Fed up with the red tape or troubled by their country's trajectory, one in four American expatriates are either planning to renounce their citizenship or seriously considering it.

According to a survey of more than 3,200 expats in 121 countries commissioned by Greenback Expat Services:

-

6% of expats are making plans to renounce their citizenship

-

20% are seriously considering it

-

42% wouldn't rule it out

-

32% say they'd never consider it

For those considering renunciation, the top reason for doing so—expressed by 40%—is a feeling that U.S. tax and account reporting requirements are too burdensome. Fifteen percent say they're concerned about the current political climate; 10% say they're disappointed in the direction of the U.S. government; 12% have married a non-U.S. citizen.

There are only two countries on Earth that tax people based on citizenship rather than where they live: the United States and Eritrea. That means most U.S. expats have to file income tax returns with two countries. While the American tax code has some provisions to reduce double taxation, expats still have to file and 30% say they owed taxes last year.

Aggravation with that approach is rising: 57% of expats say citizenship-based taxation should be repealed, a 10% increase over the 2021 survey.

There's much more to the red tape than filing multiple tax returns. Expats also have to contend with two laws that compel additional financial reporting:

The Bank Secrecy Act. This law's Foreign Bank Account Reporting (FBAR) provision requires Americans to annually report foreign financial accounts, including bank accounts, mutual funds and brokerage accounts. It's triggered if the total value of foreign accounts reaches $10,000 at any point in the year.

The Foreign Account Tax Compliance Act. FATCA is similar to FBAR, but it has much higher account-balance-triggers—in the hundreds of thousands. It's also more complex. Forty-one percent of surveyed expats said they're required to file under FATCA.

Some expats only have to file under FBAR; others, under FATCA. Some have to file under both. Each has its own form, and they go to two different entities. FBAR reporting is done via Financial Crimes Enforcement Network (FinCEN) Form 114. FATCA requires sending IRS Form 8938 along with your income tax return.

Either way, rather than simply disclosing the values on a certain date, expats have to figure out the maximum balance over the whole year for each of the accounts. Since the reporting thresholds are expressed in U.S. dollars, that means doing conversion calculations to see if you need to file. If you blow the math, you face a stiff $14,489 penalty—and that's if it's deemed an "unwilling" error. Otherwise, the penalty is the greater of $129,210 or 50% of the balance of your account.

Importantly, FATCA creates reporting burdens not only for expats but foreign financial institutions too. For that reason, many foreign banks refuse to serve Americans. That creates headaches of another kind.

Renouncing isn't free either: It costs $2,350, and if you're considered a "covered expat"—which is triggered by, among other things, having a net worth north of $2 million—you're subject to an exit tax.

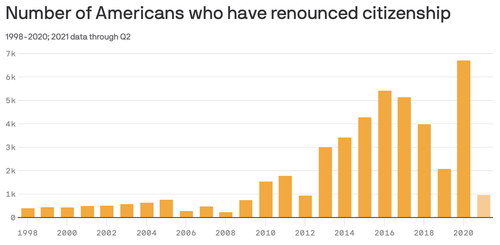

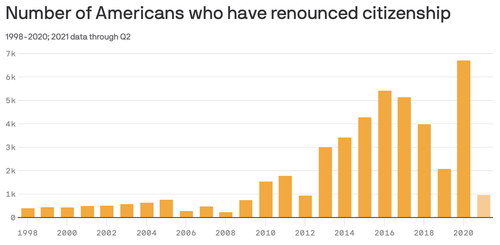

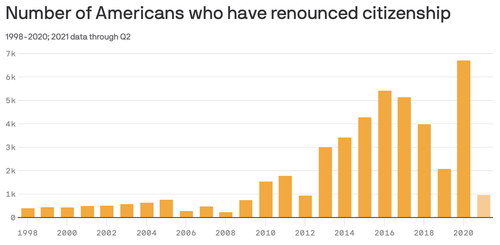

The record for citizenship renunciations came in 2020, when 6,705 Americans called it quits. In 2021, the number plummeted to 2,426. It's not that expats were falling back in love with the empire: The empire effectively blocked the exits. Giving up citizenship requires a face-to-face meeting and U.S. embassies and consulates generally declared such meetings were too dangerous while Covid-19 was circulating.

