Fed Confidential: Secret Memo from the 1973 Debt Ceiling Fight Reveals the Fed’s Failsafe

A formerly-confidential memo from half a century ago suggests that the Federal Reserve may be able to play a bigger role than thought in easing the burden on the U.S. Treasury should the White House and Congress fail to agree to raise or suspend the debt ceiling before the government runs out of borrowing room this summer.

The memo stems from a fight over the debt ceiling in 1973 that has echoes in the debates over the debt ceiling of 2011 and today. The White House in 1973 was seeking a clean bill that would raise the debt ceiling and allow the Treasury to continue to borrow money. The government was divided, however, and the opposing party that controlled Congress sought to attach the debt ceiling legislation to another bill that contained provisions opposed by the president and his party.

Back to the Future: How Congressional Brinksmanship Held the Debt Hostage to a Liberal Agenda

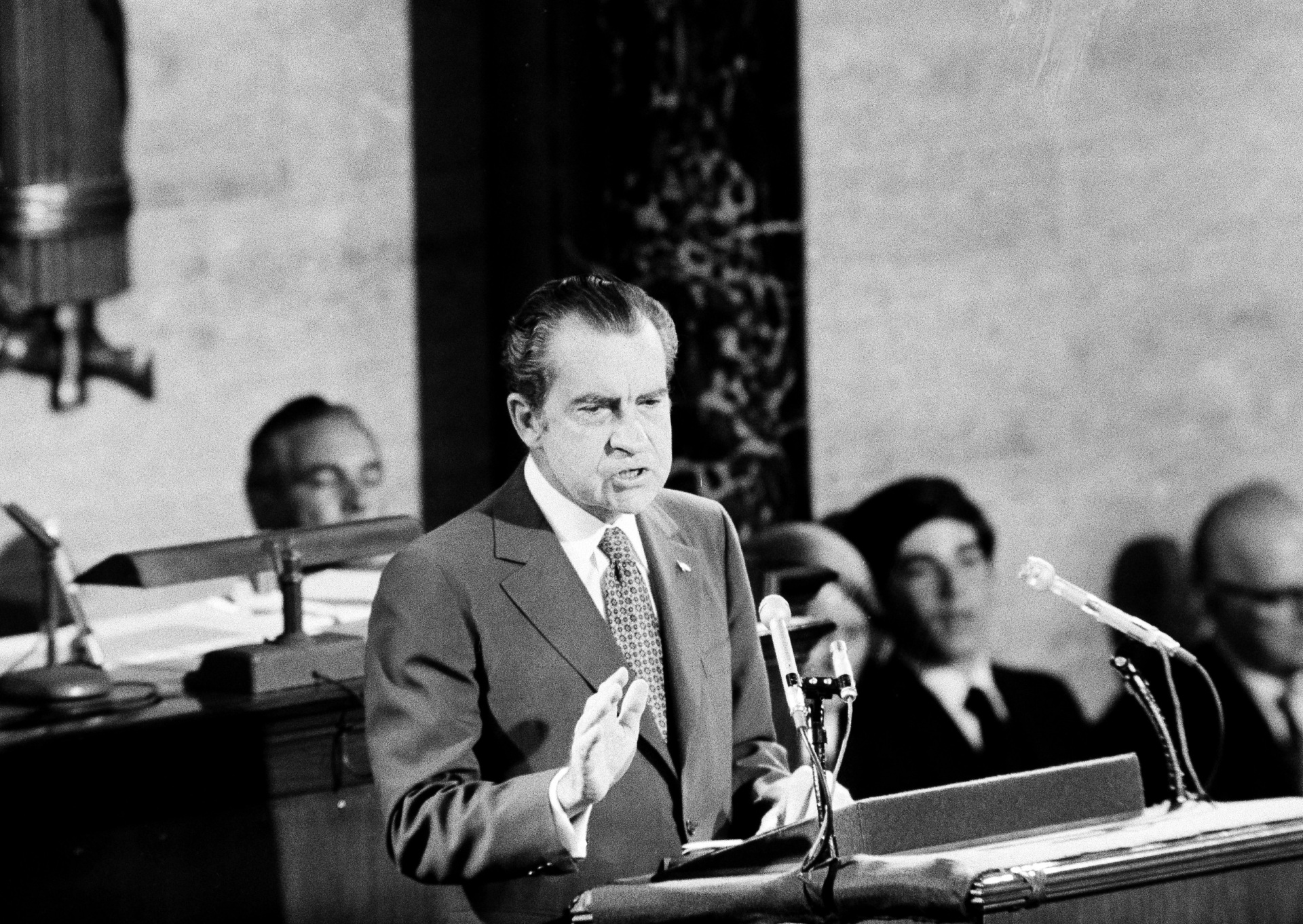

Of course, the party lines were reversed. The President was Republican Richard Nixon. Both the House and the Senate had Democrat majorities. The bill the liberals in both the Democratic and Republican parties sought to attach to the debt ceiling increase would have financed federal election campaigns with public funds. It was opposed by conservative Republicans and Democrats on Capitol Hill, as well as by the Nixon administration.

