lo and his family secured large deals in the Bay Area with help from Newsom’s ChinaSF. Lo and his business associates acquired the iconic Bank of America Center in San Francisco. ChinaSF championed development projects carried out by Lo’s family, including the 555 Howard Street project in the Bay Area, which is tied to the California High-Speed Rail project long championed by Governor Newsom.”

ChinaSF also benefited other businessmen who have ties to the triads, according to Schweizer:

In 2010, Newsom announced that he was bringing the headquarters of a Chinese energy company called GCL-Poly to San Francisco. The company was partly owned by a subsidiary of China Poly Group, a company with “intimate ties” to the Chinese military. In fact, in the 1990s, the company had been implicated in a plan to smuggle thousands of fully automatic machine guns into the United States and has been tied to “sketchy dealings with third-world dictators and arms traders” around the world. China Poly is also said to work “hand and glove” with Chinese organized crime figures: according to one report, triad-linked Stanley Ho once “spent millions” to acquire an object of tremendous propaganda value for the company. Why would Newsom’s ChinaSF green-light such a company’s moving into San Francisco?

Trina Solar Company was another energy company that Newsom announced would be coming to the Bay Area, and it would later be “embroiled in controversy” surrounding an American company’s intellectual property, according to Blood Money. A CEO for one of Trinar Solar Company’s American competitors levied allegations that “it was likely receiving support from the People’s Liberation Army via hackers who were stealing intellectual property from competitors and giving it to the company.”

A GCL-Poly Energy Holdings Ltd. facility in Changji, Xinjiang province, China, on March 2, 2021. Factories in Xinjiang produce nearly half the world’s polysilicon supply. (Colum Murphy/Bloomberg via Getty Images)

The Trina Solar Ltd. headquarters in Changzhou, Jiangsu Province, China, on April 24, 2015. Trina Solar is the world’s biggest solar manufacturer. (Tomohiro Ohsumi/Bloomberg via Getty Images)

Additionally, Newsom touted the arrival of offices for the Chinese-government-controlled newspaper China Daily in San Francisco through ChinaSF.

Notably, the ChinaSF initiative was being launched at the same time then-mayor Newsom ran a “fake-out” in San Francisco during the passing of the torch relay in the lead-up to the 2008 Beijing Olympics after protests in major European cities had “deeply embarrassed” China, Schweizer explains.

“Earlier torch relays in London and Paris had been met by human rights protestors, which had deeply embarrassed Beijing. So Newsom executed an intricate ‘fake-out,’ changing the torch relay route at the last minute, leaving thousands of protestors and supporters at one end of San Francisco while the torch passed through the other side of town,” Schweizer writes. “The protestors were furious, as were Bay Area leaders from Newsom’s own political party.”

Pro-China spectators who had been waiting since as early as 6 am along the intended route of the Olympic Torch relay watch as a phalanx of police walk to take up positions along the originally planned route on April 9, 2008, in San Francisco, California. The torch was diverted shortly after being lit and never took this route. (ROBYN BECK/AFP via Getty Images)

The first torch runner, Chinese Olympic swimmer Lin Li (left) holds the flame and waves at the start of the Olympic Torch relay on April 9, 2008, in San Francisco, California. Hundreds of baton-wielding police herded the Olympic torch through San Francisco as organizers switched the relay course to avoid people protesting the Chinese Communist regime’s human rights abuses, as happened during the Beijing Olympic’s torch relays through Paris and London earlier. (ROBYN BECK/AFP via Getty Images)

Protestors scaled the Golden Gate Bridge to hang “Free Tibet” banners on April 7, 2008, in San Francisco, California, in anticipation of the Beijing Olympic’s torch relay through San Francisco that day. (Justin Sullivan/Getty Images)

Two sailboats with pro-Tibet banners pass police and Coast Guard boats patrolling the harbor before the start of the Olympic Torch relay on April 9, 2008 in San Francisco, California. (ROBYN BECK/AFP via Getty Images)

Tibetan activists protest before before the 2008 Beijing Olympic torch relay in San Francisco, California, on April 9, 2008. Police on bicycles, in boats and in running shoes deployed along San Francisco’s waterfront as thousands of protesters gathered for a shortened and re-routed relay of the 2008 Olympic torch in San Francisco, which was the only North American stop for the Beijing Olympic’s torch relay. (Kimberly White/Bloomberg via Getty Images)

