Conservatives have long had their sights set on revisiting a Supreme Court case that set a high bar for public officials to prove the media defamed them, but President Donald Trump’s return to power has put a spotlight on this key press protection.

The Right’s interest in changing the New York Times v. Sullivan precedent gained traction after Trump went to war with the media during his 2016 campaign and as polls showed trust in news outlets declining.

Now, Trump’s latest round of legal fights with a slate of news organizations have led some experts to argue that the libel ruling, which helps shield journalists from lawsuits about their reporting, is more necessary than ever.

Others, meanwhile, suggest the president’s media-averse posture only bolsters their position that the Supreme Court should overturn the landmark case.

‘What they do is illegal’

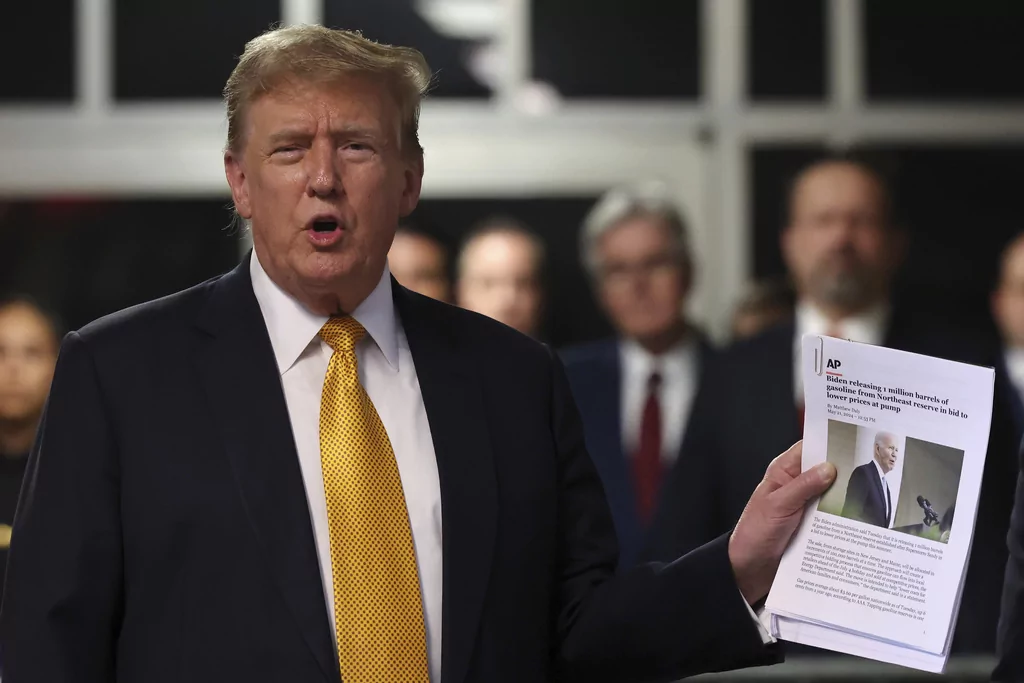

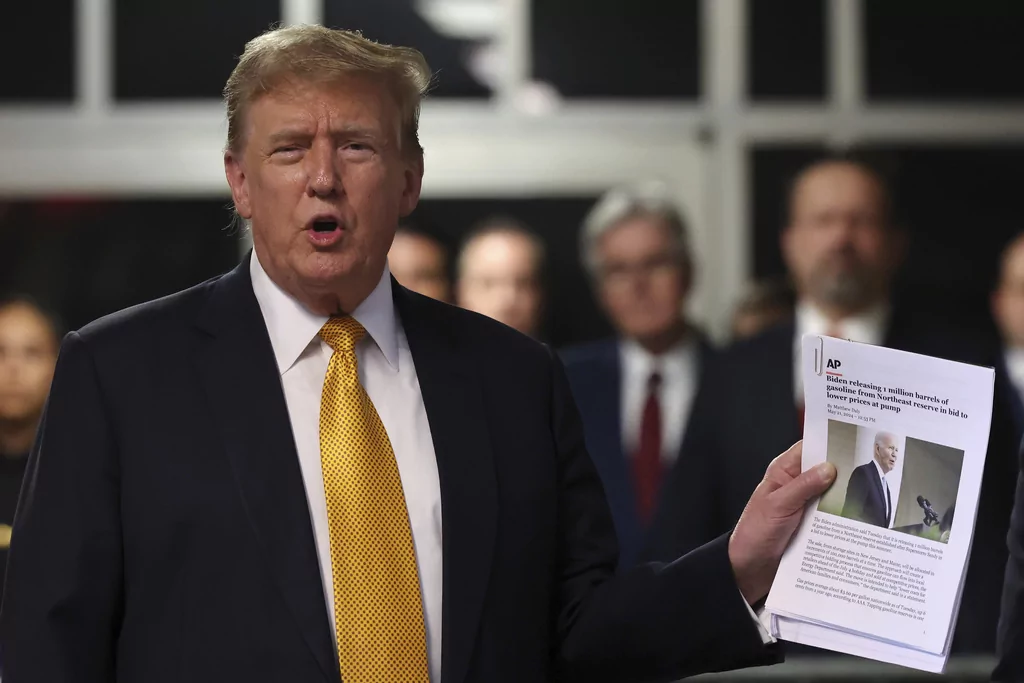

Presidents airing grievances about the media is common, but Trump stands out as one of the most combative and litigious of any in recent history.

In a rare speech at the Department of Justice last month, Trump sniped at “these networks and these newspapers,” saying they were “no different than a highly paid political operative” and that “what they do is illegal.”

In February, he warned in a Truth Social post that he plans to sue more book publishers and media outlets to “find out” if their anonymous sources “even exist,” and he suggested Congress pass a “NICE NEW LAW” to combat defamation.

Trump’s fury with the press coincides with a Gallup survey showing distrust in the news media on a steady, decadeslong incline.

But the survey also shows Democrats’ trust in the media sharply rising and Republicans’ sharply dropping in 2016, in the heat of Trump’s successful campaign, in which he defied nearly every poll and defeated Hillary Clinton. Longtime media reporter Dylan Byers dubbed Trump the “media king” at the end of 2015, observing how the press fixated on Trump, a bombastic real estate magnate and reality show host, while ignoring his primary competitors.

