WASHINGTON, DC – Three former U.S. attorneys general — including Bill Barr, who does not support Donald Trump’s campaign for the Republican nomination — insist that Trump is constitutionally qualified to be on the presidential ballot, in a U.S. Supreme Court brief their lawyers filed on Thursday.

Along with Barr, former Republican Attorneys General Edwin Meese III and Michael B. Mukasey, as well as several law professors, comprised the amicus in the Trump v. Anderson brief. After the Colorado Supreme Court ruled in a 4-3 decision that Section Three of the Fourteenth Amendment, colloquially known as the “Insurrection Clause,” bars Trump from the ballot, his legal team and the Republican Party of Colorado challenged the effort.

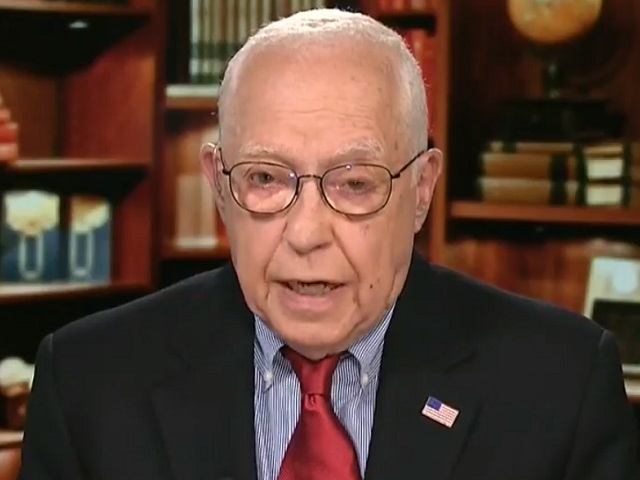

US Attorney General William Barr (Photo by Brendan Smialowski / AFP) (Photo by BRENDAN SMIALOWSKI/AFP via Getty Images)

The brief, filed by counsel Gene Schaerr of Schaerr Jaffe LLP, argues that the Colorado court’s decision is a “misrepresentation” of the clause and, if upheld, the “ruling would create a precedent with ruinous consequences for our democratic republic.”

The argument at the center of the brief –of which law professors Steven Calabresi and Gary Lawson and the group Citizens United are also Amici Curiae– is that the clause does not pertain to candidates for the presidency:

This is evident in Section 3’s text, which omits the President, instead specifying certain offices such as Senator and Representative. Earlier versions of the proposed text included President and Vice President, but later versions excluded those offices, and instead disqualified presidential electors who would choose the occupants of the presidential and vice presidential offices.

The amicus cites the historical record of the Fourteenth Amendment, which was passed soon after the United States Civil War in 1868.

Former Attorney General Edwin Meese applauds as President Donald Trump speaks during a ceremony to present the Presidential Medal of Freedom to Meese, in the Oval Office of the White House, Tuesday, Oct. 8, 2019, in Washington. (AP Photo/Alex Brandon

“Historical records, moreover, reveal that the Framers and ratifiers of the Fourteenth Amendment were not concerned that a Confederate leader could attain the presidency,” the brief noted. Instead, the framers and ratifiers harbored worries “that former Confederates might be elected to the House or Senate, which explains why those offices are enumerated in Section 3.”

“Winning offices in States of the former Confederacy was the only realistic risk, and Section 3 was tailored to address that concern,” the brief adds.

What is more, the language of the text lists a hierarchy ranking of public officials, beginning with U.S. Senators and U.S. Representatives, as the brief highlights, and makes no explicit mention of the office of the presidency. The brief argues that other language included in the section was not understood historically to include the presidency:

The text speaks to a hierarchy of public offices in descending rank order, and its reference to an “officer of the United States” low in that hierarchical list cannot include a President because an office “under the United States” and “officer of the United States” did not include the presidency as those terms were historically understood.

The amicus goes on to assert that “even if the conclusion that he engaged in an insurrection were correct, President Trump cannot be excluded from any presidential election ballot on that basis.”

Under the second key argument, they note that Section Three is not self-executing and, therefore, led to Congress eventually establishing a federal insurrection statute, 18 U.S.C. § 2383, which bars someone convicted of rebellion or insurrection from serving in any political office.

“But President Trump has never even been charged with violating Section 2383, much less convicted under it,” the brief reads.

Thirdly, the amicus argues the “Court should resist any interpretation of Section 3 that empowers partisan public officials to unilaterally disqualify politicians from the opposing party.” Notably, Maine Secretary of State Shenna Bellows has followed the Colorado Supreme Court’s move and unilaterally ruled that Trump is ineligible for the Maine ballot, citing the “Insurrection Clause.”

The brief proposes “a hypothetical in which the partisan shoe is on the other foot,” reading:

If the Colorado decision were correct, the Georgia Secretary of State, a Republican, could unilaterally disqualify President Biden, a Democrat, from that swing State’s ballot one day before the ballot certification deadline—perhaps finding that some of President Biden’s policies were lawless in such a manner as to constitute, in the Secretary’s view, an “insurrection.” Other Republican officials are threatening to do just that.

Ultimately, the brief concludes that without a new statute to Section Three of the Fourteenth Amendment passed by the U.S. Congress, it bars no American from running for the presidency.

The full text of Section Three of the Fourteenth Amendment is below:

No person shall be a Senator or Representative in Congress, or elector of President and Vice-President, or hold any office, civil or military, under the United States, or under any State, who, having previously taken an oath, as a member of Congress, or as an officer of the United States, or as a member of any State legislature, or as an executive or judicial officer of any State, to support the Constitution of the United States, shall have engaged in insurrection or rebellion against the same, or given aid or comfort to the enemies thereof. But Congress may by a vote of two-thirds of each House, remove such disability.

The case is Trump v. Anderson, No. 23-719, in the Supreme Court of the United States of America.

Disclosure: Ken Klukowski, senior legal contributor at Breitbart News, is senior counsel at Schaerr Jaffe and co-authored the brief with Gene Schaerr.