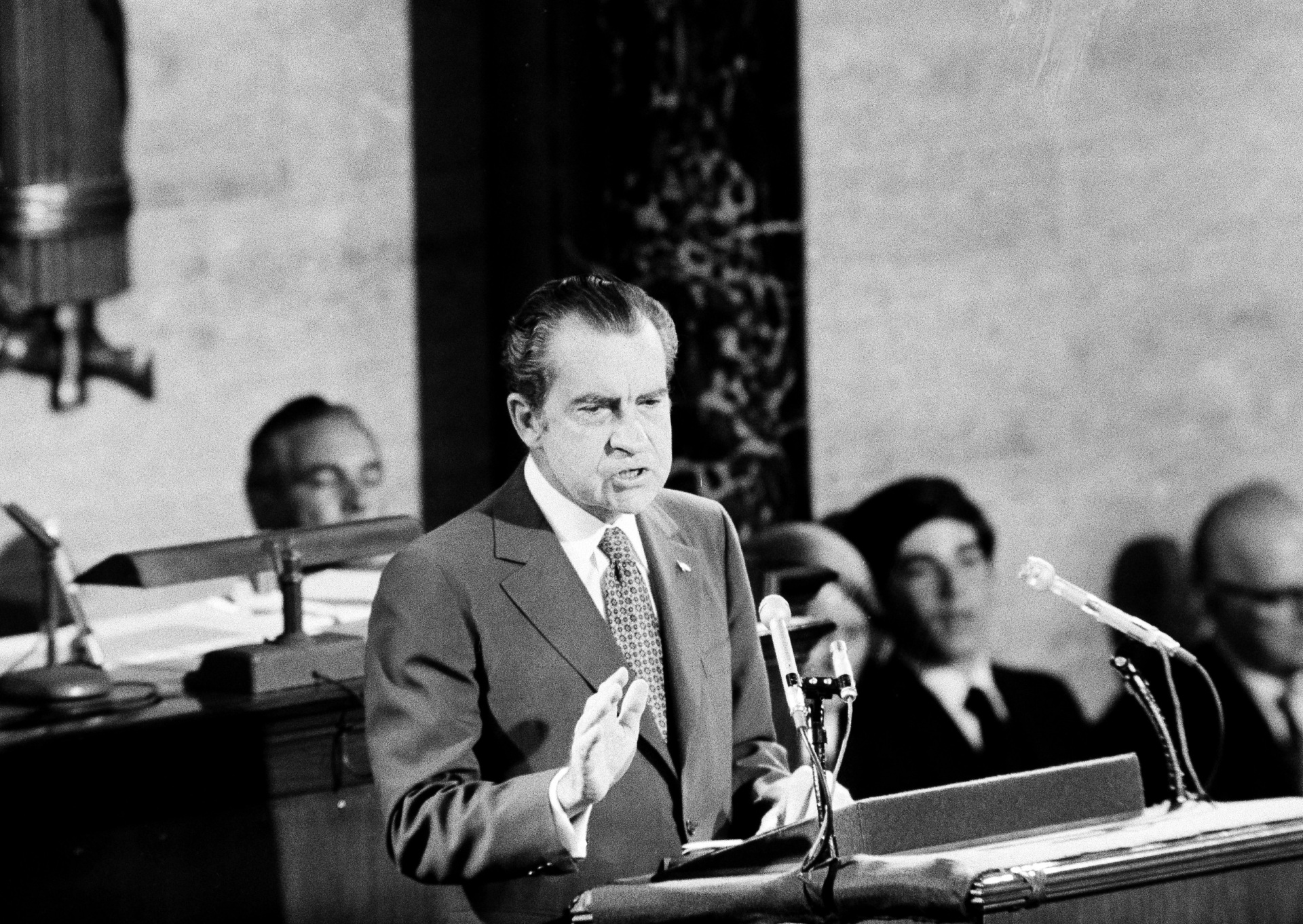

President Richard Nixon addresses a Joint Session of Congress 0n June 1, 1972. (AP Photo)

Congress had temporarily raised the debt ceiling from its “permanent” level of $400 billion to $465 billion. But this increase was set to expire on November 30, 1973, after which it would revert to the $400 billion limit. Nixon had utilized the “extraordinary measures” of his day to keep borrowing below the limit by impounding funds, which meant not spending money appropriated by Congress. (Congress later passed the Congressional Budget and Impoundment Control Act of 1974 to ban this practice.)

The end of November came and went with Congress still in a deadlock over the campaign funding measure, leaving the U.S. in breach of the debt limit. On the morning of December 3, 1973, Undersecretary of the Treasury Paul Volcker phoned Fed Chairman Arthur Burns to ask whether the Federal Reserve would refrain from tendering for redemption its holdings of Treasury bills as they matured. This would leave the U.S. Treasury with cash to pay other obligations and Treasuries, giving the government breathing room while the debate continued in Congress.

Arthur F. Burns, chairman of the Federal Reserve Board, is pictured in Washington, DC, May 21, 1970. (AP Photo/John Duricka)

Burns convened a committee that consisted of the Federal Reserve Board’s general counsel, its senior economist, its secretary, and other Fed officials, including attorneys from the Federal Reserve Bank of New York. The memo says that the General Counsel advised Burns that:

(1) there were no statutory impediments to the proposed action by the Federal Reserve;

