When a radical right party wins a state election in Germany, the headlines write themselves. This month’s victory for the Alternative for Germany was greeted in much the same way across the world. CNN labeled AfD “the first far-right party to win since 1945.” London’s Daily Telegraph went with “first since the Nazi era.” Germany’s own DW preferred “first since World War Two.”

It got me thinking. There are indeed parallels with Nazism, but not the ones that most people make. The AfD is not about to invade Poland or reestablish the Hitler Youth. Rather, it is part of the populist wave that has surged across Europe in response to rising levels of immigration and crime.

Don’t get me wrong, the AfD is an outlier in its vehemence. Sometimes, the label “far right” is applied by hypochondriac commentators to any form of social conservatism of which they disapprove. Sometimes, parties that used to have nasty leanings clean up their act and become mainstream.

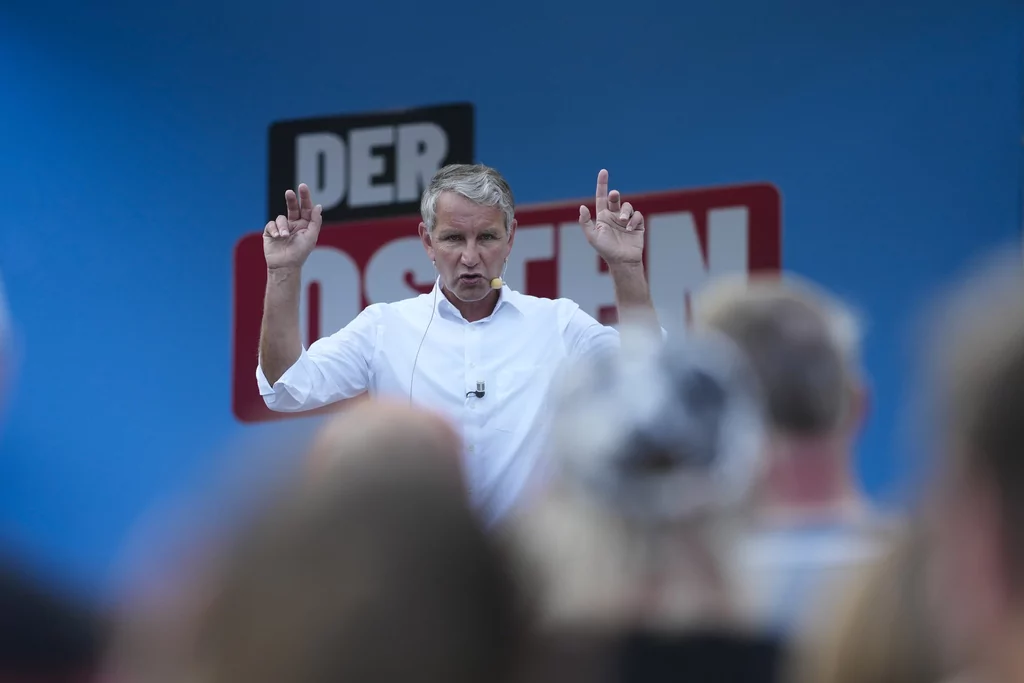

But the AfD has moved in the opposite direction. I used to sit in the European Parliament with its founders, a pleasant group of professors and business leaders who made thoughtful arguments against the euro. They were pushed aside by a new leader who wanted the party to be narrowly anti-immigrant. Then she was pushed aside by someone even more hard-line.

Why is the AfD winning in a country that is more nervous than any other about national chauvinism? What is driving people to a gang of ethno-nationalists with a soft spot for Russian President Vladimir Putin?

One word: crime. There has been an upsurge in Islamist violence over the past decade in Germany. Shots were recently fired at the Israeli Consulate in Munich. A police officer was murdered by a jihadi in Mannheim. Days before the AfD victory, three people were stabbed to death in Solingen by a Syrian devotee of the Islamic State group who had gone missing after being refused refugee status. They died, with grisly symbolism, at a “festival of diversity.”

Behind headline outrages is a sharp rise in day-to-day crime. Last year, there were 27,470 criminal offenses in German schools, a rise of 27% from 2022, prompting calls for trained security officers. How many of these crimes were committed by students from immigrant backgrounds? The authorities won’t say. But I wonder how much support for the AfD from young people has to do with their schoolyard experiences.

The leader of Germany’s Christian Democrats, Friedrich Merz, uses language that would recently have been unthinkable from a mainstream politician. “On average, there are two gang rapes per day, the vast majority of them carried out by migrants,” he says. The numbers back him up. Of 209 gang rapes reported to police in Germany’s most populous state, North Rhine-Westphalia, nearly 80% of suspects were from immigrant backgrounds.

Historians usually underestimate the impact of rising crime when explaining the Nazi ascendancy. Few Germans, beyond a handful of ideologues, had much interest in biological antisemitism. Yes, there was resentment about the 1918 settlement, but foreign policy rarely determines election results. The 1929 crash played a part in discrediting the established parties, but poverty is not the all-purpose explanation that commentators think, and Germans cheerfully went on to accept the Nazis’ “guns before butter” policies.

No, the issue that drove many respectable Germans into the embrace of Hitler and his deranged mob was the unrest that overtook what had until then been the most disciplined and orderly country in the world.

The Australian political scientist Karen Stenner has argued convincingly that what tips ordinary people into backing extreme and authoritarian policies is the perception of what she calls a “normative threat,” an apparent danger to their way of life.

CLICK HERE TO READ MORE FROM THE WASHINGTON EXAMINER

In the Weimar Republic, the normative threat took the form of political violence, street brawls, and, not least, a surge in ordinary crime. The press became obsessed, for example, with a big bank robbery that had evidently been committed by a pair of brothers with criminal pasts, but against whom the police could not find evidence. By 1930, voters were ready to back anyone who would put a stop to the lawlessness — even the Nazis, whose brownshirts had been responsible for much of it in the first place.

Today, the normative threat comes not only from the upsurge in crime but from the related sense that mass immigration is forcing unwelcome societal changes — for example, in attitudes to free speech, public modesty, and the role of women. The media might not like to discuss these things, but voters have eyes. This could be just the beginning.