Thousands of protestors march up San Francisco’s Embarcadero to the Ferry Building were they hoped to greet the Beijing Olympic Torch relay on April 9, 2008. But San Francisco Mayor Gavin Newsom re-routed the torch relay at the last minute to avoid embarrassing the Chinese Communist regime. (LANCE IVERSEN/San Francisco Chronicle via Getty Images)

San Francisco Mayor Gavin Newsom’s police officer drag to the ground a pro-Tibetan demonstrator protesting China’s human rights abuses during the Beijing Olympic Torch relay in San Francisco, California, on April 9, 2008. (Ryan Anson/AFP via Getty Images)

San Francisco Mayor Gavin Newsom’s police officers tackle a pro-Tibetan demonstrator protesting China’s human rights abuses during the Beijing Olympic Torch relay in San Francisco, California, on April 9, 2008. (Ryan Anson/AFP via Getty Images)

Newsom’s links to triad members also went beyond the ChinaSF endeavor, Schweizer writes:

Mayor Newsom worked with a San Francisco businessman named Allen Leung and reappointed him as chairman of the Chinatown Economic Development Group. But Leung was no ordinary businessman; he was the dragonhead of the “ominous” Chee (variously “Ghee” or “Gee”) Kung Tong, “transpacific incarnations of criminal Triad gangs originating in China.” Members of his gang were involved in the drug trade. Leung was brutally murdered in 2006.

Then there is Raymond “Shrimp Boy” Chow, “Leung’s successor,” with whom “Newsom also had a fishy history,” according to Schweizer. The Blood Money author explains that Shrimp Boy was “an organized crime leader in San Francisco’s Chinatown” and served multiple prison sentences in the 1970s and 1980s for armed robbery and assault with a deadly weapon, respectively. After that, “he worked for leaders in the Wo Hop triad” and was incarcerated again in the 1990s on firearms charges, Schweizer reports. Shrimp Boy cooperated with the Department of Justice, leading to his early release.

FBI agents lock up the door of the Ghee Kung Tong Free Mason building in San Francisco, California, on March 26, 2014. This was one of many locations raided by the FBI as part of a widespread federal criminal complaint filed on March 24 involving State Sen. Leland Yee and 25 others including Raymond “Shrimp Boy” Chow, the leader of the Ghee Kung Tong organization. (Laura A. Oda/MediaNews Group/East Bay Times via Getty Images)

FBI agents raid the Ghee Kung Tong Free Mason building in San Francisco, California, on March 26, 2014, as part of a massive investigation of Raymond “Shrimp Boy” Chow’s Ghee Kung Tong organization. (Laura A. Oda/MediaNews Group/East Bay Times via Getty Images)

