Those not deeply immersed in politics may not be familiar with Jeremy Carl, the distinguished author and senior fellow at the Claremont Institute who also served as former President Donald Trump’s deputy secretary of the interior.

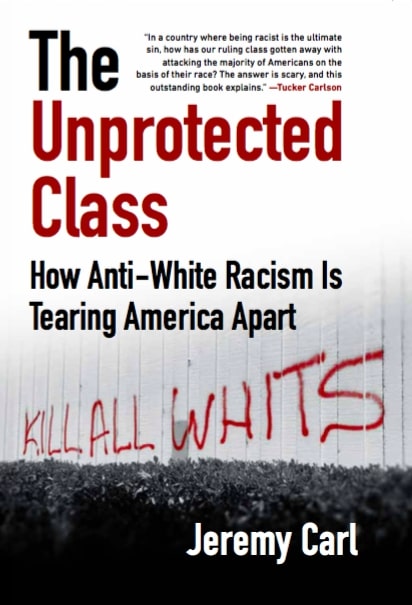

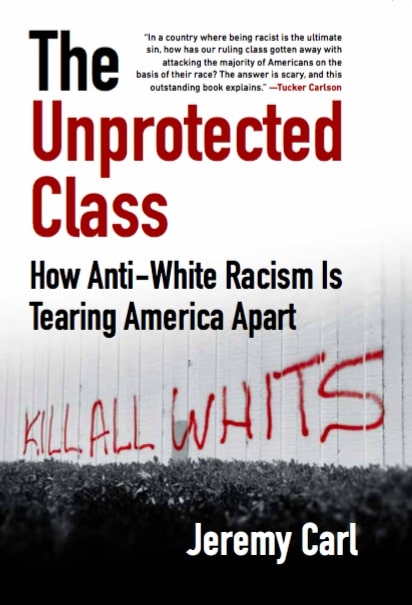

But chances are very good you’ll be hearing a lot about him and his new book, “The Unprotected Class: How Anti-White Racism Is Tearing America Apart” (Regnery), after it goes on sale today.

If the title alone isn’t enough to send the liberal mob into a rage, the book’s central thesis will have them firing up the cancel culture machine.

In this landmark work, Carl asserts that if there is anything resembling systematic racism in America these days, it is directed at the white majority that is increasingly becoming an unprotected class, openly discriminated against in the name of “social justice.”

Moreover, he asserts that this anti-white movement has been orchestrated primarily — though certainly not exclusively — by white liberal elites in an effort to “justify the expropriation of land, property and other wealth from whites while instituting a permanent regime of anti-white employment and legal discrimination.”

“Sometimes you forget how pervasively this brain worm has just burrowed in and altered any sort of rational thinking of these leftists in particular,” Carl told The Western Journal in a video interview.

“But I think the problem is that there are a lot of very well-meaning people, people of all races, who get trapped by this type of thinking because that’s what they’re hearing from their TV. And I wrote this book as kind of an antidote to that.”

Carl traces this racialist ideology to its roots approximately 60 years ago and reveals how it flourished during the Obama administration and then exploded in the aftermath of George Floyd’s death. (He even draws a stark contrast between the glorification of Floyd and the demonization of Kyle Rittenhouse.)

He also exposes the movement’s destructive messaging — which has become increasingly overt — in government, law, the military, education, business, entertainment and even religion.

Applying rock-solid scholarship to topics and watershed events spanning most of American history, Carl manages to refute many of the familiar tropes the left clings to and seeks to perpetuate whenever the well-worn race card is thrown down.

Here, in his own words, is Carl on how we arrived at this dangerous juncture and why we must make a major course correction on behalf of all races in America.

TWJ: You contend that we are now living in what amounts to a post-white America, that if the U.S. is currently systematically racist at all, it’s anti-white, and that privilege does not currently reside in whiteness. Can you explain those thoughts?

Carl: Well, the post-white America, I think, is a concept that people are still kind of getting their heads around. Even beyond that, it kind of speaks to a certain cultural level and setting a cultural tone.

We’ve certainly moved into a post-white America in terms of any talk of privilege. I think it’s really clear. If it were really advantageous to be white in the current environment, people would not be rushing, as they are in many different ways that I document in the book, to identify as something other than white.