The more attention he gained from news outlets, the more Trump clashed with them, calling them “scum” on the campaign trail and vowing in 2016 to make it easier for them to face lawsuits.

“I’m going to open our libel laws, so when they write purposely negative and horrible and false articles, we can sue them and win lots of money,” Trump said to loud applause. “We’re gonna open up those libel laws.”

Building momentum to weaken libel protection

Heightened scrutiny of New York Times v. Sullivan only began in recent years. Trump’s early rally cries about suing the media jumpstarted it, but his appointee, Supreme Court Justice Clarence Thomas, made the prospect of reconsidering it more serious.

While the conversation began with Trump in 2016, John Shu, a legal scholar who served in both Bush administrations, said Thomas “certainly opened the door on that” in a concurring opinion the justice wrote in 2019.

“He’s been suspicious of Sullivan, not because of what he’s been through personally, but because it lacks basis in the text and original understanding of the First Amendment,” Shu told the Washington Examiner. Thomas has long been the subject of media coverage about gifts he received from billionaire Republican donor Harlan Crow.

Thomas first criticized New York Times v. Sullivan in a concurrence in a case against Bill Cosby, calling the ruling and subsequent expansions of it “policy-driven decisions masquerading as constitutional law.” Justice Neil Gorsuch, a Trump appointee, later followed suit, signaling a ripening scenario for lowering the libel bar.

The unanimous decision in 1964 arose from L.B. Sullivan, an official in Montgomery, Alabama, suing the New York Times for libel after it published an inaccurate advertisement that criticized how police treated civil rights protesters.

The Supreme Court sided with the newspaper and, in doing so, set the “actual malice” standard: a public official must prove a media outlet knowingly published false information or showed “reckless disregard for the truth” when it published the falsehood. The courts expanded the standard in later years, including by applying it not just to public officials but also to public figures.

