Back when Jesse James prowled the land, the savings of the citizenry was constantly under threat by bandits looking to heist their money. These days, the money itself is stealing the savings of people in the form of high inflation and crashing financial markets.

Yesterday, we pointed out that the first half of the year was the worst for stocks since 1970. The S&P 500 dropped by around 20 percent, just shy of the 1970 bear market record of 21 percent. The Nasdaq Composite was down by 29.5 percent, the worst decline ever. The Dow Jones Industrial Average fell 15.3 percent, the worst since 1962.

We must confess, however, that things were even worse than we thought. Those declines are in nominal terms, meaning they do not take into account the massive inflation we’ve experienced in the first half of this year. Stocks were falling in dollars terms, but those dollars themselves were declining in value. As we’ve pointed out again and again, inflation introduces chaos into financial calculations that can often conceal deep points of economic stress.

Michael Hartnett, the chief investment strategist at Bank of America Securities, ran the inflation-adjusted numbers in a note for clients this morning. He found that this has been the worst start of the year for the S&P since 1872, the year Jesse James and Cole Younger led their gang to rob a bank in Columbia, Kentucky, and ended up shooting a teller who refused to open the vault.

The James Boys, Jesse and Frank, sit in front of the Younger Brothers, Cole and Bob. The four men formed a gang that robbed trains and banks across the American midwest. (Corbis via Getty Images)

At the time, the country was led by President Ulysses S. Grant, a military hero who was not exactly an ace at economic policy. The following year, the country fell into what was then known as the “Great Depression.” This severe downturn lasted from 1873 to 1879. At 65 months, it is still to this day the longest-lasting contraction identified by the National Bureau of Economic Research, outlasting the 43-month contraction of the Great Depression of the 1930s. Ten states, scores of railroads, hundreds of banks, and thousands of businesses went bankrupt during the 1870s Great Depression.

As bad as that sounds, Hartnett points out that 2022 is looking like the worst year for government bonds since 1865. Government bonds fell 15.4 percent in the first half of the year, even before adjusting for inflation. Year over year, they were down by around twice that. And that is before adjusting for inflation (which is hard to do when measuring bonds issued in a variety of currencies from all around the globe.)

