President Joe Biden’s White House recently delivered to Congress its “Mid-Session Review” of the federal budget. The bottom line in this late July document was bad: The deficit for 2024 is projected to be $1.87 trillion and the nation likely will be $37 trillion in debt by the end of the year.

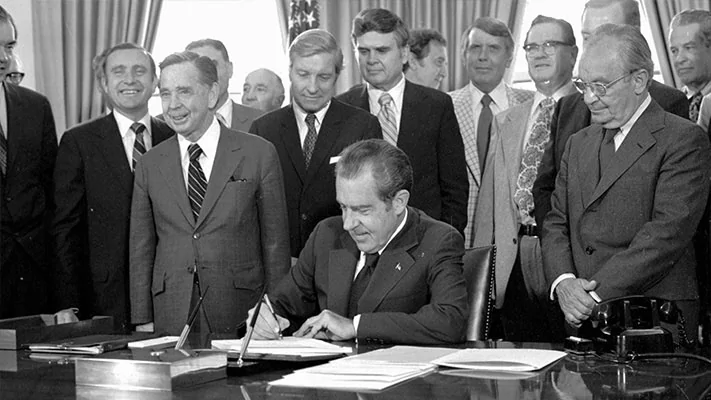

This news arrived just one week after the 50th birthday of the law that created the congressional budget process. President Richard M. Nixon hailed the Control Budget and Impoundment Act’s passage in his July 12, 1974 signing statement.

“I commend the Congress for this landmark legislation,” Nixon said. “… This bill will allow the Congress to step up to full and equal responsibility for controlling Federal expenditures.”

The law significantly upgraded Congress’s procedures for taxing and spending. Hitherto, as Nixon observed, Congress would pass spending bills with “no system for establishing priorities relating to an overall spending goal.” That made for lots of red ink.

The 1974 act tried to fix that by binding Congress to a rational process. The president would submit his proposed budget in February. Congress would review it and utilize revenues and expenditures estimates from the newly created Congressional Budget Office. The chambers would then pass a budget resolution in April to set spending levels for the government. Legislators subsequently would enact spending legislation whose costs fell within the figures set in the resolution by Sept. 30. Midway through the year, the president would submit his midyear review, and Congress could use a fast-track reconciliation process to adjust spending and taxes to shift economic forecasts.

The process worked decently for a few years before troubles began. Presidents were often late to submit their budgets and treated them more as messaging documents than serious opening bids in their negotiations with Congress. Presidents regularly treat budget reconciliation as a means for forcing through partisan policies, such as the Biden administration’s budget-busting Inflation Reduction Act of 2022, that would be thwarted by a Senate filibuster.

Legislators have done no better. They often approve budget resolutions loaded with unrealistic assumptions. Former Rep. David Obey, who was chairman of the House Appropriations Committee for two stints, groused in 1982: “The only kind of budget resolution you can pass today is one that lies. … You cannot get members under the existing system to face up to what the real numbers do. You always end up having phony economic assumptions and all kinds of phony numbers on estimating.” Some years, Congress does not even bother to adopt a budget. Legislators regularly appropriate money whether the money has previously been authorized by law, as the budget process requires — or not. Or they approve additional spending under “emergency” supplemental acts.