You have it particularly in more liberal spaces, but very important establishment spaces like academia. You have just an epidemic of fake minorities out there, but you similarly see it in college applications, in job applications — people who would seem, if you met them, to be white checking some other box if they feel that they could legally get away with it, or sometimes even if they can’t, because they understand that there are huge advantages to doing that.

You write that white people have internalized this anti-white racism to the point that it’s created what is generally referred to as “white guilt.” Can you elaborate?

One of the things I try to be clear about is I’m not letting minority political leadership off the hook, because I think they have a significant role to play in this dynamic.

In many ways, the kind of worst actors — both morally and in terms of their effects — are, in fact, liberal whites. One of the things that we’ve kind of internalized is this self-hatred, even to the extent that they attempt to push it on other people to try to get them to internalize it. It’s kind of fascinating.

There’s some really interesting survey data that has been collected. These are very large, kind of generalized, well-validated social science surveys. One of the things it shows is that if you look at the way ethnicities view themselves in America, people generally have an in-group preference. This is to say that you have some preference for a group of people that’s like you. So white people tend to like white people more, black people tend to like black people more, etc.

And as long as that’s kind of kept at a moderate level that it doesn’t get to be some extreme, there’s nothing particularly surprising or problematic about it. But it’s not huge for any group, any race. It’s kind of what you would predict — except for white liberals.

White liberals stand out as this huge anomaly in the entire social science research in that they have a dramatic hatred of white people. They prefer other groups, by far, and they dislike their own group. And again, this is a very well-validated finding. I think that explains a lot, given the power of white liberals in our society, for why we are where we are.

What is the motivation of white liberal elites in generating this wave of anti-white discrimination?

I think there are a couple of things here. One is that there is a deep moral need. People are sort of looking for meaning. They’re looking for a moral need to kind of say, “Well, we’re better than this other group of whites. You know, we’re not the bad guys.” So there’s a certain moral self-validation they feel by beating up on themselves in this way.

And then I think also they don’t even in some ways see themselves as part of the same group. So when they talk about whites, they’re almost not even seeing themselves. They’re seeing some other group, and they’re trying to say, “You know, we’re better.”

I’m thinking of Rob Henderson, who’s come up with this concept called “luxury beliefs,” which are essentially really bad beliefs about society that are not true. The only way that you can hold them and kind of exist well in society is if you have a lot of other advantages. And so I think anti-whiteness for affluent whites is a luxury belief.

If you are in a situation in society where you can afford to take that hit and to be less likely to get the job or to be less likely to get the place in school [due to anti-white discrimination], you’re in that position because you actually already have a lot of benefit, usually financial and economic. A middle-class white person can afford to be discriminated against in that way.

But at another level, it’s kind of a class signal of saying, “Hey, I can still do really well, even if you stack all these things against me. That makes me better.” That’s also one of the reasons I think some whites are very uncomfortable with even talking about that, because they feel like, “Oh, well, we don’t want to be victims, and I don’t want to be a victim either.” But this is about kind of demanding justice under the law. You can’t be afraid to speak out on your own behalf.

You write that this anti-white racism wave took off under Obama and then exploded with George Floyd’s death, but it was already in motion long before that and can be traced to the 1964 Civil Rights Act. Is that correct?

I think, obviously, the Civil Rights Act of 1964 was a watershed in changing things around pretty dramatically. And by that I don’t mean in any way to suggest, obviously, that things were perfect before then. The reason we got that act is because it was responding to very real discrimination that African-Americans and other minorities were experiencing in society at that time. And so my goal here is not to kind of relitigate the 1964 Civil Rights Act. It was a blunt instrument, but there was a need to do something.

My point would be to say, “Hey, we’re as far away now in society and culturally, maybe even further, from the country that passed that act 60 years ago as they were to the Wright brothers flying the first airplane.” There have been a lot of changes. There have been a lot of things that have happened in society.

I think the 1991 addition to the Civil Rights Act did a lot of things that kind of made some of the bad aspects of it get turbocharged. But there is a whole series of administrative decisions kind of made by the deep state and unaccountable bureaucrats, in many cases, directly opposed to what the intention of the act was. I’m thinking particularly here of “disparate impact,” which is a kind of turbocharged machine for discriminating against white people.