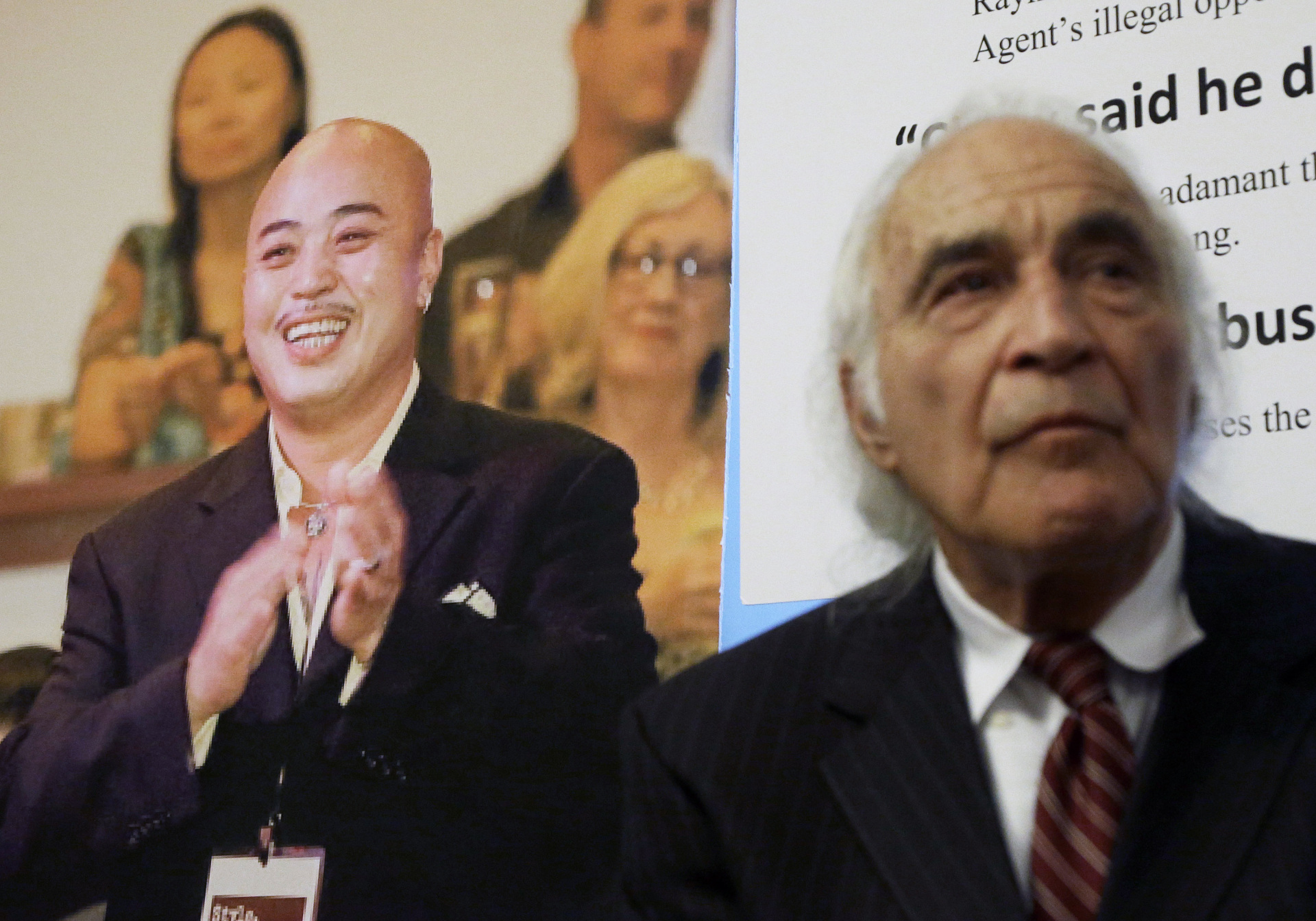

Tony Serra, right, former attorney for Raymond Chow, known as “Shrimp Boy,” pictured at left, listens to speakers at a news conference in San Francisco on April 10, 2014. A federal judge on Aug. 4, 2016, sentenced the San Francisco Chinatown gang leader known as “Shrimp Boy” to two life sentences, one for killing a rival, in a wide-ranging organized crime investigation that also brought down a state senator. (AP Photo/Jeff Chiu)

“Controversy ensued when Shrimp Boy took control of an organization that the mayor’s office was funding. Public outrage in the Asian community in San Francisco led Newsom to cancel the contract,” Schweizer writes. “The grant was withdrawn, but there seemed to be no animus with the mayor. Chow later posted a photo of himself with then lieutenant governor Gavin Newsom on his Facebook page.”

While Newsom was still lieutenant governor in 2016, Shrimp Boy, who was a “dragonhead” of the Chee Kung Tong himself, landed in severe legal trouble that lead to a murder conviction. Schweizer writes:

In 2016, Shrimp Boy was charged with a total of 162 counts of racketeering, aiding and abet- ting the laundering of drug money, and other offenses and was found guilty of murder. Among those crimes was his apparent involvement in the killing of Leung.

Shrimp Boy’s lawyers argued that the prosecutor in his case, who had been appointed by Newsom, culled “political figures out of the prosecution.” Those who skirted criminal charges, according to the lawyers, included individuals “appointed, connected, extremely closely associated with” Gavin Newsom and other political elites.

One of Shrimp Boy’s collaborators was a man named Keith Jackson, who would eventually face a murder-for-hire charge that was dropped when he took a plea deal, according to Blood Money.

Newsom appointed Jackson to his transition team in 2003, when Newsom was San Francisco’s mayor-elect. Jackson was described as “a fixture in the hallways of City Hall” when Newsom was mayor, Schweizer notes. Laurence Pelosi, Newsom’s cousin, even hired Jackson as a consultant for a large real estate project that was important to Newsom, according to Schweizer.

Shrimp Boy partnered with Jackson because he held “a lot of political influence and can do ‘inside deals’ with the City,” but Jackson also “had a very dark side,” according to Blood Money.

