Labour’s Keir Starmer has won the British election, raising questions about the next chapter in the “special relationship” between the United States and the United Kingdom. For all the talk of these ties between British prime ministers and American presidents, the truth is, it’s a pretty recent invention. Throughout America’s first century, England was seen more as an adversary or a rival. Not until the tumult of the 20th century would Britain be considered an ally.

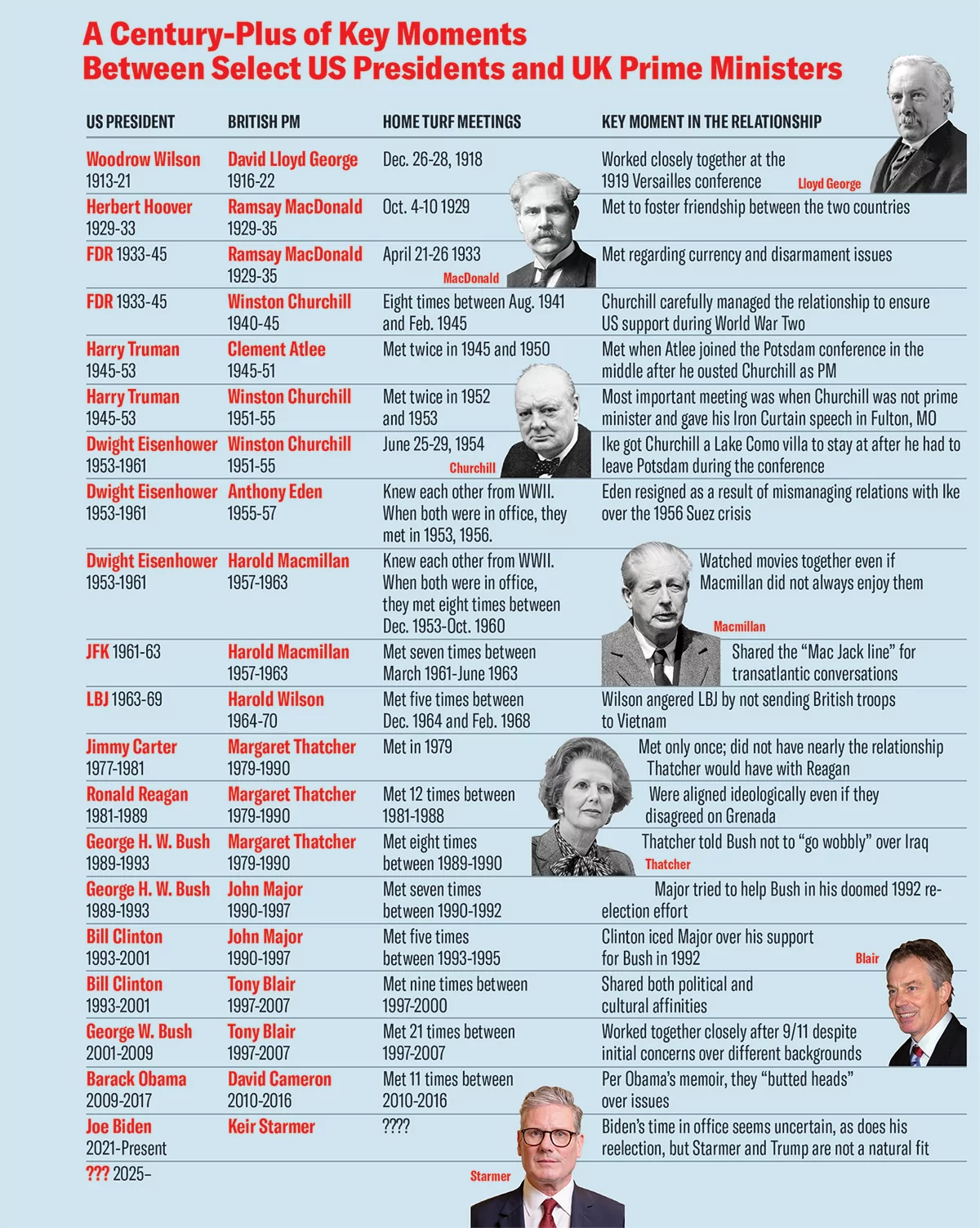

Woodrow Wilson was the first sitting president to meet a sitting British prime minister, his World War I ally David Lloyd George. Wilson was also the first president to visit the British Empire as president, in England in late December of 1918. Wilson was his typical antisocial self, saying at a Buckingham Palace state banquet, “You must not speak of us who come over here as cousins, still less as brothers. We are neither. Neither must you think of us as Anglo-Saxons, for that term can no longer be rightly applied to the people of the United States.” Despite this odd beginning, the two men met frequently at the Versailles peace conference in 1919. They, along with France’s Georges Clemenceau and Italy’s Vittorio Orlando, met perhaps as many as 145 times as they attempted to sort out the shape of the world following the Allied victory — and did a pretty poor job of it in the process.

