A 2008-Style Run on the Fed

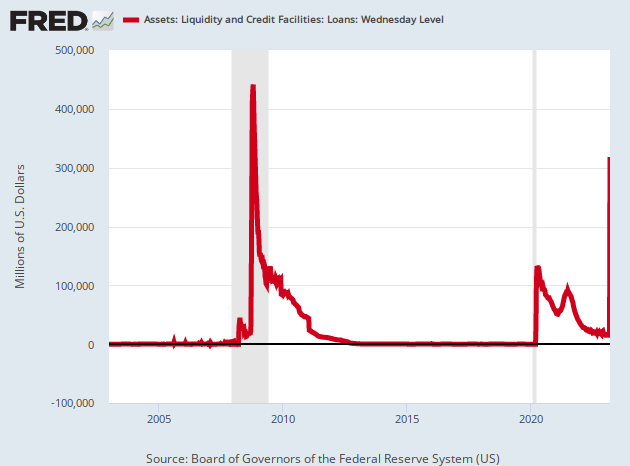

Borrowing from the Federal Reserve has skyrocketed.

The Federal Reserve on Thursday released its latest weekly snapshot of the central bank’s balance sheet. As of March 15, the level of borrowings from the Fed’s liquidity and credit facilities had risen nearly 2,000 percent from the prior week, rising from $15.2 billion to $318.1 billion.

To put that in historical context, the 2020 pandemic level of borrowings reached only $129.6 billion. The last time borrowings were this high was November of 2008, following the collapse of Lehman Brothers.

Lehman Brothers world headquarters is shown in New York City on September 15, 2008, the day the 158-year-old investment bank filed for bankruptcy. (AP Photo/Mark Lennihan)

Lending under the Fed’s “primary credit” facility—known as the discount window—jumped from $4.6 billion to $152.9 billion. The Fed describes this as “a lending program available to depository institutions that are in generally sound financial condition. Primary credit is available in terms from overnight to 28 days. In extending primary credit, Reserve Banks must judge that the borrower is likely to remain eligible for primary credit for the term of the loan.”

The other half of the loans came from “other credit extensions,” most likely the Fed’s new Bank Term Funding Program. This is the facility that lets banks borrow against Treasuries and government-backed mortgage bonds at par. The goal is to provide banks with liquidity without causing them to realize losses by selling loans at a discount because their coupons are below the prevailing interest rate.

In the chart below, you can see the rise in borrowings from the Fed all the way on the right side. It’s easy to miss because it is a straight up line near the edge.

Faster Than the 2008 Financial Crisis

As you can see, borrowings reached a higher level in 2008. What’s less visible in the above chart, however, is the fact that it took several weeks for Fed credit to get that high in 2008. Borrowing went from $23.6 billion on September 10, to $121.2 billion on September 17, to $262.3 billion on September 24, to $409.5 billion on October 1.

This time around, Fed credit grew by more than $300 billion in a single week. That’s an unprecedented pace of growth of the Federal Reserve’s balance sheet.

The implication of this is that financial distress in the banking sector is likely much wider than was apparent. Banks are scrambling for liquidity. This is more or less a run on our central bank. Fortunately, the Fed has unlimited liquidity.

This will put additional pressure on the Fed to pause rate hikes and suspend quantitative tightening next week. What’s the point of draining reserves with one tool while increasing them through the discount window and the new term facility? Effectively, the Fed is already engaged in a new round of quantitative easing.