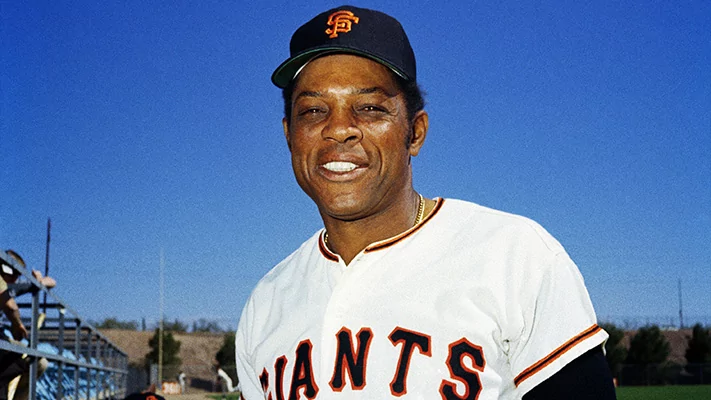

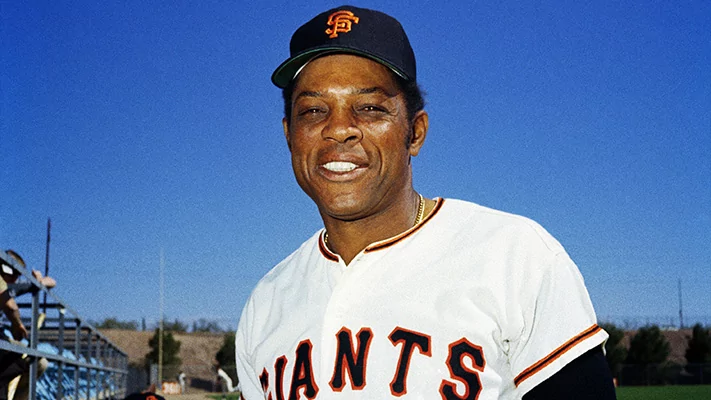

We are for the most part not blessed to live in the era of giants. The greatest of all times in their fields — Michelangelo in sculpture, Shakespeare in drama, Homer (or Dante) in poetry, Raphael in painting, Beethoven in music — all lived hundreds (and in some cases thousands) of years ago. Long gone are the days of the preeminent political leaders such as Washington, Lincoln, and Churchill as well. But professional sports is a domain that is still new enough to have allowed some of us to glimpse its legends in our lifetimes. One of these truly transcendent greats, Willie Mays, took his leave from us on June 18 at the age of 93.

A Giant on the field, and a giant of his sport, Willie Mays was considered by many to have been the greatest baseball player to have ever lived. Ted Williams may have been a better pure hitter, Babe Ruth may have had more power, Rickey Henderson may have been a better base runner, Ozzie Smith may have been a better defender, and Roberto Clemente may have had a better arm. But no one combined all of these five essential baseball skills into a more complete and exquisite mixture than Mays, making him the epitome of the five-tool player. For this reason, the past four generations of kids who grew up playing baseball in their backyards all knew that for as cool as Ken Griffey Jr. or Reggie Jackson or even Mickey Mantle may have been, if there was one player you wanted to model your game after, it was Willie Mays.

Willie Howard Mays Jr. was born on May 6, 1931, in Westfield, Alabama. A superior athlete in his youth who was a star high school football, basketball, and baseball player, Mays began his baseball career at the age of 17 in 1948 in the Negro leagues with the Birmingham Black Barons. After hitting over .300 for two seasons and helping lead the Barons to a Negro League World Series, the New York Giants signed Mays in 1950. Mays moved rapidly through the Giants’ minor league system, and by the following year Mays was called up to the majors, where his powerful bat helped him win the National League Rookie of the Year and also helped the Giants win the National League pennant. The next several years of Mays’s career would be interrupted by military service. By the time he returned in 1954, Mays doubled his 1951 home run output, raised his batting average by over 70 points, and won the first of his two National League Most Valuable Player awards.

CLICK HERE TO READ MORE FROM THE WASHINGTON EXAMINER

In a sport in which numbers have always been the most valuable currency, Mays accumulated more riches than just about any other player in the history of the game: 24 All-Star Game appearances (one behind Hank Aaron for most all time), 12 Gold Glove Awards (tied with Roberto Clemente for most all time for an outfielder), 660 home runs (third place all time when he retired), one batting title, four stolen base titles, four home run titles, two 30-30 (30 stolen bases and 30 home runs) seasons, and a 300-300 (300 stolen bases and 300 home runs) career (the first to ever accomplish that feat).

But numbers alone do not tell the story of Mays’s career. There was a wonder, joy, and sense of magic to the way he played, which, far more than the gaudy stats, accounts for the hold he’s had on a half-century of fans. Mays’s unique brew of athletic wonder and baseball magic was encapsulated in one of the most famous plays in American sports history. Certain sports legends’ career-defining moments are so well known that we need no more than two words to conjure them: Michael Jordan had “The Shot,” John Elway had “The Drive,” both Larry Bird and John Havlicek had “the steal,” and Willie Mays had “The Catch.” In Game 1 of the 1954 World Series, Cleveland’s Vic Wertz hit a long line drive into deep center field that seemed destined to be a stand-up double, maybe even a triple. But Mays, who had been tracking the ball the instant it catapulted off the bat, sprinted backward and, seconds before crashing into the outfield wall, stretched out his glove, caught the ball over his left shoulder, heaved the ball back toward the infield, and spun 360 degrees to avoid hurtling into the fence. Mays’s spectacular play propelled the underdog Giants to a Game 1 win and a 4-0 World Series victory — and earned the so-called Say Hey Kid a permanent place in the American cultural pantheon.

Daniel Ross Goodman is a Washington Examiner contributing writer and a postdoctoral fellow at Harvard Divinity School. His latest book, Soloveitchik’s Children: Irving Greenberg, David Hartman, Jonathan Sacks, and the Future of Jewish Theology in America, was published last summer by the University of Alabama Press.