Ramsay MacDonald was the first prime minister to meet multiple U.S. presidents. MacDonald, who had served briefly in 1924, met his presidents in his longer stint, from 1929 to 1935. He met Herbert Hoover in 1929 and then later met Franklin Delano Roosevelt in 1933. The White House press release on the Hoover visit said the meeting “had as its chief purpose the making of personal contacts which will be fruitful in promoting friendly and frank relations between the two countries.” When MacDonald met Roosevelt four years later, things were far more serious, as the Great Depression had already started, and the conversation was focused on both the World Economic Conference as well as what Roosevelt called the “need for making further progress toward practical disarmament.”

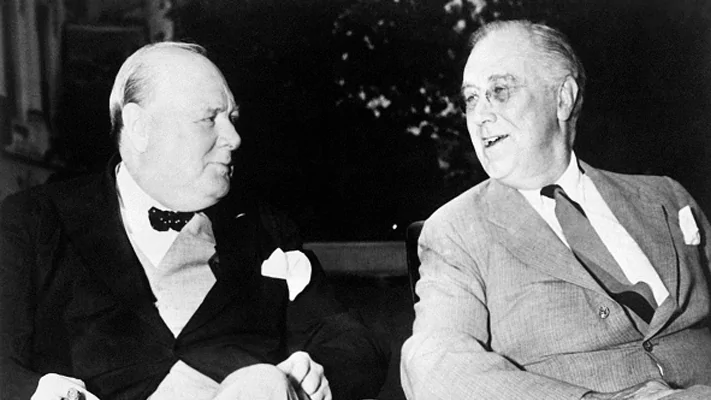

The disarmament effort did not work out. England was at war with Germany the next time a prime minister met with an American president in August of 1941. The entry of the U.S. into the war came a few months later, following Pearl Harbor, and Winston Churchill did not waste much time in coming to see Roosevelt again, this time in the White House. The journey itself took 10 days. Churchill crossed the Atlantic by ship, a risky move given the wolf packs of German U-boats going after allied shipping, and then flew to Washington. Over the next 23 days, Churchill’s goal was to make sure that the U.S. was not exclusively focused on fighting the Japanese instead of the Germans. He knew he needed Roosevelt’s support in the war effort and tended to their relationship carefully, recalling after the war that “no lover ever studied every whim of his mistress as I did those of President Roosevelt.”

At one point during the Christmas trip, Roosevelt walked in on Churchill naked, prompting Churchill to say, “You see, Mr. President, I have nothing to hide from you.” They would also stay up late talking into the night. Churchill would sleep late, but Roosevelt would be working at his desk early the next morning, making him so exhausted from Churchill’s visits that he would often have to go to his home at Hyde Park afterward to recuperate. Unsurprisingly, Eleanor Roosevelt was not a fan of Churchill or his visits.

The Christmas visit was the best known of Churchill’s six visits with Roosevelt in the U.S. He also met with Roosevelt in Malta and Argentia, Newfoundland, both parts of the British Empire, as well as had summits with both Roosevelt and Josef Stalin in Tehran in 1943 and Yalta in 1945, part of a total of 113 days the two men spent with each other.

When the leaders of the allied powers met again in Potsdam in July of 1945, Harry Truman had replaced the recently passed Roosevelt. And Churchill left in the middle of the conference after being defeated by Clement Attlee in an election that took place during Potsdam. Churchill literally had to pack his bags and depart, an embarrassing moment only slightly alleviated by a gracious Gen. Dwight Eisenhower securing a villa on Lake Como for Churchill to go to. The switch meant that Truman met not one but two prime ministers at this one conference.

Truman would meet Churchill at least three more times. Two of those interactions took place after Churchill regained the office of prime minister in 1951. But the more famous visit took place during the interregnum between Churchill’s stints as prime minister. In early 1946, Westminster College invited Churchill to speak at its campus in Fulton, Missouri. The invitation included an unusual note at the bottom, from Truman, who wrote, “This is a wonderful school in my home state. If you come, I will introduce you. Hope you can do it.” Churchill accepted and Truman lived up to his word, not only attending Churchill’s March 5, 1946, speech but also traveling there with him. Churchill called the speech Sinews of Peace, but no one refers to it by that name. It has become known as the “Iron Curtain” speech, after Churchill’s famous line: “From Stettin in the Baltic, to Trieste in the Adriatic, an iron curtain has descended across the continent.”