“While the FBI was investigating Shrimp Boy, its agents were introduced to Jackson, who claimed that his son ran a $50,000-a-week drug business,” Schweizer writes. “Jackson was later charged in a murder-for-hire scheme and a gunrunning deal involving Shrimp Boy and the Chinese triads. Those charges were dropped as part of a plea agreement.”

Blood Money also dives deeply into Newsom’s posture toward China as governor and his reluctance “to support even rudimentary initiatives designed to contain China’s activities in California.”

For example, Blood Money points to a bipartisan bill that Newsom ultimately vetoed in 2022, which would have halted the sales of the state’s agricultural land to foreign governments. China was the “primary focus” of the bill.

“Perhaps part of Newsom’s motive over the years has been financial,” Schweizer contends.

“He sells his wines in both mainland China and CCP-controlled Hong Kong,” Schweizer writes. “In recent years his wife has been a shareholder in several Chinese companies, to the tune of potentially hundreds of thousands of dollars.”

Meanwhile, Newsom does not appear “remotely interested” in holding China accountable for its role in the global fentanyl trade, Schweizer points out.

A homeless man is seen on a sidewalk as San Francisco fights with fentanyl problems in San Francisco, California, on February 26, 2024. (Tayfun Coskun/Anadolu via Getty Images)

A homeless man and his dog seen on a sidewalk as the city fighting with fentanyl problems in San Francisco, California, on February 26, 2024. (Tayfun Coskun/Anadolu via Getty Images)

A homeless man is seen on a sidewalk as the city fighting with fentanyl problems in San Francisco, California, on February 26, 2024. (Tayfun Coskun/Anadolu via Getty Images)

Homeless people are seen as the city fights with fentanyl problems in San Francisco, California, on February 26, 2024. (Tayfun Coskun/Anadolu via Getty Images)

“A broad national conversation dealing with Chinese organized crime, which is intimately involved in the drug trade, would raise uncomfortable questions for Newsom. And politicians like to avoid discomfort,” he writes in Blood Money.

For instance, Newsom unveiled a vision to address the fentanyl crisis in March 2023 that failed to include measures to hold the CCP accountable for the drug trade it is so heavily involved in.

“The strategy included elements such as deploying the National Guard to seize fentanyl supplies, conducting overdose prevention efforts, raising awareness about the dangers of drugs, and holding the ‘opioid pharmaceutical industry accountable,’” Blood Money states. “Somehow Newsom’s comprehensive plan overlooked holding Beijing accountable for its involvement in every step of this scourge.”

Months later, in October 2023, Newsom trekked to China for an eight-day, six-city tour organized by the Chinese People’s Association for Friendship with Foreign Countries rather than the United States because Newsom is only a state official, not a federal official. Schweizer highlights that the Chinese People’s Association for Friendship with Foreign Countries is affiliated with Chinese intelligence.

