President-elect Donald Trump has been dreaming about aggressive trade policy for decades, and in a second term, he’ll see just how far that vision can take him.

In fact, Trump got the game going even before the term started by threatening 25% tariffs on Canada and Mexico unless they fix their “ridiculous Open Borders.” It’s part of an incoming administration-wide view of tariffs as a multifaceted tool that can do everything from boosting domestic manufacturing to stopping illegal immigration to ending foreign wars.

“The most beautiful word in the dictionary is tariff,” Trump told the Economic Club of Chicago during a campaign stop. “It’s my favorite word. It needs a public relations firm to help it, but to me, it’s the most beautiful word.”

The reason tariff needs a public relations firm, to use Trump’s phrase, is that the word sends a jolt of fear down the spine of economists who say import duties will raise prices and cause foreign nations to retaliate in an escalatory trade war.

“We haven’t had a good track record with it,” said Jared Pincin, an economics professor at Cedarville University in Ohio. “We’ve had steel tariffs on and off since the early 1960s and it hasn’t brought back steel manufacturing in the U.S. The major problem is, what are the other countries going to do?”

If those other countries raise their tariffs, everyone loses, the thinking goes.

However, as a negotiating tactic, Pincin sees the value.

“He’s following a lot of the same script from his first term, where he’s using tariffs as a bargaining chip,” Pincin said. “We saw it with the Canada and Mexico tariff threats. Within hours, both the Canadian prime minister and the Mexican president were in contact with him. So that’s part of his negotiating strategy.”

Trump has been known for decades as a man who throws out extreme proposals as a way to bring people to the table, and he’s been talking about tariffs for almost as long. In a 1988 appearance on The Oprah Winfrey Show, Trump complained that Japan was dumping electronics into the U.S. market while making it impossible to import U.S. products.

“A negotiating tactic and way to gain leverage applies not just to Trump’s trade policy proposals, but to just about everything else he has floated or threatened,” said Gwenda Blair, who wrote a biography on Trump in 2000. “Plus, of course, [it’s to] his own financial advantage.”

However, there are true believers in Trumpworld, such as Robert Lighthizer, Trump’s first-term trade representative and author of the 2023 book, “No Trade Is Free.”

Lighthizer grew up in an Ohio port town that was decimated by the offshoring of steel manufacturing in the late 20th century. He has been pushing for fair trade since the Reagan administration and said the topic is something Trump thinks about every single day.

“For President Trump, issues of international trade were a key priority that dominated his thoughts,” Lighthizer wrote. “I quickly came to know the depth of his level of engagement firsthand when I assumed my role as U.S. trade representative.”

Trump will also have more support in the vice president’s office thanks to the ascension of Vice President-elect J.D. Vance (R-OH), who, like Lighthizer, grew up in an Ohio town that was decimated by the decline of the steel industry.

Vance’s biggest asset may be smoothing relationships in the Senate, where Trump might meet resistance from old-school free trade purists in the upper chamber.

“Vance would, I believe, take a keener interest in manufacturing, especially those industries most affected in Ohio and other Rust Belt states,” said Marc Clauson, a Cedarville University history professor.

While Trump has no personal Rust Belt history to pull from, his views may stem from when well-heeled Japanese firms began buying up trophy New York City real estate in the 1980s, including the Exxon building in 1986 and Rockefeller Center in 1989. Trump may have seen such moves as a threat to his real estate empire, sparking his interest in foreign relations.

The second Trump administration will likely include more like-minded thinkers.

Trump’s first-term treasury secretary, Steven Mnuchin, was sometimes a reluctant player in the tariff game. However, if confirmed, new Treasury leader Scott Bessent will be more on board and has argued that tariffs will not cause inflation.

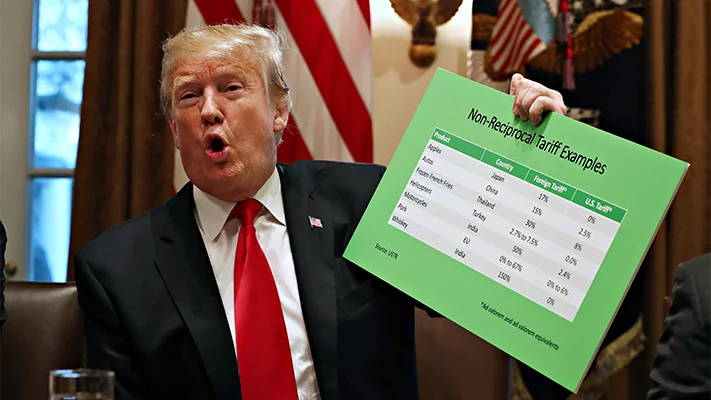

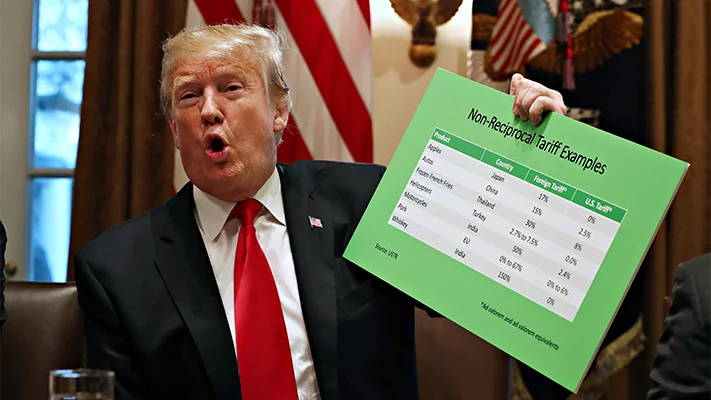

Trump and allies aren’t skeptical of free trade per se, but they say foreign countries aren’t actually practicing it, leaving the United States behind or, as Trump would put it, “getting ripped off.”

For example, the U.S. imposes 2.5% tariffs on European automobiles while Europe imposes 10% tariffs on American cars. The European Union imposes tariffs of up to 26% on wine imports, while wine coming into the U.S. is tariffed at less than 1%.

One of Trump’s big first-term battles with Canada was over its dairy industry tariffs, which were set as high as 300% to keep products from American farmers out of the country.

Trump cut several trade deals during his first four years, renegotiating NAFTA, signing the Phase One agreement with China, and reaching a new trade policy with South Korea. The Biden administration largely kept Trump’s China tariffs in place but was much less active in the trade space overall.

Paul Sracic, an Ohio-based adjunct fellow at the Hudson Institute, agreed that Trump sees tariffs mostly as a negotiating tool toward reaching deals with foreign nations rather than something he will implement at scale.

“It’s sort of like playing poker,” he said. “You’ve got to bluff, and it’s got to be a bluff that the other side accepts. That’s why I think Trump is so firm on this when he talks about 20% tariffs. You have to make it sound as if it’s a real, viable threat, and you have to be willing to follow through on your threat if you don’t get what you want.”

Of course, if Trump doesn’t impose big tariffs, it will undercut some of his other proposals, such as using revenue from tariffs to offset spending deficits or cut taxes.

CLICK HERE TO READ MORE FROM THE WASHINGTON EXAMINER

On the whole, Sraric expects Trump’s second-term trade policy to be similar to his first, only on an accelerated timeline given his greater experience in Washington and a more tariff-friendly team working under him.

“It’s always a transactional thing with Trump,” Sracic said. “This is negotiation. He says he’s thrilled about putting tariffs in, says he’s the tariff man. But then you see what happens, and it’s always tied to something like fentanyl trafficking or immigration. It’s always, ‘This is my threat if you don’t do what I want you to do.’”

Haisten Willis is a White House reporter for the Washington Examiner.