The speech got some blowback at the time for its bellicosity. One of the critics was Eleanor Roosevelt, who still did not like Churchill dating back to his late-night gabfests with her late husband. Truman also initially distanced himself from the speech but eventually came around. The speech was extremely important in setting forth the parameters for a close relationship between presidents and prime ministers in the post-World War II world. It set the lines of the battle between the Western democracies and the Soviet Union and its satellite nations. It also saw Anglo-American cooperation as central to the Western response. The gifted wordsmith Churchill also coined the phrase the “special relationship” between the U.S. and Britain in that speech, establishing a paradigm no one would have thought possible when British troops were burning the White House during the War of 1812. Churchill’s words were prescient, as the Anglo-American relationship remained at the heart of the Cold War alliance that defeated the Soviet bloc in the Cold War and would keep prime ministers and presidents closely tied together for the ensuing six decades.

Truman’s successor, Eisenhower, met three British prime ministers, Churchill, Anthony Eden, and Harold Macmillan, more than 10 times in his two terms as president. Eden lost his job in part because of poor relations with Eisenhower. In the fall of 1956, Britain and France joined with Israel in attacking Egypt after Egypt blocked access to the Suez Canal. While Israel successfully conquered the Sinai Peninsula, the war was a political victory for Egypt because Eisenhower was irate over the invasion and had the U.S. join a condemnation of the action in the United Nations. Israel was forced to return Sinai, and Eden resigned as prime minister over the incident.

Macmillan, Eden’s replacement, did not make the same mistake of failing to maintain strong ties with the president. He knew Eisenhower during World War II and worked to maintain the friendship when both men were in power. In March of 1959, Macmillan visited Eisenhower at his farm in Gettysburg. They watched a movie together after dinner, but the movie was decidedly not to Macmillan’s liking. Macmillan wrote in his diary that it was called “the great country or some such name,” that “it lasted three hours,” and that “it was inconceivably banal.” Ike apparently disagreed. He watched the Gregory Peck-starring The Big Country four times as president.

More importantly, Eisenhower visited Macmillan in London in the summer of 1960. This was the first visit by an American president to London since Wilson’s visit nearly half a century earlier. The visit was good for Macmillan politically, and he won reelection that October. For his part, Eisenhower was unimpressed with the seat of British power, finding No. 10 Downing St. “rather ancient.”

Thanks to their friendship, Macmillan was comfortable speaking frankly with Eisenhower. When Vice President Richard Nixon looked sweaty and beset by a 5 o’clock shadow in his 1960 presidential debate against challenger John F. Kennedy, Macmillan told Eisenhower in New York that “your chap’s beat.” When Eisenhower asked for clarification, Macmillan told him, “One of them looked like a convicted criminal and the other looked like a rather engaging undergraduate.”

Macmillan’s closeness with Eisenhower did not preclude Macmillan from befriending Kennedy after the 1960 election. The two men had a dedicated phone line for communicating with each other, referred to as the “Mac-Jack line.” They were more than two decades apart, but they had a genuine affection for each other. After Kennedy performed poorly at a 1961 meeting with Soviet leader Nikita Khrushchev in Vienna, he went to visit Macmillan, who consoled the younger man with “some sandwiches and whiskey.” Later, Kennedy recalled, “I feel at home with Macmillan because I can share my loneliness with him.”

Kennedy’s successor, Lyndon Johnson, did not have as much luck at No. 10 Downing St. He and Labour Party Prime Minister Harold Wilson disagreed about Vietnam, especially over Wilson’s refusal to contribute British troops to the American effort there. Wilson once joked after a call with Johnson that “Lyndon Johnson is begging me even to send a bagpipe band to Vietnam.”

As the Vietnam incident shows, while the two countries were allies in the Cold War, disagreement over specific policies could cause tensions between their leaders. This could be the case even when the president and prime minister themselves had a special relationship. Ronald Reagan met Margaret Thatcher in 1975 before either of them had attained their countries’ highest positions. Reagan sent her a follow-up note in which he told her that she had “an enthusiastic supporter out here in the ‘colonies.’” When she became prime minister in 1979, Jimmy Carter was president, but the two did not share a bond, and she only went to the White House once during the Carter years.

Once Reagan came to power, he and Thatcher had what she referred to as “almost identical beliefs,” especially when it came to free market economics and the Cold War. She saw the U.S. and Great Britain as geostrategically aligned and even said of the U.S., “Your problems will be as our problems, and when you look for friends, we shall be there.”

Still, the two could and did disagree, most notably when it came to America’s 1983 invasion of Grenada, which, while independent, was a member of the British Commonwealth. Thatcher was angry and humiliated about not getting an advance warning, for which Reagan later apologized.

Thatcher was also instrumental in helping to bring about an end to the Cold War. She recognized earlier than Reagan that Soviet leader Mikhail Gorbachev was different, telling Reagan that Gorbachev was “a man who you can do business with.” Thatcher also encouraged Reagan’s successor, George H.W. Bush, to take a strong stance against Iraqi dictator Saddam Hussein’s invasion of Kuwait in 1990. She told him in an Aug. 26 phone call that “this was no time to go wobbly.” Bush didn’t, and he worked with her to build an international coalition that expelled Iraq from Kuwait.