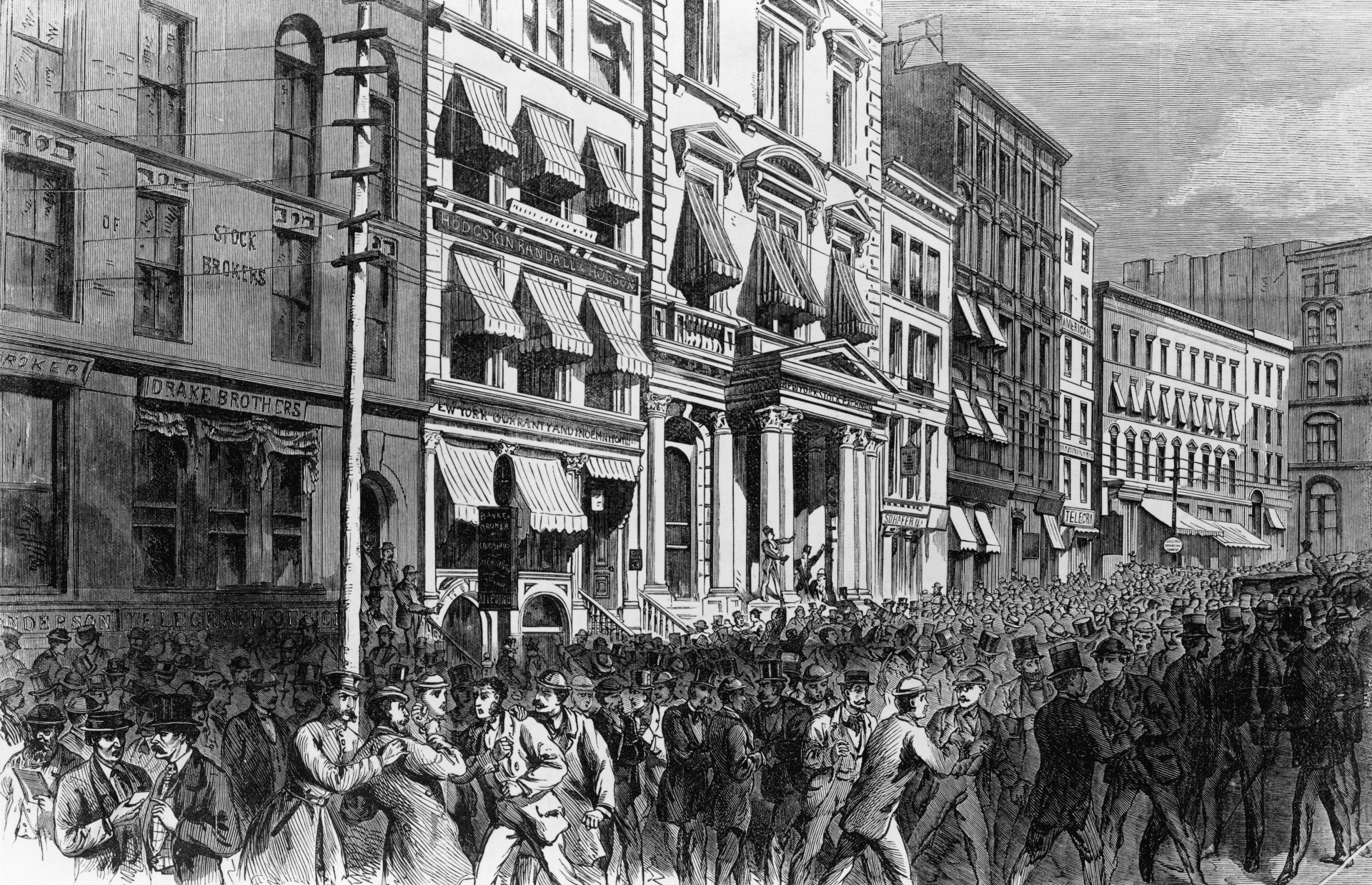

A panicked crowd on Broad Street, New York City, after the closing of the stock exchange doors during the Panic of 1873 on September 20, 1873, an event that triggered a period economists refer to as the Long Depression. (Kean Collection/Archive Photos/Getty Images)