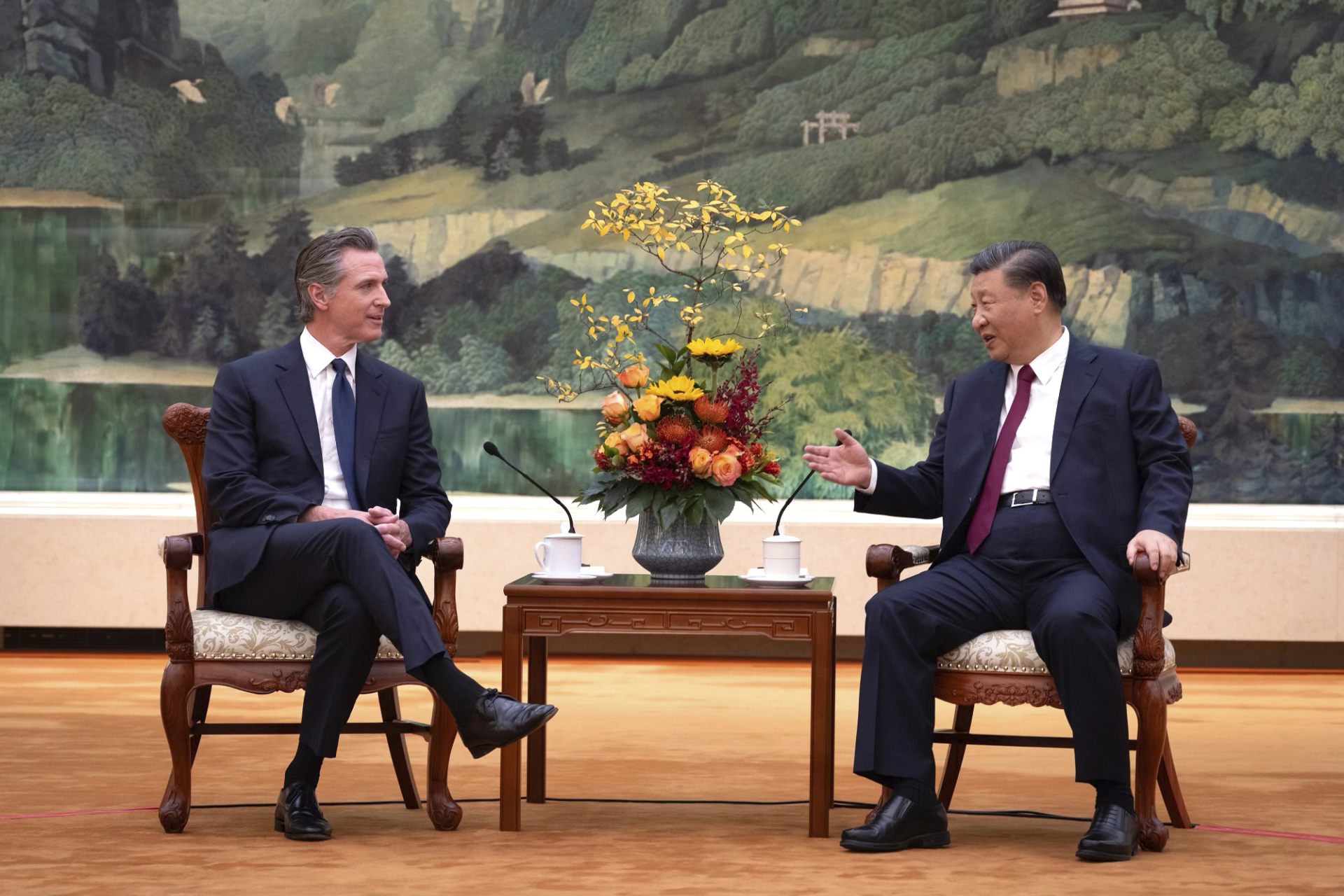

Newsom received “superlative treatment” from Beijing during the trip, according to Blood Money, evidenced by his meeting with Chinese Communist Leader Xi Jinping in the Great Hall of the People, the optics of which were starkly different from Secretary of State Anthony Blinken’s visit months before.

California Gov. Gavin Newsom walks up a section of the Great Wall on the outskirts of Beijing, China, on Oct. 26, 2023. (AP Photo/Ng Han Guan, File)

California Gov. Gavin Newsom, left, meets with Chinese Communist Party Leader Xi Jinping at the Great Hall of the People in Beijing on October 25, 2023. (Office of the Governor of California via AP)

“In an unusual move, Newsom was allowed to sit side-by-side with the Chinese leader, a sign of respect. When US Secretary of State Tony Blinken had visited earlier in the year, Blinken sat opposite Chinese officials while Xi was in the center—a position of superiority,” Schweizer writes.

A Chinese writer described the Newsom meeting as a well-intended gesture to the United States. However, it was also seen as China having a “long-term investment” in the governor, Schweizer notes, directly quoting the writer.

American media was shut out from the meeting, and Newsom completed his visit without publicly criticizing Beijing. He did, however, call on Americans “to tone down their criticisms of China,” Blood Money notes. However, Newsom’s office claimed that he did confronted Xi about precursor chemicals used in synthesizing fentanyl.

“Newsom’s office says that he brought up the subject of fentanyl with Xi in the context of ‘China’s role in combating the transnational shipping of precursor chemicals,’ implying the shipments were somehow occurring independent of the Chinese government,” Schweizer notes. “Hong Kong media wrote that Newsom ‘mentioned the fentanyl crisis in the United States’ to Xi but did not elaborate.”

Newsom would later state that his conversations with Xi around fentanyl were “honest,” but he caveating this by adding that “no fingers were being pointed.”

“For Newsom, it appears that honestly addressing the fentanyl crisis by dealing with China’s central role in the crisis might disrupt his political and financial security,” Schweizer concludes.

Blood Money, published by Harper-Collins, is available now. Schweizer, a senior contributor to Breitbart News and the president of the Government Accountability Institute (GAI), is the best-selling author of Profiles in Corruption, Clinton Cash, Secret Empires, and Red-Handed.