Thatcher’s successor, John Major, was less deft. While he was close to Bush, he made the mistake of being too open in his support for Bush in his 1992 reelection effort, including allowing for a search for damaging information stemming from Bill Clinton’s time at Oxford University in the 1960s. Clinton was none too happy about this and made sure Major knew it. For the first scheduled call between the two, Clinton ghosted Major, making the Brit wait for 45 minutes until Major finally hung up the phone in frustration, saying, “This is ridiculous.” When the Situation Room staffers went up to the Oval Office to tell Clinton that Major had finally dropped the line, they found that Clinton had left the White House to play golf. As Situation Room director Jim Reed recalled of the incident, “I thought it was a pretty good way of sending a message to a foreign leader: Don’t mess with me.”

Clinton got along better with Tony Blair. Both Clinton and Blair were children of the 1960s who ended eras of conservative governance by making their leftist parties appear more centrist. When Clinton left, though, the very reasons for their camaraderie made Clinton’s successor, George W. Bush, nervous about how he and Blair, from opposite sides of the ideological spectrum, might get along. At their first summit, at Camp David less than a month after Bush’s inauguration, a reporter asked Bush what they had in common. Bush’s humorous but less than encouraging response: “Well, we both use Colgate toothpaste.” Fortunately, the two men bonded behind the scenes. After dinner, the leaders and their wives discussed watching a movie together and were able to find common ground that way. As Bush wrote in his memoir, “When they agreed on Meet the Parents, a comedy starring Robert De Niro and Ben Stiller, Laura and I knew the Bushes and Blairs would get along.”

The closeness between the two men would become important seven months later, when the U.S. was attacked by al Qaeda terrorists on 9/11. Blair became a key partner of Bush in the ensuing war on terrorism and even allied with Bush on the invasion of Iraq, which gave Bush important cover for the move on the world stage.

In recent years, turnover at the top on both sides of the Atlantic has limited the ability to build strong bonds between presidents and prime ministers. The last president and prime minister to have a sustained relationship were David Cameron and Barack Obama, but while the relationship was sustained, it was not strong. Cameron was from the Conservative Party, and it has become increasingly difficult in our polarized environment to maintain good relationships across the ideological divide. Obama acknowledged in his memoir that he and Cameron “butted heads,” as Obama felt that Cameron was cozying up too much to China, while Cameron felt left out as Obama looked more to Germany’s Angela Merkel rather than Cameron for leadership in Europe.

Starmer’s victory on July 4 raises the prospect of this ideological divide playing out once again, to the detriment of the “special relationship.” Former President Donald Trump is leading in the polls over a weakened President Joe Biden, who has been getting blistered on both sides of the aisle for his poor debate performance and growing senescence. Should Trump win, he and Starmer will have numerous ideological differences to navigate. Starmer is far less aligned with Israel than Trump is — and is even less than Biden is. Starmer also does not have a relationship with Biden at the moment, although he tried to meet with him. He is a Biden fan and supporter of Biden’s economic policies.

CLICK HERE TO READ MORE FROM THE WASHINGTON EXAMINER

Starmer, to his credit, has been saying the right things, including that he will “work with whoever is elected president.” According to Starmer, “We have a special relationship with the U.S. that transcends whoever the president is.” But it won’t be easy. Referring to Trump’s legal troubles, Starmer noted that “it is an unprecedented situation. There is no doubt about that.” Worse, his new foreign secretary, David Lammy, is a friend of Obama who has called Trump a “racist KKK and Nazi sympathizer” and protested Trump’s 2018 state visit to the U.K. Lammy has tried to walk back his hostility, characterizing Trump as “often misunderstood” and trying to meet with Trump allies to build the ties he would need should he become foreign secretary in a Starmer government. Lammy has met with Trump allies Chris LaCivita, Mike Pompeo, and Robert O’Brien, as well as Republican members of Congress such as Sens. J.D. Vance (R-OH), Lindsey Graham (R-SC), Jim Risch (R-ID), and Thom Tillis (R-NC). Even with all these efforts, he’s unlikely to be aligned with a Trump foreign policy.

While the personal touch is nice, it may not be enough. The special relationship has existed for almost a century, but as this history shows, it did not exist before the 20th century, and it may not continue throughout the rest of the 21st.

Washington Examiner contributing writer Tevi Troy is a senior fellow at the Bipartisan Policy Center and a former senior White House aide. He is the author of five books on the presidency, including the forthcoming The Power and the Money: The Epic Clashes Between Commanders in Chief and Titans of Industry.