One of the most troubling parts of the book is when you write that “for those who have eyes to see it, a great deal of interracial violence, of which whites are disproportionately and increasingly victimized, has an overt or scarcely hidden undertone of racial revenge.” Can you explain?

To put it very simply, whites are overwhelmingly the victims of interracial violent crime, not the perpetrators of interracial violent crime. Some of that is categorized as hate crimes, some of it isn’t. I suggest that there is a political undertone to what gets categorized as a hate crime. But I think particularly, although not exclusively, with respect to black-on-white crimes, there are elements of racial revenge or racial targeting.

This is a very complex dynamic. It’s not something that just kind of lends itself to a quick sound bite because you also have, for example, a huge amount of black-on-Asian crime. Those things tend not to be categorized legally as hate crimes. But I would argue, to the extent that we really even want to have that taxonomy, these are, in fact, unreported hate crimes.

You explain that the fundamental trend of anti-white racism was implemented in society to “justify the expropriation of wealth from whites.” But you also write that there’s no real central intelligence to this. Can you explain that seeming contradiction?

This is an important part of the thesis. There are a couple of things going on. When you see ideas in politics, there is always some reason why they have a balance. As I point out in my book, it didn’t spring, like Athena from Zeus’ head, fully armed and ready for battle. There’s a gestation period. There’s a reason why. And I think I kind of offer a pretty persuasive argument for why expropriation is ultimately the name of the game.

But again, as I say in the book, there are no protocols of the authors of anti-whiteness out there. There is a small number of members of what I would call the inner party. This is kind of a political science term. Of course, they don’t tend to see themselves as villains, but they at least understand what they’re doing. They understand that ultimately it’s about, “Well, white people have these various resources and we want them, and we’re going to use these sorts of arguments to justify taking them.”

That group wouldn’t be able to have the power without this much bigger group [of] largely unwitting accomplices. And they are people who just look at, “Well, there’s an unequal social situation,” or even a perception of an unequal social situation, because as I show with respect to crime or things like that, I mean, often the narrative runs completely counter to reality.

And the outer party group is manipulated by that inner party group to kind of advocate for these things in the name of fairness, equity or social justice. They don’t even necessarily perceive that they’re doing anything that involves a resource transfer at all. They’re just demanding fairness. That’s in their mind, but that’s ultimately what ends up happening.

You characterize “diversity,” “equity” and “social justice” as virtue-signaling terms that are broad in scope and can be applied in millions of ways but that are also a means of controlling power. Is that correct?

Absolutely, and “diverse,” at this point, with some rare exceptions, literally just means less white. There are times when you can look at the way the word “diverse” is being used and realize that if you substituted in the term “less white,” it would be infinitely more accurate as a description of what’s going on.

People will say, “We need to make it more diverse.” And you look at the group and it’s already, let’s say, more diverse on a population basis than the United States, or at least maybe among the comparable set of people that they are looking at. They talk about making engineering or computer science more diverse when you’ve already got, you know, 50 percent Asian-American software engineers or something like that, and whites are already underrepresented.

The most plausible way to understand these types of words is that diverse, in this case, just means less white, and it’s a more polite way of saying it.

With regard to Big Tech, you also wrote about other terms — “misinformation” and “disinformation” — as code for silencing conservative white voices. Can you explain?

We don’t need to relitigate the 2020 election, but this was part of the way in which the 2020 election was manipulated. Essentially, you define misinformation in a way that you simply end up censoring particularly conservative white voices.

And, of course, I’m not in any way trying to claim that there aren’t conservative whites or whites of other types who create misinformation. But it’s simply to say that if you look at the way it’s being used, it’s used only as a weapon, asymmetrically, so that if a conservative white says something that is misinformation, it will always be flagged. If another group says it, it won’t be flagged.

And even more powerfully, sometimes there are things whites may say that are simply unpopular with the people who run Google but are not, in fact, misinformation at all. You saw a lot of this in the pandemic, for example, being flagged as misinformation. That’s kind of the way this game works.

You write extensively about unchecked immigration as a force that has long pulled the country leftward and ultimately has led to anti-white attitudes. You say that some elements of the Great Replacement Theory are real. Can you speak to that?