(2) such action was not inconsistent with any outstanding regulation, rules, or authorizations of the Federal Open Market Committee;

(3) under his inherent powers the Chairman of the Committee had the authority to make the proposed commitment, even in the absence of any consultation with the Committee; and

(4) and that it would be desirable to give Committee members timely advice of the commitment, if made.

Burns Tells Volcker: Game On

Around 11 a.m. on December 3, 1973, Burns told Volcker that, as the memo explains, “if warranted by developments relating to debt ceiling legislation pending in Congress, the System would refrain from tendering to the Treasury for redemption on Thursday, December 6, 1973, its holdings of approximately $1.6 billion of Treasury bills maturing on that date.” In other words, Burns said he would go along with Volcker’s plan.

Paul Volcker, undersecretary of the Treasury for monetary affairs, on Feb. 10, 1972, in Washington, DC. (AP Photo/Harvey Georges)

The memo was written by Fed Board Secretary Arthur L. Broida and marked confidential. It was made public on August 21, 2020, but has gone unnoticed until now.

As it turned out, the Senate raised the debt limit to $475 billion that same day, making it unnecessary for the scheme to be executed.

The existence of this plan could have a major implication for today’s debt ceiling because the Federal Reserve holds over $5 trillion of U.S. Treasuries, including over $1.1 trillion maturing over the next 12 months. If the Treasury did not need to pay off those bonds, it would greatly enhance the ability of the Biden administration to pay other obligations as they come due.

There’s been no indication from the Biden Treasury Department or the Federal Reserve that a similar accord has been worked out.