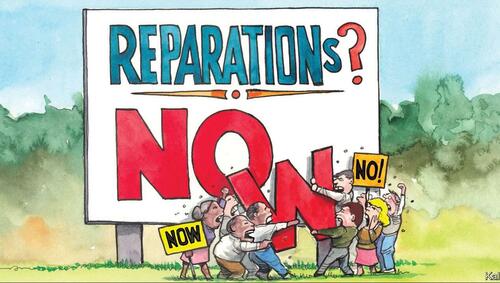

Below is my column in The Hill on the recommendations for reparations by two appointed bodies in California. After years of declaring this a moral imperative, the bill has come due for leaders like Gov. Gavin Newsom and San Francisco Mayor London Breed. The collective demand is for trillions in California alone with additional trillions demanded from Congress in a national reparations program. California Democrats will now have to render a decision on committing real money on reparations to show that this was not mere virtue signaling. That decision could be coming soon.

Here is the column:

A long-awaited meeting of San Francisco’s board of supervisors was set this week to discuss the recommendation of its African American Reparations Advisory Committee to give $5 million to each eligible Black resident as reparations. The meeting was postponed, but the city and the state soon must make a decision on a bill that has come due for Democratic politicians.

The city council voted unanimously to create the reparations committee in 2020. Even though California was a free state without slavery before the Civil War, the committee’s “particular focus has been the era of urban renewal, perhaps the most significant example of how the City and County of San Francisco as an institution played a role in undermining Black wealth and actively displacing the city’s Black population.” That could be viewed as only a partial payment for race-related injuries.

In the meantime, California Gov. Gavin Newsom (D) created his own Reparations Task Force, which just reached its own recommendations for $223,000 per person. Others have insisted the figure should be $350,000 for individuals and another $250,000 for Black-owned businesses. One California politician insisted the figure needs to be $800,000 per person, reflecting the average cost of a home in the state.

As these numbers rise, so do the calls for payments in both politics and the media. Even Disney has gotten into the act with a controversial children’s episode in which cartoon children demand reparations.

Notably, California’s law expressly states that this money should not be treated as compensation for federal reparations. That raises the question of whether a resident could receive $5 million from San Francisco, $223,000 from the state, and additional payments from the federal government.

Some congressional Democrats have pushed for similar federal reparations and passed a bill out of the House Judiciary Committee in 2021 that failed to receive a floor vote.

BET founder Robert Johnson has called for $14 trillion in federal reparations.

These reparations measures have a remarkable range of focus, from slavery to housing discrimination to wealth inequities. In California, there was a sharp disagreement on the purpose, with many advocates arguing that it was wrong to limit the money to descendants of slaves. Task force member Reggie Jones-Sawyer (D–Los Angeles) insisted that, “at the end of the day, people who are prejudiced against us are prejudiced against all of us.”

Ultimately, advocates like Jones-Sawyer lost a close vote on extending state reparations to all Black Americans. The state task force voted to limit it to descendants of slaves; there are almost 3 million potentially eligible Californians.

The two reparation bodies were tasked with calculating reparation awards — and both the city and the state will now be pressed to make good on their commitments.

The costs of such policies — condemned by critics as virtue-signaling — are being faced by some other jurisdictions as well.

For example, New York and numerous other cities have declared themselves to be “sanctuaries” for undocumented immigrants yet, in recent months, have protested increasing transfers of such immigrants to their jurisdiction.

The cost of California’s statewide reparations is estimated to be $569 billion. The state’s annual budget is roughly half that amount, at $268 billion.

Making things even more difficult, the state faces a $22.5 billion deficit and is seeking spending cuts to cover the shortfall.

This may not be a bill that can be politically postponed, given past statements by the governor and other Democratic politicians.

That leads to the question of such programs’ constitutionality. Even after the political approval of payments, it is not clear that this money will ever be paid.

Under the U.S. Constitution’s 14th Amendment, race-based classifications trigger strict scrutiny requiring a showing of both a “compelling state interest” and “narrowly tailored” means. In City of Richmond v. J.A. Croson Co., 488 U.S. 469 (1989), the Supreme Court struck down a set-aside for minority businesses due to a lack of evidence of specific injuries. The court ruled that general past discrimination was not enough and added that “the dream of a Nation of equal citizens in a society where race is irrelevant to personal opportunity and achievement would be lost in a mosaic of shifting preferences based on inherently unmeasurable claims of past wrongs.”

Then-Justice John Paul Stevens added his liberal voice against such programs, noting that Richmond’s law “encompasses persons who have never been in business in Richmond as well as minority contractors who may have been guilty of discriminating against members of other minority groups.”

The reparations given in 1988 to Japanese Americans who survived World War II internment camps posed an easier issue, since the recipients were directly injured by the government and the money was meant to compensate them for their injuries.

The decision to narrow programs like focusing on the descendants of slaves or on housing deprivations will certainly be better for constitutional review than a general reparations measure. However, even liberal scholars like Erwin Chemerinsky seem to concede that these reparation measures would face series legal headwinds in the courts. The likely legal challenges are not often considered in discussions of reparations — but they could create a highly combustible situation, if large reparations guarantees were suddenly negated.

That legal fight, however, must await a moment of truth for California legislators.

Democratic politicians have insisted for years that reparations are essential to address systemic racism. But politicians like Gov. Newsom now face demands to put their money where their mouths have been. The years of calls for reparations have created a greater expectation, even an urgency.

One well-known California activist declared:

“It’s a debt that’s owed, we worked for free. We’re not asking; we’re telling you.”

That expectation is reflected in recent polling, showing a massive shift in the Black community on the question: 77 percent of Black Americans now support reparations — but, overall, nearly seven-in-ten (68 percent) of all respondents oppose such payments.