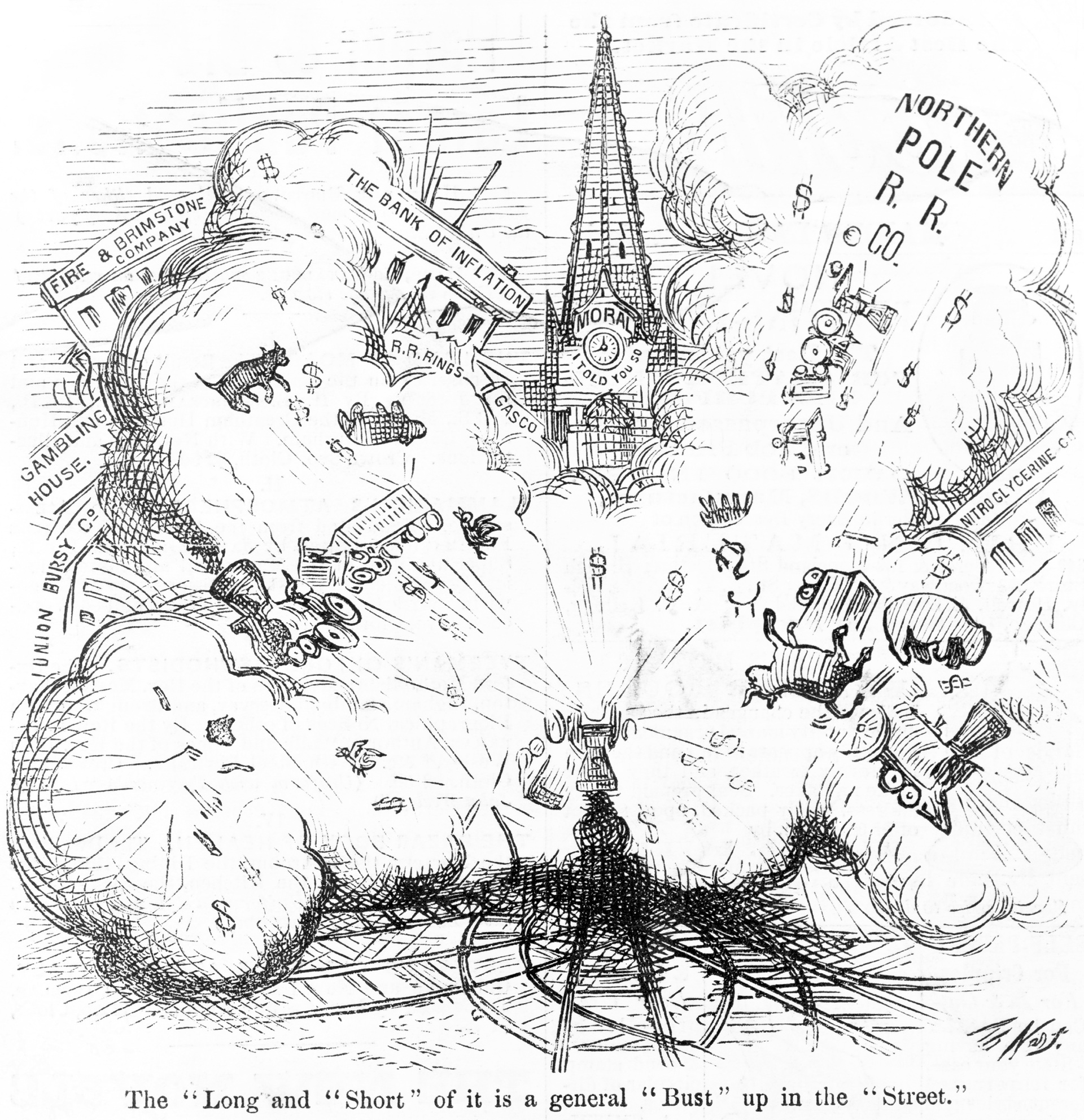

A political cartoon by Thomas Nast showing the financial Panic of 1873 being caused by abnormal growth in the railroad industry. The image depicts an explosion blowing up the Northern Pole Railroad Company, The Bank of Inflation, and the Fire and Brimstone Company. The inscription below reads: “The ‘Long’ and ‘Short’ of it is a general ‘Bust’ up in the ‘Street.’” (Interim Archives/Getty Images)

This does not mean that there was no money to be made in the first half of the year. As everyone knows, oil and gas prices have exploded higher. Commodities overall had their best inflation-adjusted first half of the year since 1946, according to Hartnett. Oil rose 46 percent, natural gas 74 percent, and iron ore 28.2 percent.

Certainly, recent economic data will do little to reassure investors about the economy. Construction spending unexpectedly declined in May, the first drop in eight months. Strikingly, single home construction spending was flat for the month—before adjusting for inflation. In inflation adjusted terms, then, construction has rolled over and is declining rapidly. The Institute for Supply Management’s assessment of manufacturing showed growth continued, albeit at the slowest pace since May 2020, in June. But both employment and new orders fell into contraction territory.

The Federal Reserve Bank of Atlanta’s GDPNOW economy tracker had fallen into negative territory on Thursday. On Friday, it plunged even deeper to minus 2.1. Bank of America slashed its forecast for second quarter GDP to zero—before it got a look at construction and the ISM report.

Next week’s focus will be on the nonfarm employment report. All signs point to ongoing strength in the labor market, with the consensus for job growth at 250,000 and the unemployment rate at 3.6 percent. A big question mark is how long it will take for negative GDP growth, sharply rising interest rates, and high inflation to throw sand into the gears of the labor market.