Memorial Day is about remembering America’s fallen who died in the service of their country. One forever-young unsung hero’s sacrifice ,although largely forgotten, was crucial in realizing the idea of liberty in a country yet to be born.

Countless times, the fate of the nascent American nation depended on the right person being in the right place at the right time–like the gallant 26-year-old Marblehead captain James Mugford Jr. who captured the largest single prize of the Revolutionary War, the Hope.

On May 10, 1776, five weeks into her journey across the Atlantic, the Hope, a British 282-ton transport ship carrying a staggering 1,500 barrels of priceless gunpowder, mysteriously separated from her eleven-ship escort in a thick fog. Her disappearance was even more suspicious because, before their departure from Cork, the flotilla commander had received an anonymous letter questioning the loyalties of the ship’s master, Alexander Lumsdale.

Seven days later, American privateer Captain Mugford spotted the lone vessel creeping toward Boston through his spyglass. His privateer, the Franklin, had set out from Beverly, Massachusetts, two days earlier with only a skeleton crew of twenty-one men because of the difficulty of recruiting mariners as newly established prize courts had been holding up their wages. Mugford had only managed to secure his current crew because he had personally secured wages for a dozen core men.

With the Hope in sight, the Marbleheaders put the sails of the Franklin to the wind and caught up with the heavy British ship. Ignoring the Hope’s 4- and 6- pound swivel guns, they courageously boarded the larger vessel and were shocked to find themselves evenly matched to the Hope’s crew of eighteen. They were even more surprised when Captain Mugford demanded her manifest from Captain Lumsdale. The prize carried one thousand carbines, stacks of bayonets, five gun carriages, piles of cartridge boxes, and an astonishing 1,500 barrels of gunpowder–enough powder to supply either army’s needs for a month.

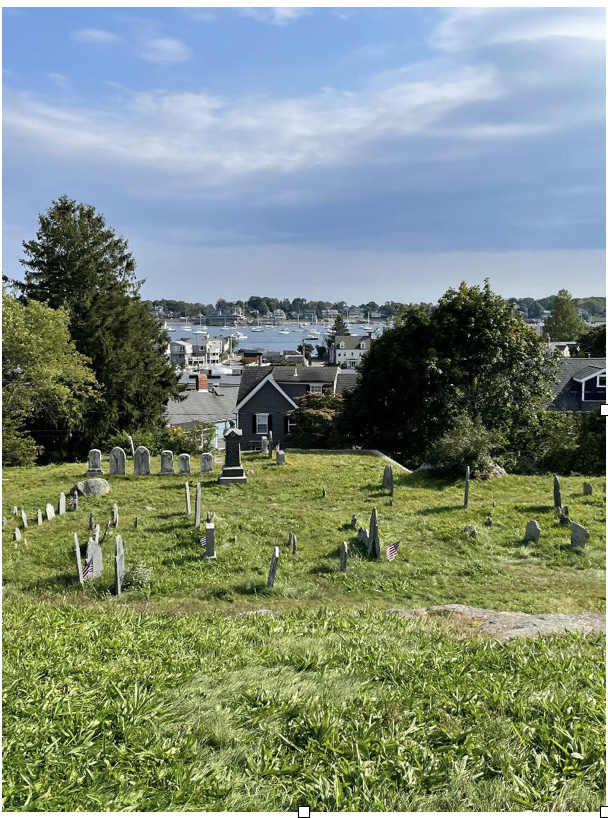

Adding to the appearance of divine providence, the Hope, escorted by the Franklin, ran aground just outside Boston harbor. Two months earlier, Congress had declared a day of prayer and fasting. Colonial church goers emerged from their respective houses of worship on the designated afternoon of May 17 to see the captured ship in the harbor as if in direct answer to their prayers. Elated, they immediately began divesting her of her precious cargo and dispersing it.

Mugford’s remarkable story and dozens of others are told in the bestselling book The Indispensables: Marblehead’s Diverse Soldier-Mariners Who Shaped the Country, Formed the Navy, and Rowed Washington Across the Delaware. The book recently released in paperback is a Band of Brothers-style treatment of the regiment from Marblehead, Massachusetts, a unique largely unknown group of Americans who changed the course of history.

Mugford intended to return to sea to hunt more British transports joined by Lady Washington. But as the two American ships sailed out of Boston Harbor, Franklin grounded near the same spot as had the Hope.

Despite the Crown evacuating Boston a month earlier, two British warships still lurking outside Boston Harbor saw Mugford’s stranded vessel. The British captain ordered a boarding party to attack the disabled ship. That night between nine and ten o’clock, the British sailors, led by Lieutenant Johnathan Harris carrying a silver-hilted sword, rowed silently toward the Franklin and the Lady Washington in at least five boats.

Mugford hailed the boats as they slithered across the black water toward his vessel. In answer, they called back that they were from Boston. Mugford warned the boarding party, “Keep off, or I will fire upon [you]” as he simultaneously commanded his men to ready the guns and ordered his anchor cut so that the Franklin’s broadside, and her guns, faced the oncoming rowboats. Ignoring their pleas, for God’s sake, not to fire, Mugford fired his musket, and the crews of Lady Washington and Franklin followed suit. The musket and cannon balls sailed across the water, tearing into the small boats as well as the flesh and bone of the men aboard them. They managed to sink two small boats, but before the Franklin’s cannon could discharge another deadly blast, some of Lieutenant Harris’s men were already aboard Mugford’s ship. Mugford and his men peppered the boarders with small arms and harpoon spears, even cutting off the hands of soldiers as they laid them on the gunwale.

Mugford was described “with outstretched arms . . . righteously dealing death and destruction” before he received a mortal wound to his chest. He cried out, “I am a dead man, don’t give up the vessel, you will be able to beat them off.” And beat them off they did, sending the remaining combatants limping back to the British warships, although they lost their beloved captain in the fight. His crew sailed his body back to Marblehead, where thousands thronged to pay their respects, and he was buried with highest honors as the first captain in Washington’s navy to die in combat. James Mugford, forever young, turning 27 years old on the day of his death, would never see America declare independence a month and a half later, but the priceless cargo he seized would help secure our freedom which is never free. Today we remember his and so many other Americans who gave their last full measure of devotion for the cause of liberty.

Patrick K. O’Donnell is a bestselling, critically acclaimed military historian and an expert on elite units. He is the author of twelve books, including The Indispensables, which is featured nationally at Barnes & Noble, Washington’s Immortals, and The Unknowns. O’Donnell served as a combat historian in a Marine rifle platoon during the Battle of Fallujah and often speaks on espionage, special operations, and counterinsurgency. He has provided historical consulting for DreamWorks’ award-winning miniseries Band of Brothers and documentaries produced by the BBC, the History Channel, and Discovery. PatrickODonnell.com @combathistorian