Thus, after defining reparations as a moral obligation, politicians may find it difficult to say this is an inopportune moment.

For Newsom and for San Francisco’s Board of Supervisors, the bill is now due.

Below is my column in The Hill on the recommendations for reparations by two appointed bodies in California. After years of declaring this a moral imperative, the bill has come due for leaders like Gov. Gavin Newsom and San Francisco Mayor London Breed. The collective demand is for trillions in California alone with additional trillions demanded from Congress in a national reparations program. California Democrats will now have to render a decision on committing real money on reparations to show that this was not mere virtue signaling. That decision could be coming soon.

Here is the column:

A long-awaited meeting of San Francisco’s board of supervisors was set this week to discuss the recommendation of its African American Reparations Advisory Committee to give $5 million to each eligible Black resident as reparations. The meeting was postponed, but the city and the state soon must make a decision on a bill that has come due for Democratic politicians.

The city council voted unanimously to create the reparations committee in 2020. Even though California was a free state without slavery before the Civil War, the committee’s “particular focus has been the era of urban renewal, perhaps the most significant example of how the City and County of San Francisco as an institution played a role in undermining Black wealth and actively displacing the city’s Black population.” That could be viewed as only a partial payment for race-related injuries.

In the meantime, California Gov. Gavin Newsom (D) created his own Reparations Task Force, which just reached its own recommendations for $223,000 per person. Others have insisted the figure should be $350,000 for individuals and another $250,000 for Black-owned businesses. One California politician insisted the figure needs to be $800,000 per person, reflecting the average cost of a home in the state.

As these numbers rise, so do the calls for payments in both politics and the media. Even Disney has gotten into the act with a controversial children’s episode in which cartoon children demand reparations.

Notably, California’s law expressly states that this money should not be treated as compensation for federal reparations. That raises the question of whether a resident could receive $5 million from San Francisco, $223,000 from the state, and additional payments from the federal government.

Some congressional Democrats have pushed for similar federal reparations and passed a bill out of the House Judiciary Committee in 2021 that failed to receive a floor vote.

BET founder Robert Johnson has called for $14 trillion in federal reparations.

These reparations measures have a remarkable range of focus, from slavery to housing discrimination to wealth inequities. In California, there was a sharp disagreement on the purpose, with many advocates arguing that it was wrong to limit the money to descendants of slaves. Task force member Reggie Jones-Sawyer (D–Los Angeles) insisted that, “at the end of the day, people who are prejudiced against us are prejudiced against all of us.”

Ultimately, advocates like Jones-Sawyer lost a close vote on extending state reparations to all Black Americans. The state task force voted to limit it to descendants of slaves; there are almost 3 million potentially eligible Californians.

The two reparation bodies were tasked with calculating reparation awards — and both the city and the state will now be pressed to make good on their commitments.

The costs of such policies — condemned by critics as virtue-signaling — are being faced by some other jurisdictions as well.

For example, New York and numerous other cities have declared themselves to be “sanctuaries” for undocumented immigrants yet, in recent months, have protested increasing transfers of such immigrants to their jurisdiction.

The cost of California’s statewide reparations is estimated to be $569 billion. The state’s annual budget is roughly half that amount, at $268 billion.

Making things even more difficult, the state faces a $22.5 billion deficit and is seeking spending cuts to cover the shortfall.

This may not be a bill that can be politically postponed, given past statements by the governor and other Democratic politicians.

That leads to the question of such programs’ constitutionality. Even after the political approval of payments, it is not clear that this money will ever be paid.

Under the U.S. Constitution’s 14th Amendment, race-based classifications trigger strict scrutiny requiring a showing of both a “compelling state interest” and “narrowly tailored” means. In City of Richmond v. J.A. Croson Co., 488 U.S. 469 (1989), the Supreme Court struck down a set-aside for minority businesses due to a lack of evidence of specific injuries. The court ruled that general past discrimination was not enough and added that “the dream of a Nation of equal citizens in a society where race is irrelevant to personal opportunity and achievement would be lost in a mosaic of shifting preferences based on inherently unmeasurable claims of past wrongs.”

Then-Justice John Paul Stevens added his liberal voice against such programs, noting that Richmond’s law “encompasses persons who have never been in business in Richmond as well as minority contractors who may have been guilty of discriminating against members of other minority groups.”

The reparations given in 1988 to Japanese Americans who survived World War II internment camps posed an easier issue, since the recipients were directly injured by the government and the money was meant to compensate them for their injuries.

The decision to narrow programs like focusing on the descendants of slaves or on housing deprivations will certainly be better for constitutional review than a general reparations measure. However, even liberal scholars like Erwin Chemerinsky seem to concede that these reparation measures would face series legal headwinds in the courts. The likely legal challenges are not often considered in discussions of reparations — but they could create a highly combustible situation, if large reparations guarantees were suddenly negated.

That legal fight, however, must await a moment of truth for California legislators.

Democratic politicians have insisted for years that reparations are essential to address systemic racism. But politicians like Gov. Newsom now face demands to put their money where their mouths have been. The years of calls for reparations have created a greater expectation, even an urgency.

One well-known California activist declared:

“It’s a debt that’s owed, we worked for free. We’re not asking; we’re telling you.”

That expectation is reflected in recent polling, showing a massive shift in the Black community on the question: 77 percent of Black Americans now support reparations — but, overall, nearly seven-in-ten (68 percent) of all respondents oppose such payments.

Thus, after defining reparations as a moral obligation, politicians may find it difficult to say this is an inopportune moment.

For Newsom and for San Francisco’s Board of Supervisors, the bill is now due.

Loading…