Attorney Libby Locke, who represented Dominion Voting Systems in a defamation lawsuit in which it secured a $787 million settlement with Fox News, said in a panel last month at the Heritage Foundation that the case for reconsidering New York Times v. Sullivan is “stronger than ever” and that the media is far too insulated.

She said she had deemed the ruling “suspect” years ago. However, that was also “a Hunter Biden laptop ago, it was a Russia-gate hoax ago, it was a ‘two weeks to flatten the curve’ ago, and it was ‘multiple assassination attempts against the now president and a current U.S. Supreme Court Justice’ ago,” Locke said, citing recent incidents that triggered media criticism from the Right.

Locke said that as a plaintiff-side defamation lawyer, she witnesses the “brazenness with which journalists today, cloaked in Sullivan immunity, go about their job.”

The Trump factor

Trump has repeatedly threatened news outlets and reporters with legal action and sometimes delivered on his promise, albeit mostly unsuccessfully. In the past year alone, he settled a defamation lawsuit with ABC News and used a novel legal strategy to sue the Des Moines Register and Iowa pollster Ann Selzer over a polling flop and CBS over its editing of a 60 Minutes interview with former Vice President Kamala Harris. Those cases remain pending.

Ronnie London, general counsel at the Foundation for Individual Rights and Expression, told the Washington Examiner his group is working on “a number of cases where little guys, just individual people who went out and spoke on matters of public concern, have been sued.”

London said the “most obvious one” was Selzer, whom FIRE is representing. He quipped that she was not quite little since she had been the “queen of Iowa polling for decades.” Selzer retired after her bombshell poll showing Trump losing women voters ahead of the 2024 election missed by a wide margin.

“Do we need a very strong standard to protect erroneous statement in making political predictions and in political speech? I’m looking at Donald Trump, relatively powerful guy, right, suing Ann Selzer. I’m thinking, yeah, we do need a strong standard,” London said.

London did not limit his concern to Trump and pointed to both the broader administration’s adverse actions toward media, such as the FCC’s probe of the CBS 60 Minutes interview, as well as local defamation cases.

While Trump has no direct say in which cases the Supreme Court justices choose to take up, Carson Holloway, a political science professor at the University of Nebraska, said the president’s influence over libel law is not insignificant. He said that outside of the possibility of Trump’s personal defamation lawsuits escalating to the high court, Trump’s DOJ could decide to intervene in libel cases with amicus briefs.

“I think usually it gets the court’s attention if the Justice Department or the administration weighs in on something, even though they’re not narrowly parties to it,” Holloway told the Washington Examiner.

While Congress is limited in what it can do to address the actual malice standard, Trump showed his sway over the legislative branch in November when he solidified the death of the PRESS Act, which would have shielded journalists from subpoenas for their sources.

“REPUBLICANS MUST KILL THIS BILL!” Trump wrote on Truth Social of the legislation, which the House passed unanimously last year. He gave no explanation for the demand, the bill never made it through the Senate.

What does the Wynn rejection mean?

Last month, the Supreme Court declined to take up casino mogul Steve Wynn’s defamation case stemming from a lawsuit he brought against the Associated Press in 2018, shooting down the lone chance the high court had to address libel law in the coming year.

Without any sign of dissent, the reason for the move was unclear, but Shu offered some possible scenarios.

“The Supreme Court only takes 90-some cases a year,” Shu said. “It could mean that they simply couldn’t take it, logistically.”

He also said “some years the Supreme Court docket seems to have themes, so it could be that this was not the year that was destined to cover First Amendment or libel cases.”

SUPREME COURT DECLINES TO REVISIT DEFAMATION RULE CRITICIZED BY TRUMP

London said it could suggest there are not more than two votes of support on the court for reexamining libel, when four are needed for the high court to take up a case. But he cautioned that could change, pointing to numerous abortion cases that preceded the landmark Dobbs ruling that overturned Roe v. Wade.

“It can take a long time to get the Supreme Court to change its jurisprudence,” London said.