Just as divorces go into the public record, so do citizenship renunciations. Each quarter, the IRS posts the names of every person who's renounced their citizenship.

The Greenback Expat Services survey found 33% of expats are living abroad because of a significant other; 28% attribute it to a job relocation, and another 16% are there for the adventure or love of travel. Just 10% are certain they want to return to the United States permanently; 41% are unsure and 49% don't plan to.

Fed up with the red tape or troubled by their country’s trajectory, one in four American expatriates are either planning to renounce their citizenship or seriously considering it.

According to a survey of more than 3,200 expats in 121 countries commissioned by Greenback Expat Services:

-

6% of expats are making plans to renounce their citizenship

-

20% are seriously considering it

-

42% wouldn’t rule it out

-

32% say they’d never consider it

For those considering renunciation, the top reason for doing so—expressed by 40%—is a feeling that U.S. tax and account reporting requirements are too burdensome. Fifteen percent say they’re concerned about the current political climate; 10% say they’re disappointed in the direction of the U.S. government; 12% have married a non-U.S. citizen.

There are only two countries on Earth that tax people based on citizenship rather than where they live: the United States and Eritrea. That means most U.S. expats have to file income tax returns with two countries. While the American tax code has some provisions to reduce double taxation, expats still have to file and 30% say they owed taxes last year.

Aggravation with that approach is rising: 57% of expats say citizenship-based taxation should be repealed, a 10% increase over the 2021 survey.

There’s much more to the red tape than filing multiple tax returns. Expats also have to contend with two laws that compel additional financial reporting:

The Bank Secrecy Act. This law’s Foreign Bank Account Reporting (FBAR) provision requires Americans to annually report foreign financial accounts, including bank accounts, mutual funds and brokerage accounts. It’s triggered if the total value of foreign accounts reaches $10,000 at any point in the year.

The Foreign Account Tax Compliance Act. FATCA is similar to FBAR, but it has much higher account-balance-triggers—in the hundreds of thousands. It’s also more complex. Forty-one percent of surveyed expats said they’re required to file under FATCA.

Some expats only have to file under FBAR; others, under FATCA. Some have to file under both. Each has its own form, and they go to two different entities. FBAR reporting is done via Financial Crimes Enforcement Network (FinCEN) Form 114. FATCA requires sending IRS Form 8938 along with your income tax return.

Either way, rather than simply disclosing the values on a certain date, expats have to figure out the maximum balance over the whole year for each of the accounts. Since the reporting thresholds are expressed in U.S. dollars, that means doing conversion calculations to see if you need to file. If you blow the math, you face a stiff $14,489 penalty—and that’s if it’s deemed an “unwilling” error. Otherwise, the penalty is the greater of $129,210 or 50% of the balance of your account.

Importantly, FATCA creates reporting burdens not only for expats but foreign financial institutions too. For that reason, many foreign banks refuse to serve Americans. That creates headaches of another kind.

Renouncing isn’t free either: It costs $2,350, and if you’re considered a “covered expat”—which is triggered by, among other things, having a net worth north of $2 million—you’re subject to an exit tax.

The record for citizenship renunciations came in 2020, when 6,705 Americans called it quits. In 2021, the number plummeted to 2,426. It’s not that expats were falling back in love with the empire: The empire effectively blocked the exits. Giving up citizenship requires a face-to-face meeting and U.S. embassies and consulates generally declared such meetings were too dangerous while Covid-19 was circulating.

Just as divorces go into the public record, so do citizenship renunciations. Each quarter, the IRS posts the names of every person who’s renounced their citizenship.

The Greenback Expat Services survey found 33% of expats are living abroad because of a significant other; 28% attribute it to a job relocation, and another 16% are there for the adventure or love of travel. Just 10% are certain they want to return to the United States permanently; 41% are unsure and 49% don’t plan to.