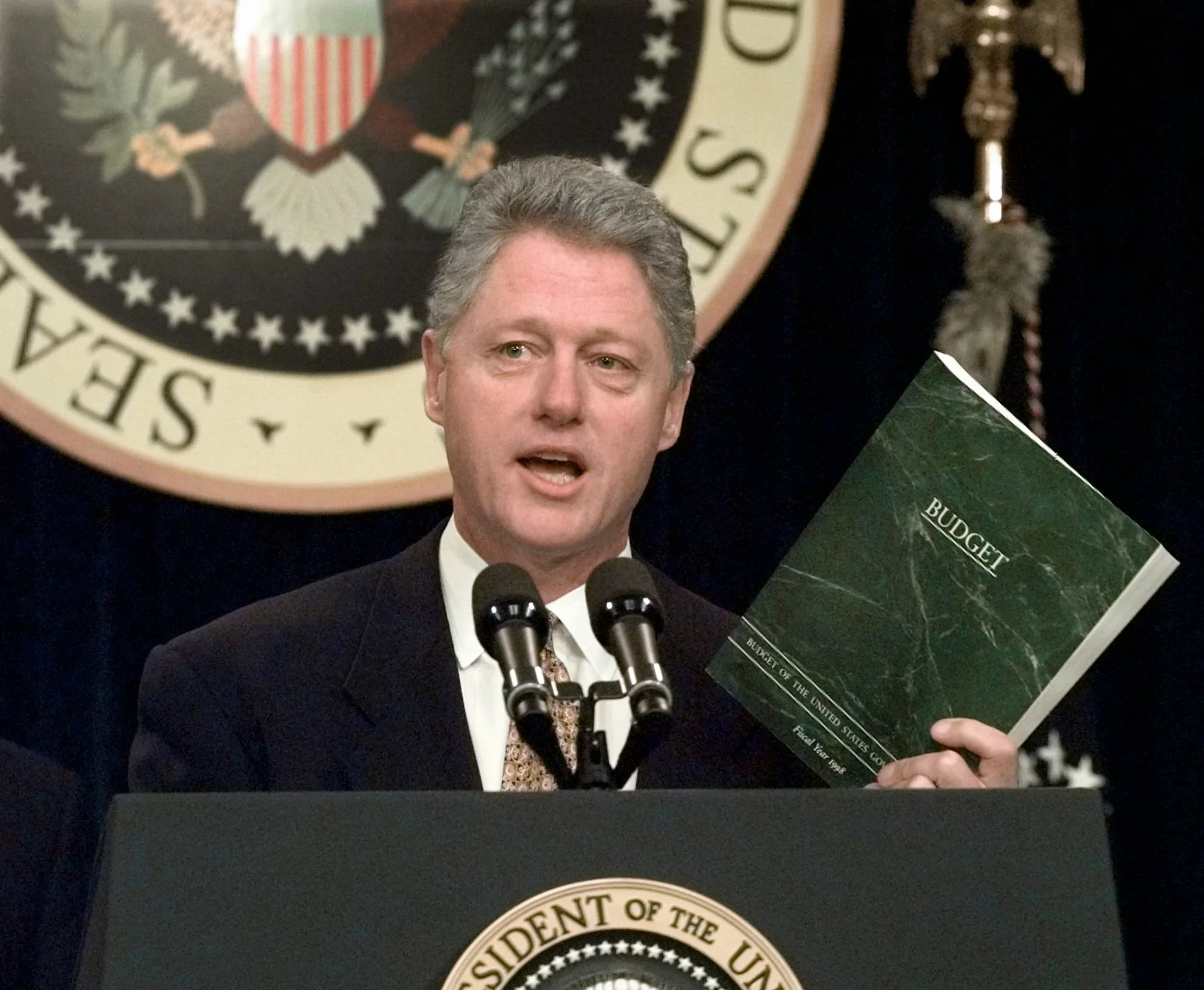

The last time the president and Congress followed the CBA was in 1997 when a Republican-led Congress and Democratic President Bill Clinton agreed on a budget that produced a surplus — the first of four straight black ink years before sinking deeply back into the red. Since then, legislators have annually voted to increase deficits by cutting taxes and increasing spending. This year, the House enacted only five of the 12 spending bills and the Senate has passed none. Both chambers are out of session until Sept. 9.

So why did such a well-thought-out process go wrong? Opinions vary.

Critics often point to the budget process itself. They argue that the act demands a lot of rapid agreement among disputatious legislators in a short amount of time. They also say the CBA largely sidelined the president from the process. “The president has to provide a safe harbor, so to speak, for Congress, for Congress to make tough decisions,” observed Allen Schick, an emeritus professor at the University of Maryland and budget scholar who helped write the CBA. Only the chief executive can use the bully pulpit to persuade the public.

The CBA’s approach to Medicare and other entitlement programs also is problematic. “If the purpose of the budget process is to set up a comprehensive process to help Congress set priorities and trade off all spending and taxes, then its treatment of entitlement costs fails that standard,” notes Brian Riedl, a budget policy expert at the Manhattan Institute. “Discretionary spending must be re-appropriated from scratch every year. But lawmakers can do nothing and entitlement costs will expand as much as 7% annually.”

CLICK HERE TO READ MORE FROM THE WASHINGTON EXAMINER

Others blame the people and the culture on Capitol Hill. Veronique de Rugy, a senior fellow in political economy at the Mercatus Center, told the Washington Examiner the 1974 act “only works to the extent that [legislators] … believe it is wrong to break the law.” Until the mid-20th century, legislators mostly shared a belief in balancing the budget. They would run deficits during national crises, such as the Great Depression, but afterward would cut spending and raise taxes to restore fiscal balance.

Whether it is the process or the people, the public is distressed. Gallup found 77% of people said they worried about our nation’s red ink “a great deal” or “a fair amount.” This is unsurprising: They and their descendants are on the hook for the $37 trillion in debt.

Kevin R. Kosar (@kevinrkosar) is a senior fellow at the American Enterprise Institute and edits UnderstandingCongress.org.