I’m not going to say that every single element [of the theory] is something that I’m going to agree with. But in the broad sense, this is true.

And this is why they don’t want you to talk about it, which is [that] whites are intentionally being demographically replaced in the United States, and it is to increase the power of the left. It is to tear down, culturally, the kind of edifice that we have. And I would argue, in many cases, [it’s also] for business people to have power. You’re weakening workers’ power. You’re kind of making everybody an undifferentiated consumerist mass.

So there are a lot of things at play there. But this is a very intentional strategy. It’s a way of attempting to reduce solidarity within the country and get people quarreling with each other because then they can be more easily controlled. And so I think this is absolutely happening.

I talk a little bit about my colleague and friend Michael Anton, who has a great term: “celebration parallax.” This is to say that something is either true and wonderful or false and it’s terrible that you should even mention it, depending on who says it.

So I document in the book a whole bunch of times where major figures on the left are effectively celebrating what is effectively the Great Replacement, and nobody really says anything bad about it. But whenever conservative whites in particular say, “Hey, this is what’s going on,” it’s immediately, you know, “the Fourth Reich is upon us.” So that’s the political environment we’re dealing with.

The Democrats haven’t won the white vote or even come particularly close since the 1964 presidential election, [Lyndon] Johnson vs. [Barry] Goldwater — that was just kind of a general landslide. White Americans are almost living under an occupation government, effectively, in that they have a supermajority of the electorate every single election, they never vote for the Democrats at the national level, and yet we frequently have Democratic leadership.

And then, of course, we have this deep state that is basically entirely controlled by the Democrats. White Americans have been effectively disempowered by their government in this way.

It’s also generally argued that it’s much easier to control an electorate that is unskilled and less educated and therefore reliant on government and that is going to vote Democrat, at least the first generation. Do you agree?

I completely agree with that. And I think it’s also just easier to control a less unified electorate, period. So there are all sorts of advantages for groups pushing for this. Again, I want to be very clear — because I am clear about this in the book as well — I’m not blaming the immigrant groups.

You say that combating anti-white discrimination is “not something we should do for whites only, but for all Americans. Because if we continue to let the left engage in continuous and rampant race baiting without resistance, tensions will increase until they ultimately boil over, likely with terrible consequences.” What do you envision that boiling over could look like?

I don’t have a crystal ball, so one can only speculate. But I think you can look throughout history — and I’m not just talking about American history — where everything is kind of fine in society, but there are some problems that we kind of know about, and we feel like it’s manageable until all of a sudden it isn’t. And things can change very dramatically.

One of my many concerns — this is just one of a thousand things that could happen — is that, effectively, the discrimination and the racism becomes so much that white Americans get pushed to the wall and they’re like, “We’re just not going to put up with this anymore.” And it becomes militarized in some way. You could hypothesize a million different scenarios involving a more conservative governor just saying, “Hey, we’re not going to listen to what the national government is saying about this.”

I don’t want to pretend that I’ve got some key to figuring out what this is. But if that turns into a scenario where violence is exchanged, that’s a worst-case scenario for the U.S. that we wind up in a civil conflict. But to think that it couldn’t happen given the dynamics of our society right now and where things are headed is dangerously naive.

You say you anticipate you will be labeled a racist or a white supremacist for calling attention to the anti-white racism issue. You also relate that some colleagues even told you the book was a great idea but thought it would be better if a non-white person wrote it. Are you truly prepared for backlash?

Yeah. You know, this should be the life that you should sign up for if you’re going to be a political person in a serious way. Margaret Thatcher had a quote where she said she sort of loved the attacks by her enemies and the virulence of them, even for years after she left office, because it showed that she’d done something rather than just that she’d been someone.

So I kind of welcome it at a certain level. You always worry about your family and bystanders getting involved. But I’m ready for that. I feel very comfortable in what I’ve done. I feel very comfortable about my thesis. I haven’t tried to overstate it. I haven’t tried to be more dramatic than what the facts show.

I think, at the end of the day, it comes down to that it’s not what they call you, it’s what you answer to. I’m going to try to tune out the naysayers and just put my thesis out there and hopefully folks will … embrace it.

Note: Answers and questions from the video interview may have been edited and condensed to remove random utterances, such as pauses or filler words that are a part of speech, and for brevity and clarity.